Editor-at-Large Andrew Cooper stopped by for a visit yesterday—quite a change from the Pacific Northwest, where he lives. The heat and rain are very familiar to him, though. He hails from the New York metro area. Still, he may miss the cool breezes off Puget Sound. Andy, web editor Phil Ryan and I got to talking (Phil was not distracted by the Shady Buddha during this meeting), and Phil noted that every time we use the term “Western Buddhism”—or even just “the West”—some people object. These comments have been helpful, forcing us to examine our use of the term. Andy suggested we look at a passage from Rick Fields’s How the Swans Came to the Lake, a wonderful book which, as its subtitle says, is “a narrative history of Buddhism in America.” Like contributing editor Katy Butler, whose interview with Jeff Bridges will appear in the August issue, Fields was a pioneer in Buddhist journalism. He was also involved in discussions that led to the founding of Tricycle and helped articulate its direction. In Swans, Fields has this to say about “East” and “West”:

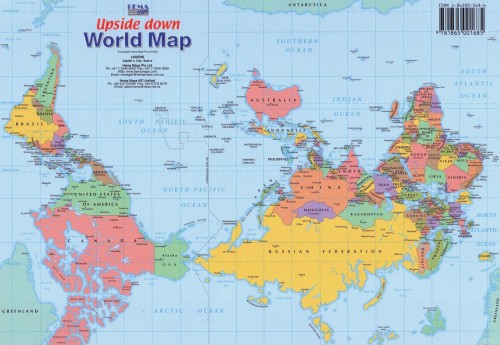

East and West are, after all, little more than shifting designations on a round earth, depending more on where one stands than on any absolute point through which the sun sets or rises.

Fields nonetheless describes a “Central Region,” stretching from India to the Mediterranean, where influences from both “East” and “West” meet in a rich cultural mix. By implication, East and West are to the right and left of the Center delineated by Fields, and while no more exact than any category or term, they nonetheless have their uses. Andy remembered writing an article—way, way back in 1993—for the Buddhist Peace Fellowship’s publication, Turning Wheel. It was his intention to open up the question of race in the Buddhist sanghas. You can read the full article here, but germane to this discussion is the following passage:

The idea of race is a good example of an ideological category. As Ashley Montagu argued years ago in Man’s Most Dangerous Myth: The Fallacy of Race, the very way we understand race—as a biological designation—is a “modern discovery,” a historical construct that developed in the eighteenth century as a way of justifying the slave trade. The notion of race comes to us laden with the history of white supremacism. When we take up the term, accepting its validity and forgetful of its historical production, that history exerts its power to shape our very perceptions. The starting point is already poisoned. We might have to use the term, but we don’t have to take it for granted. The understanding that conceptual designations shape perception is, of course, a familiar one to students of Buddhism. But Buddhist analysis tends to focus on the ultimate emptiness of all concepts, and remains naïve about the historical forces that lead to the production of particular ones. But to forget this historical dimension is to be shaped by it.

If we deny designations like “East” and “West,” we’d have to accept that no word or turn of phrase can withstand the scrutiny of rigorous interrogation. Whether we’re reading Derrida or Nagarjuna, we’ll probably conclude that every concept is ultimately empty but this does not mean we can’t have a conversation, something we couldn’t have otherwise.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.