When meditators’ minds have reached genuine happiness in the dhamma through their mindfulness and discernment, clearly seeing the four noble truths, none of them—not one—will revert to looking for happiness in the world or in material things. That’s because happiness in the dhamma is a lasting happiness: solid, refined, and genuinely pure. If you compare worldly happiness with the happiness of the dhamma, you’ll see that there’s not even the least real happiness to it. It offers nothing but stress, nothing but drawbacks. So why do we think it’s happiness? Because we’re burning with pain. We look to worldly happiness and pleasures to relieve the pain, which then goes away for a while but then comes back again.

For instance, the Buddha said that birth is stress, but ordinary people regard it as something happy. We don’t see the stress and pain involved. Yet once the mind has reached the happiness of the dhamma, it can see that birth is really stressful, just as the Buddha said. The reason we have to look after ourselves, take care of ourselves, and still can’t find any peace, is because these things that have been born come to disturb us. We sit down and get some pleasure and ease from sitting down, but after a while it becomes painful. We say that it’s pleasant to lie down, but that’s true only at the very beginning. After we’ve lain down for a long time, it begins to get unpleasant. So we have to keep changing postures in order to gain pleasure. We look for this thing or that, but as soon as we’ve gained just a little pleasure from them, stress and pain come in their wake. If we have a family and home to live pleasantly together, there are only little pleasures, which have us fooled and deceived, while there are hundreds and thousands of unpleasant things. The happiness and pleasure that come from external things, material things, is never enough. It keeps wearing away, wearing away, and wearing us out, to no purpose at all. This is why those who have reached the dhamma don’t return to this world so filled with sorrows and turmoil.

And this is why I want you to put an effort into meditating, contemplating in line with the dhamma. Even if you aren’t yet convinced of the dhamma, at least take the teachings of the Buddha as your working principles. For example, when the Buddha teaches about the three characteristics of inconstancy, stress, and not-self, we should train our minds to see in line with what he said. Give him a try. For example, he says that this body of ours is filled with all sorts of unclean things. We may not agree, but at least give it a try to see what happens when you look at things in line with what he says. He says it’s not clean. Atthi imasmim kaye—in this body there is: hair of the head, and it’s not clean; hair of the body, and it’s unclean; nails, and they’re not clean. Don’t be in a hurry to reject the Buddha’s teachings. Take a look to see whether these things really are unclean or not. When the mind focuses on these things more and more steadily, and begins to feel quiet and at ease, the truth of these things will gradually appear more and more clearly. Conviction in the dhamma, in the practice, will arise. Energy will arise as we want to see more. As this awareness grows greater, the mind will grow more luminous and still. This is the way of the practice. When you go back home, remember this simple principle: practice meditation by observing your body, observing your mind.

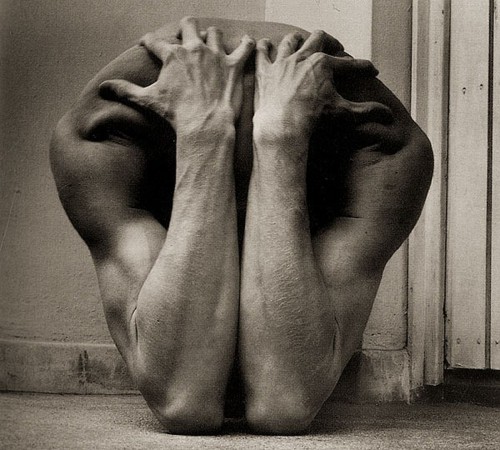

Use your mindfulness to keep track of the body in and of itself, so as to know it in line with its truth. If you don’t look at the body, then look at the mind in and of itself. When you observe the movements of the body and mind, the pleasures and pains that arise so often, you’ll develop awareness and skill. You’ll learn how to handle things in line with the Buddha’s teachings. You’ll gain the discernment that sees and knows the truth. You’ll see things more and more clearly. The more clearly you see things, the stronger and more quiet the mind will grow. You’ll see the body as stressful and unclean, but you’ll have to look after the mind, keeping yourself wise to the fact that the stress and uncleanliness are an affair of the body, not of the mind.

The body has been unclean all along. We’ve lived with it all this time, so there’s no need to be afraid of seeing these things, no need to reject them. We should contemplate the body so as to give rise to a sense of chastened dispassion. When you let go of the body, let go in a discerning way. Don’t let go in a way in which delusion and misunderstanding overcome the mind. Don’t get disgusted with the body so that the mind becomes restless and agitated and stops meditating. That kind of dislike is wrong. When we look at things we don’t like—such as the inconstancy, the stressfulness, and the unattractiveness of the body—remember that they’re part of the noble truths. The Buddha said that they’re very beneficial.

Contemplating the unattractiveness of the body is very beneficial because it serves an important purpose. If we see the body properly in this way, it helps the mind grow still with a sense of disenchantment. And that’s what will cure our delusions and misunderstandings. This is why, when ordaining a monk, the very first step is to teach him the five meditation themes—kesa, hair of the head; loma, hair of the body; nakha, nails; danta, teeth; taco, skin—as a way of developing discernment and knowledge of the truth.

So hold on to these themes and keep contemplating them, regardless of whether the mind is still or not. Whenever you have any free time, contemplate them. You can contemplate them even while you’re working. Contemplate them until you get down to the minute details in a way that gives rise to a sense of stillness and ease.

It’s similar to when we do physical work. We get wages for each hour we work. The more hours we work, the higher our pay. But if you get greedy and keep working without rest, then the body wears out, the mind grows weak, and you can’t work any more. So you have to rest and eat to regain the strength of your body and nerves. Even though you don’t get paid for the time you rest, you’re willing to take the loss for the sake of your strength of body and mind, so that you can contend with the work after you’ve rested.

It’s the same when you meditate: if you just keep contemplating and investigating, it won’t be long before the mind gets restless and agitated. So you have to bring the mind to stillness to avoid its getting restless. If it gets restless, it’ll have no peace. It’ll get all tied up in knots and will grow weary of the meditation. So contemplate for a while until you can sense that the mind wants to stop and rest; then focus back on the in-and-out breath or anything else that will serve as a gathering point for the mind. Gradually let go of your contemplation, gradually let the mind settle down, so as to gain strength from the sense of pleasure and ease that come in this way. Don’t worry about how long you should stay there. Even though the mind doesn’t seem to be gaining any knowledge, don’t worry about it. It’s as when you’re resting from physical labor: even though your boss doesn’t give you anything for the hour you rest, you’re willing for the sake of gaining energy—in this case, strength of mind.

This is why the noble disciples constantly practice concentration, constantly get the mind to settle down. After they’ve contemplated to the point where the mind gets weary, they let the mind grow still. After it’s had enough stillness, they go back to their contemplation. This is how we should practice. If we practice in this way, the mind will gain energy and strength, will gain discernment to the end point of all suffering and stress, seeing things for what they actually are. The question asked the other day—how to practice when you go back home—was a very good question. The answer is: keep looking after your mind in the way I’ve described here. Practice exercising your own mindfulness and discernment.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.