As long as I can remember, I have felt a distance from the culture that has surrounded me. Try as I might, I could never reconcile the disparity between what I wanted out of my life and what was expected of me by my community in Lebanon, and around the Arab world at large. Having grown up spending time in many different locales across the Middle East—from Beirut to Baku to Amman and beyond—I had seen and experienced a pretty comprehensive overview of the wider area’s culture and mores. And yet, I still could never find a strong connection with my heritage and its spiritual and cultural aspirations. In an era of rapid Westernization under the guise of modernization, I couldn’t identify with the traditions being passed down and presented to me from Arab and Western sides alike.

In Lebanon, this can be hard. It’s expected of me—as it is expected of many of my peers—that I side with the talking points laid out by my community’s designated leaders. Among the country’s Christian communities—which includes my own family’s Greek Orthodox sect, which tends to lean left-wing, and the Maronite Catholics, who make up the overwhelming majority of Christians in Lebanon and tend to lean more right-wing—even those who are not supporters of American foreign policy have to constantly reaffirm their allegiance to the sovereignty of the Lebanese state and the wider Arab community as a whole. And yet, it’s become impossible for me to ignore the prejudices intrinsically intertwined within Lebanon’s sociopolitical and cultural stances. Racial and religious minorities, as well as members of the LGBTQIA+ community, are regularly demonized for no other reason than to play on fears and bigoted views passed down as traditions. It’s not uncommon to see families trying to break up relationships, and sometimes even friendships, over sectarian differences.

In a sense, we’ve been preparing for Buddhism our entire lives.

It’s also not uncommon now for those growing up in Lebanon to seek out alternative paths to those that have been laid out for them, ones that do not indulge in the cynical excesses of the West or the cyclical blunders of the region. Considering the region’s scarce interaction with East Asia in the past, it seems strange that Lebanese youth would look toward it for guidance when the Middle East is considered the center of the world’s major monotheistic institutions. However, the significant emphasis placed on our spirituality makes it an essential component of our well-being, and so, in a sense, we’ve been preparing for Buddhism our entire lives.

Like many Middle Eastern and Western seekers of my generation, tenets of Eastern philosophy and spirituality first came onto my radar through the more inspired storytelling of the fantasy and science fiction genres, from children’s entertainment like Avatar: The Last Airbender to popular film franchises like Star Wars. But, along with the rise in popularity of mindfulness, meditation, yoga, and martial arts as a form of balance and self-care, it was the global otaku community’s direct exposure to the manga and anime of the time—with franchises such as One Piece and Dragon Ball—that really encouraged those of us in university who were intrigued by Eastern cultures to explore the religions that inspired it all.

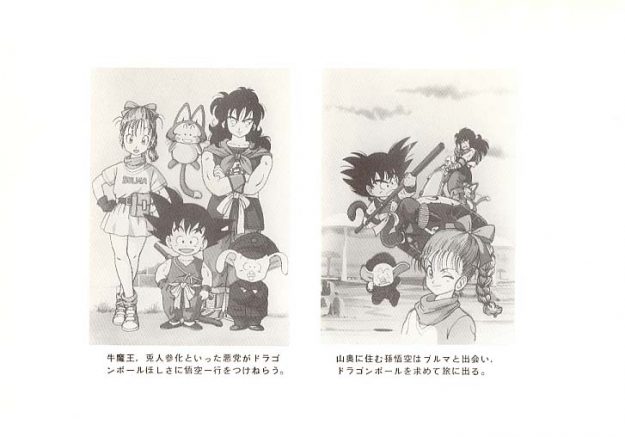

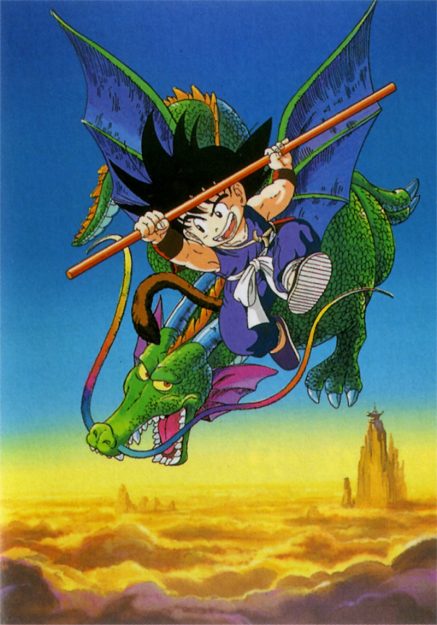

In particular, there was something so universal about Dragon Ball that connected with Arab youth, torn between a local tradition that no longer represented their values and the push of Westernization that demanded they embrace modernization. Set in a fictional world based on Asia, the world of Dragon Ball took inspiration from many different cultures from across the continent, including elements from Japan, China, South Asia, Central Asia, the Arab world, and Indonesia, all through a distinctly Buddhist milieu. Artist and creator Akira Toriyama even initially modeled Dragon Ball after a combination of Journey to the West—a 16th-century Chinese text read as an extended Buddhist allegory—and the Nanso Satomi Hakkenden—a Japanese epic of gesaku literature following the adventures and mishaps of eight warriors from Kanto on a quest to collect eight Buddhist prayer beads—which Toriyama adapted into the collecting of the seven titular dragon balls. It is precisely this cultural bridgemaking and world-building that set Dragon Ball apart from its competitors.

