For Tibetan poet Chen Metak (1970–2022), the relationship between writing and society is one of “blood and flesh, sword and arrow, father and son.” Considered one of Tibet’s most celebrated contemporary poets, Metak was born in Chentsa in 1970—his pen name literally means “Fire Spark of Chentsa”—and went on to graduate from Qinghai University. During his lifetime, he published a number of poetry books, including Clouds Flow Eastward and My Daughter Yuchung Dawa, and his poems are included in school curricula within Tibet.

According to writer and translator Bhuchung D. Sonam, Metak was dedicated to preserving Tibetan culture through his poetry and through his role as a middle school teacher. “Through his poems Chen Metak expressed the political and social messages of the society and demonstrated a strength of understanding, so that many Tibetan youths liked his works,” Sonam told Radio Free Asia after Metak’s death. As one way of continuing Metak’s legacy, Sonam has translated a number of his poems into English, including the five below. Read more of Metak’s poems in Burning the Sun’s Braids: New Poetry from Tibet, and then listen to Sonam discuss his translation practice on a recent episode of Tricycle Talks.

***

A Stranger

This is my guesthouse

Where I close my eyes for a day.

Stranger,

Please come in,

Sit on this chair,

Enjoy a cigarette.

I have a bottle of white wine

A plateful of sunflower seeds

Topped with two apples.

This is our small feast.

Please relax,

Why do you stand up?

I will never ask where you come from or

Where you are going.

Likewise,

I will not ask why suddenly you knocked at my door.

No interrogation here.

Ah, stranger

Drink your wine

Nibble on sunflower seeds,

Have an apple, and

Then you can leave.

After you go away,

Shutting the door tightly

I will have to cry—

For that person

Whose shadow the moon erased

Whose colour the rain washed away

Whose name the crow plucked out,

For people like me, and

For the ownerless who survive outside the door.

Without a sound

I have to cry once.

My Home

As soon as returning home

I entirely forget that this realm

Has neither sunlight nor sky.

How happy it is here

To open the doors and windows,

To close them at anytime

In freedom.

Though the realm

Makes loud noises

Outside these windows,

How happy it is here

To recline on the sofa-set,

To be able to relish this silence and warmth

At my will.

Half a Poem

Whenever I get free time

I write half a poem and

Store it in my bag.

A single poem cannot take me to the Pure Land

Nor can it drag me to hell.

A finished poem

Would be taken away by friends and strangers, and

To those who may like or dislike it.

An unfinished poem gives me

Pleasure and satisfaction, for now.

Impermanence

Snow that fell last night

Disappeared in the morning

Fog that engulfed the morning

Disappeared by noon

Rays of the sun that shone at noon

Disappeared in the evening

The woman I married ten years ago,

Where is she now?

Lhasa Diary

In a day, cold wind may blow,

A colourless and intangible wind

Rising through the openings in your stones,

On the walls of your house and iron fences,

Making hundreds of holes for spiders and scorpions to sneak in,

Fangs of darkness crowding in the dark holes will

Cut your sunrays into pieces,

Bringing the second black night

That even the lamps of your history cannot extinguish.

In a day, it may rain

Teardrop-like rain falling from your golden canopies

Hues of your white and red colours may turn

Into long bloody footprints left by scorpions,

Each imprint turning to a document,

Your emperors and princes will have

No stone pillars for their final testament, only elaborate tombs.

One day, from the walls of your water tombs

Yellow ducks will fly out in terror,

Singing you a skeleton-coloured poem

With a tiny little hole in it, and

Through this hole

You may be able to see once the world in which you live.

One day, a tongue of flame may shoot up from the crown of Iron Hill

The flame may hear the laments of your chained sunrays,

It may taste the sour air coming and going across the stone bridge,

Furthermore, it may feel the hunger of birds and fishes of Yarlung Tsangpo1,

It may see the sons and daughters of aristocrats decked in corals and turquoise.

