As he was leaving San Francisco’s de Young Museum, the venue of “Rituals of Care,” his first West Coast career-spanning retrospective—on view through July 7—the artist Lee Mingwei was stopped by a woman. She told Mingwei that, prompted by The Letter Writing Project—one of the seven main installations that make up “Rituals”—she had been inspired to write to someone whom she had been putting off writing for years. A few steps later, a man who worked at the museum called out, “Are you Lee Mingwei? I love your work—it’s so powerful.”

Mingwei seems to elicit this kind of emotional reaction often. This was evident when I spoke with “Rituals” cocurator Janna Keegan as well as Rachel Sample, the director of the Minnesota Street Project Foundation. Sample’s foundation houses Mingwei’s piece Chaque souffle une danse (Each Breath a Dance)—on view April 5 through May 5, with a film presentation at the de Young April 9 through July 7. Sample says she has long admired his work, calling him “an incredibly special person [as well as] an incredibly special artist.”

Mingwei can’t help but notice the graciousness of the air at the de Young. He recounts a story about a cafeteria worker who gestured to him when he was waiting in a long line, allowing him to come to the front. “That’s you, though,” Keegan interjects. “Everyone loves you. You’re an incredibly generous person to work with.”

In many ways, this exhibition is like a coming home for Mingwei, as he’s known of de Young since 1993, when he went to school in nearby Oakland, at the California College of the Arts (CCA), back when it was still called the California School of Arts and Crafts. Mingwei maintains that he first thought about making the kind of art he currently creates while studying textiles and architecture at CCA.

“Deep down inside, I am still a textile artist just because I create human warp and weft—a relationship.”

“I was a weaver for many years, and even now, when people ask me, ‘Are you still a textile artist?’ I say, ‘Well, deep down inside, I am still a textile artist just because I create human warp and weft—a relationship.’ Not in the physical way, but in a societal way.”

His mentors at CCA include Suzanne Lacy, an artist known for her socially engaged and public performance art. She introduced him to her mentor, Allan Kaprow, who, in 1959, reimagined the role of art with his genre-defining interactive work 18 Happenings in 6 Parts. Transcending the idea of art as something meant to be hung on a wall or displayed on a pedestal, Kaprow divided a New York gallery into three makeshift rooms, with plastic sheeting, wherein he had people simultaneously paint lines and squares on a canvas, light matches, squeeze oranges, and play toy instruments. Mingwei says that the conversations he had with Lacy and Kaprow deeply affected and influenced the kind of artist he would become.

“Those are people who showed me this type of conceptual and social work that has a bigger resonance in society, compared to weaving a textile,” he says, laughing. “My textiles weren’t very good. They looked like terrible tablecloths, table runners, or doormats. They really were not very good.”

In graduate school at Yale, Mingwei met other people who would prove important to his practice, conceptual artists such as Roni Horn and Ann Hamilton, who taught him about participatory work as well as to listen and to be humble.

Yet before he went to art school or thought about a career in art, he was influenced by a different kind of teacher: a monk he studied with at a Ch’an (Chan) monastery in Taiwan in the summers when he was a boy.

“It was almost like spending time with Roni. We just walked in the woods, picking up little flowers or rocks that were left there, and coming back, cleaning the temple, and not reading at all about sutras,” Mingwei says. “There was nothing about what Buddha says you should do, [it was] more about cleaning the temple, going to bed when the sun sets, waking up when the sun rises, and meditating.”

Mingwei watched a lot of American TV growing up in Taiwan, and he particularly liked seeing the strong women on Charlie’s Angels fighting crimes. Yet, during boyhood summers, this all faded away. The monastery had no electricity, so he couldn’t keep up with his shows, but Mingwei reflects that even at 6 years old, he was quite the chatterbox, and as such talked excessively about Charlie’s Angels to his monk chaperone (who probably didn’t share his love of the trio).

Thinking back to that period, Mingwei relayed to me what he describes as a beautiful experience he had with this monk. One day, the monk asked him to come into his room and to sit across from him. He then pulled out an apple, handed it to the young Mingwei, and told him he had sixty minutes to describe it.

“Then he rang a bell, and I said, ‘Oh, it’s an apple, it’s red.’ But within thirty seconds, I’d run out of anything [more] I could say about this [apple]. And [the rest of the time] became the most difficult fifty-nine and a half minutes of my life, because I was so uncomfortable with not being able to say things,” Mingwei remembers. “At the end of this exercise, he gave me the apple and said, ‘Hold it and take a bite.’ So I held it, and the texture, and the aroma, and the juice—it all became so powerful, I started crying. It destroyed me, and really it was a moment of small enlightenment, I guess you could say.”