While other anime juggernauts, like the hugely popular Pokémon, Digimon, and Yu-Gi-Oh! franchises, had wider viewerships in the West, they did not offer as much insofar as a distinctively pan-Asian narrative. It’s no surprise that the first animated adaptation of Dragon Ball, which covered roughly the first half of the manga where its cultural and literary inspirations were its primary focus, was more popular in the Arab world than in the West, where its fighting-oriented sequel Dragon Ball Z blossomed, kicking off the massive anime boom of the early aughts. Not only was Dragon Ball integral in the socioethical development of a generation of children from all over the Arab world, its palpable influence on the shonen anime and manga of the aughts—franchises like Naruto and Bleach, which were all the rage in the Middle East at the time—meant that its distinct philosophy was even felt by fans who had never even bothered to watch the original Dragon Ball to begin with.

Along with the renewed interest in Journey to the West and the Nanso Satomi Hakkenden, Toriyama’s innovative storytelling also inspired a new culture and generation to seek out other canonical East Asian philosophical texts. Classics such as the Tao Te Ching and The Platform Sutra of the Sixth Patriarch were passed to eager university students searching for knowledge that appealed to the distinct sensibilities developed in a globalized world. Our elders—who were both hostile to and envious of the West—feigned immediate repulsion to our burgeoning interests in the cultures of East Asia and its way of life. Yet, to us, it offered something new, something different from the paths that Arabization and Westernization had forced upon us.

Inspired by the secular Buddhist movement that was popular in the local alternative scene, it is here that I started to explore different texts revered by the Soto Zen School, in which much of secular Buddhist philosophy was rooted. Other than its palpable presence in Japanese media—which I had grown to cherish—what drew me to Soto Zen was its historical ties to the proletariat (to the extent that it used to be referred to derogatorily as “farmer Zen”) and its dispelling of the ritual and dogmatism that alienated many from more local religions. Considering my profound discomfort with the polarized mentality of my peers, I found comfort in the concept of nonattachment, in particular, which is a central principle of Zen Buddhism. A technical Chan term for nonattachment is “wú niàn” (i.e., “nothought”), which can be conceived of as an “unstained” state. Nonattachment is thus a form of not identifying with one’s thoughts—a separation to avoid further harm from them. For it is our attachment to the transient world around us, of which we, as luminous minds, have no control, that provokes passionate emotions such as fear or anger that lead to our existential suffering. In the words of Lao Tzu, as written in the Tao Te Ching, this is best exemplified in the passage:

“Fame or Self: Which matters more?

Self or Wealth: Which is more precious?

Gain or Loss: Which is more painful?

He who is attached to things will suffer much.

He who saves will suffer heavy loss.

A contented man is rarely disappointed.

He who knows when to stop does not find himself in trouble.

He will stay forever safe.”

Even when removed from the drama that comes with political participation, our social lives are intrinsically tied to such frivolous pursuits. It is this attachment that is at the heart of every Lebanese crisis. It is the determinant of our social standing. Your community will judge you for having none of it; they will spur you on to pursue them as a means and end. And so, we are forced to pursue such frivolities, accumulating worthless status symbols—always spending, always saving, always suffering, never stopping—until an inevitable burnout. In a climate as overwhelming as the Middle East, nonattachment is not merely a means of psychological fulfillment but also a coping mechanism necessary for survival.

Years have passed since I was first introduced to Zen in the alternative scene. Friends I made there have all gone their separate ways and now lead lives in the high-stress corporate hustles they were once loath to imagine themselves in. Giving in to their material attachments, I see them suffering the very personal crises they looked down upon back in university when they were willing to abandon their everyday concerns and live in the moment. I now see the wisdom of the Platform Sutra when Huineng insists that nonattachment is the only way to silence the noise that threatens to tear you down and turn you into that which you were told to hate and fear:

“Therefore, nothought is established as a doctrine. Because man in his delusion has thoughts in relation to his environment, heterodox ideas stemming from these thoughts arise, and passions and false views are produced from them.”

Though nonattachment is one path to leading a fulfilling life in the Middle East, it does not come so easily. In a culture as materialistic as Lebanon’s, it’s hard to forgo material comforts, let alone the immaterial comforts like honoring one’s ancestors, duty to one’s nation, and loyalty to a community’s cause. Regional political and economic spheres are so tied to sociocultural life that you can be psychologically dragged back into the commotions of Lebanese life without realizing that no one is forcing it on you and that, within your means, is a choice on how to proceed forward. As Huineng clarifies, it’s as simple as tuning it all out, one thought at a time:

“Successive thoughts do not stop; prior thoughts, present thoughts, and future thoughts follow one after the other without cessation. If one instant of thought is cut off, the dharma body separates from the physical body, and in the midst of successive thoughts, there will be no place for attachment to anything. If one instant of thought clings, then successive thoughts cling; this is known as being fettered. If, in all things, successive thoughts do not cling, then you are unfettered. Therefore, nonabiding is made the basis.”

It may seem difficult at first, impossible even. However, as conflicts drag on in the Middle East with no end in sight, the tolls on us, psychologically and physically, mean that our need to embrace nonattachment is made cogent and conclusive. As soon as I came to terms with this truth, I was finally able to accept it as a working theory. Away from the senseless passions and pains that have brought me nothing but strife, I finally found solace in the state of nonattachment. Only once we’ve firmly and resolutely “let go”—from accumulating material wealth, from participating in religious dogma, from seeing my fellow man as “the other”— can we finally lead the life we’ve always wanted for ourselves. In a sense, through embracing nonattachment and living its truth—as the Platform Sutra puts it—we can truly be reborn and start anew.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.