One day, it is possible that I will see the white walls of Tsuglakhang

Hidden behind the garden of willow with its smooth walls,

It is possible that I will see the low terraces of the stone houses,

Seeing them I may have to follow your pointing finger to

A valley of history where the sunlight does not penetrate.

On a day like that

Silently I may call your name one more time.

Translator’s Note:

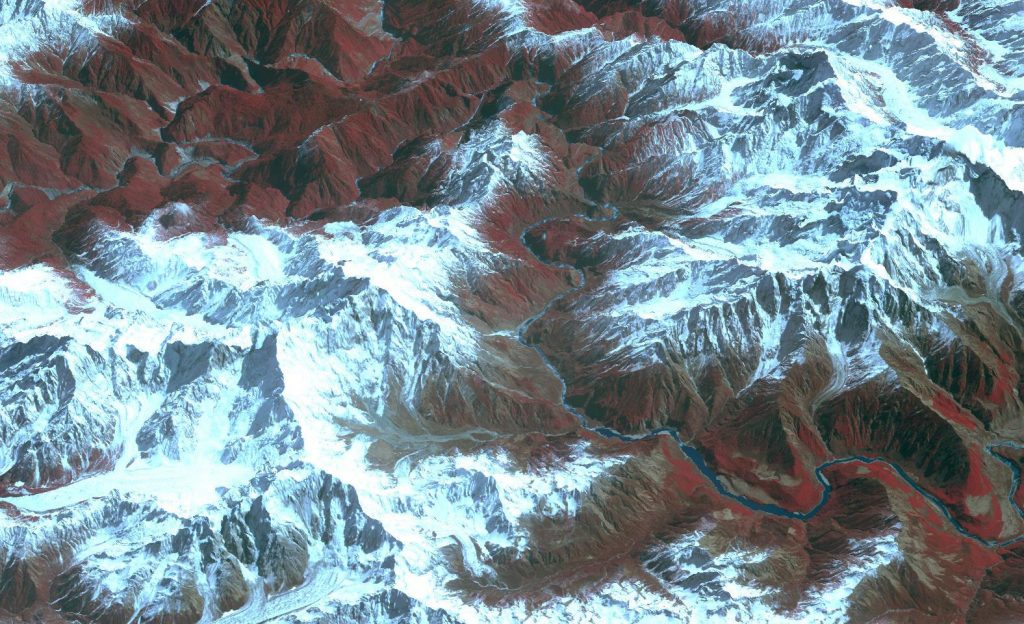

Yarlung Tsangpo (aka Tachok Khabab) is the highest major river in the world, rising from a glacier near Mt. Kailash in Western Tibet. The 2,900-kilometer-long river flows through the heartland of Tibet, including the Yarlung Valley, hence the name Yarlung Tsangpo. Yarlung Valley was the citadel of Tibetan civilization and Tibet’s capital from about 127 BCE to 630 CE. The river is a lifeline for Tibetans who farm along its banks. As it descends, the surrounding vegetation changes from cold desert to arid steppe to deciduous scrub vegetation and, ultimately, changes into a conifer and rhododendron forest. Sedimentary sandstone rocks found near Lhasa, Tibet’s capital city, contain grains of magnetic minerals that record the Earth’s alternating magnetic field current.

Yarlung Tsangpo flows in the world’s largest and deepest canyon, Yarlung Tsangpo Grand Canyon, which is more than twice the depth of Colorado’s Grand Canyon. It flows into India and Bangladesh to become the mighty Brahmaputra River forming The Ganges or Brahmaputra Delta, which is the agricultural heartland of India and Bangladesh. The river finally empties into the Bay of Bengal. Over half a century since its occupation, China has been damming Tibetan rivers, including the Yarlung Tsangpo. A mega Zangmu Hydropower Station was completed in 2015 on the main stream of Brahmaputra and plans are afoot for more dams. Such massive damming will have incalculable consequences for the plateau’s fragile ecosystem and threaten the livelihood of millions of people in riparian countries.

♦

Reprinted with permission of the translator.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.