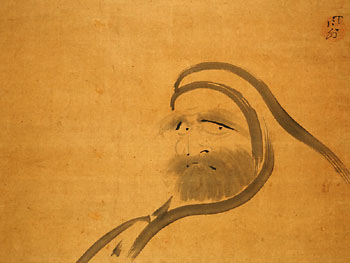

Revered as the father of Zen Buddhism, some scholars have still denied or raised doubts as to whether Bodhidharma actually existed.

He did. In fact, new evidence from Chinese scholarship suggests that he was a critically important historical figure, one far more fascinating than previously imagined. But if this is true, why doesn’t he appear in any official imperial records that were created while he lived?

The earliest and most reliable account we have concerning Bodhidharma’s life, written by the great monk-historian Dao Xuan around the year 650 AD, clearly suggests that Bodhidharma did not like emperors and made a point to avoid them. The famous story of Bodhidharma meeting and rejecting the “Bodhisattva Emperor Wu” of the Liang Dynasty is only the most famous bit of information that supports this thesis.

Dao Xuan wrote of Bodhidharma that his “followers were like a city,” and “everywhere he traveled people were enlightened.” But he also says that “Those [emperors and elites] who wanted him to come to them could not draw him near,” and he “avoided places of imperial sway.” This appears to explain why Bodhidharma does not appear in any official imperial records—he simply stayed away from emperors. Dao Xuan, however, a Buddhist historian who likely had direct contact with disciples of Bodhidharma’s main disciple Huike, does provide various accounts of Bodhidharma’s life and the lives of his two principal followers. This textual evidence, along with early stone monument records in China and various local records, argue conclusively that Bodhidharma was a real person, not someone made up later.

Dao Xuan wrote of Bodhidharma that his “followers were like a city,” and “everywhere he traveled people were enlightened.” But he also says that “Those [emperors and elites] who wanted him to come to them could not draw him near,” and he “avoided places of imperial sway.” This appears to explain why Bodhidharma does not appear in any official imperial records—he simply stayed away from emperors. Dao Xuan, however, a Buddhist historian who likely had direct contact with disciples of Bodhidharma’s main disciple Huike, does provide various accounts of Bodhidharma’s life and the lives of his two principal followers. This textual evidence, along with early stone monument records in China and various local records, argue conclusively that Bodhidharma was a real person, not someone made up later.

Bodhidharma wasn’t the only early Chinese Zen master who was a political rebel—his disciple Huike and others down through the lineage were as well. Indeed, anti-imperial sentiment is so prominent in old Chinese Zen texts that I’ve come to regard this as a defining aspect of early Zen. In the struggle between it and Imperial Buddhism, the emperors eventually gained the upper hand, making Zen a handmaiden of imperial power within a few hundred years of Bodhidharma’s life. But Zen didn’t go down without a fight!

Bodhidharma’s disciples Huike and Sengfu continued his rebellious ways, both actively avoiding emperors. Sengfu lived within walking distance of Emperor Wu’s court for decades, but never responded to entreaties to come teach there. Other evidence indicates that Huike riled the religious establishment of his day by preaching Bodhidharma’s Zen to commoners, undermining the imperially sanctioned Buddhist schools. The traditional story says authorities executed Huike when the Imperial Buddhist religious establishment could no longer tolerate his defiance of their teachings and authority. While the texts that tell this tale are not as reliable as Dao Xuan’s stories, they concur with other evidence that remains.

—Andy Ferguson

This post is part of author and scholar Andy Ferguson’s new “Consider the Source” series. As an old Chinese saying goes, “When drinking water, consider the source.” In the coming weeks, Ferguson will ask and answer seemingly simple (but in the end, profound) questions about the “source” of East Asian Buddhism, weaving a tale of both spiritual inspiration and political intrigue.

This fall, Tricycle will be traveling to the source itself, China, in a special pilgrimage led by Ferguson and abbot of the Village Zendo Roshi Pat Enkyo O’Hara. Want to come with us? Click here for more information.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.