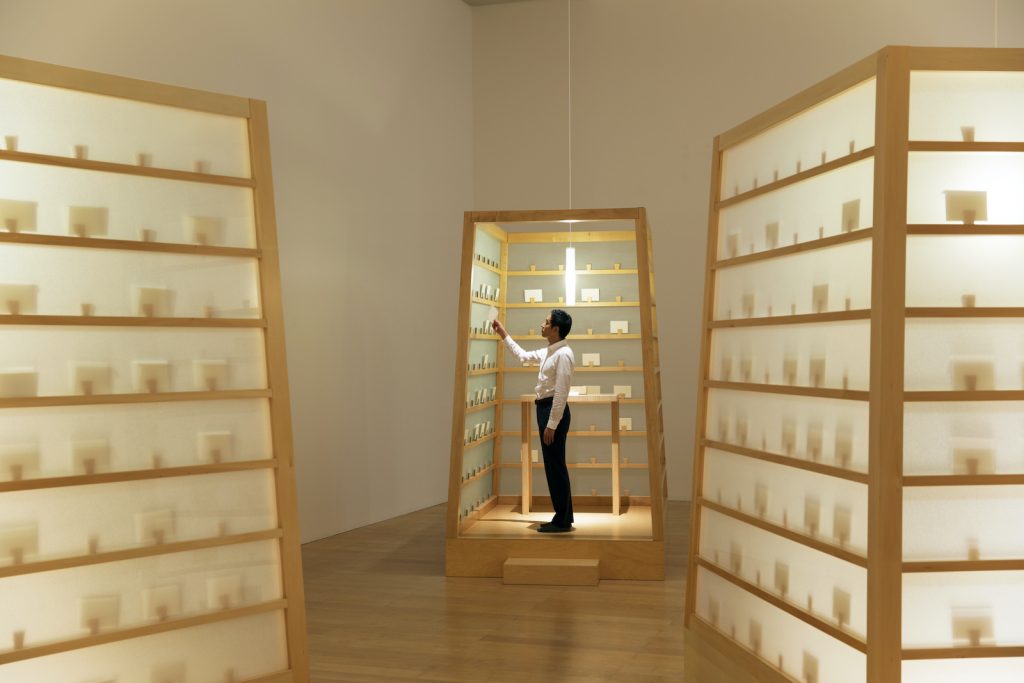

Along with The Letter Writing Project, where the artist invites participants to write out thoughts they had always meant to say but never did, other projects at the de Young include 100 Days with Lily, an exhibition of large prints documenting the life cycle of a flower. In both of these projects, Mingwei honors his grandmother, who was not a very approachable person, so he felt the need to communicate with her after her death. There’s also The Mending Project, where people bring in their clothes to be repaired while also giving them an opportunity to talk to the volunteer doing the mending, and Guernica in Sand, which recreates Picasso’s famous 1937 painting created after the bombing of civilians in Basque Country. As they would with a sand mandala, Mingwei and others create and then destroy the work, sweeping it into the center of the floor to make it a pile of sand once again.

With Our Peaceable Kingdom, Mingwei invites fourteen artists to copy Quaker minister Edward Hicks’s painting Peaceable Kingdom, which interprets a prophecy from the Book of Isaiah: “The wolf also shall dwell with the lamb, and the leopard shall lie down with the kid; and the calf and the young lion and the fatling together; and a little child shall lead them.” The people Mingwei invited in turn asked two more artists to rework the painting, so there are multiple copies exploring a vision of peace. There’s also Sonic Blossom, where a singer in the gallery invites a museumgoer to sit in a chair and offers to sing a Franz Schubert lied to them. This piece was inspired by Mingwei’s experiences playing the same lieder for his mother when she was recovering from heart surgery, the way she had played them for him when he was a little boy to help him to calm down.

During the pandemic, Mingwei says the breath and its potential hazards were on his mind. Then there was the harrowing video of the police officer Derek Chauvin killing George Floyd by kneeling on his neck, which ignited protests around the world against police brutality and white supremacy. So, thinking about inhaling and exhaling, Mingwei started an evening practice of deep breathing, followed by watching the sun set. While he watched, he made what he calls “breath drawings,” by exhaling to move drops of ink across alabaster slabs. For Chaque souffle une danse, sixty metal and wood candle stands are in a large circle, each paired with an accompanying drawing. A dancer enters, moving slowly, and lights a candle by each drawing. Once they are all lit, moving just as slowly, the dancer meticulously revisits each candle to extinguish the flame.

“I’m looking for the tension, and the tension is when someone comes in and blows out the candle or lights the candle, and that is where this whole thing became alive.”

Because of those flames, the performance couldn’t be at the de Young, so the museum partnered with the MSP Foundation to hold Chaque souffle une danse in its 20,000-square-foot gallery. Fortunately, Sample was more than enthusiastic about hosting the performance.

“I think he is capturing the emotional and psychological experience of so many during these moments of discord,” she says. “It contains both the depth of what he’s trying to translate, but also the experience of joy and delight of something that’s immersive and visceral.”

Throughout the forty-five-minute performance, the exhibition space will go between darkness and illumination. That juxtaposition was important to Mingwei, who says he saw the drawings against the sunset and the light coming through the alabaster as beautiful. That’s what made him think of the candles, but he wanted to push the work beyond being nice to look at.

“I realized if we had a candle, it would just look pretty,” he said. “I’m looking for the tension, and the tension is when someone comes in and blows out the candle or lights the candle, and that is where this whole thing became alive.” That’s the same reason he destroys the sand painting of Guernica, he says, and he thinks this comes from his Buddhist background.

“It’s like with koans,” he said. “It’s all about tension and balance, and that really is essential to all my work.”

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.