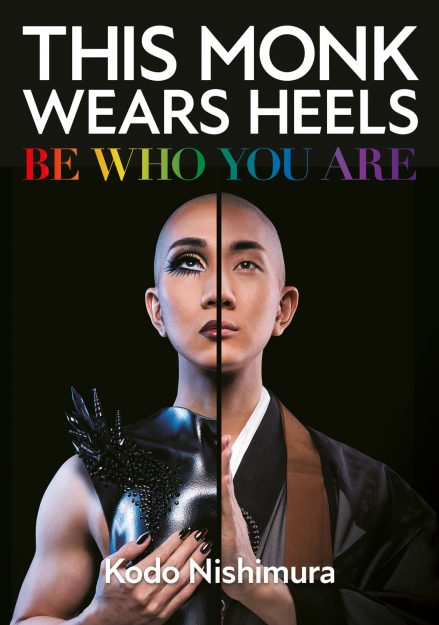

Kodo Nishimura is far from your typical Buddhist monk. He is also a makeup artist, LGBTQ activist, and, as of 2021, one of TIME’s Next Generation Leaders. Since being interviewed by Tricycle in 2017, Nishimura has been featured in many media outlets in Japan and abroad, including on Queer Eye: We’re in Japan! I recently translated his 2020 Japanese memoir into English as This Monk Wears Heels: Be Who You Are, to be published this February by Watkins Media in the UK and Penguin Random House in the US.

When I interviewed Nishimura on Zoom from his Tokyo home to discuss his memoir, he spoke frankly and poignantly, with the same powerful conviction I could sense while translating his writing. Central to his work is the belief that in Buddhism, as he puts it, “anybody and everybody can be equally liberated,” irrespective of sex, gender, race, or ability. Yet, he also told me how difficult his path to self-acceptance was. He has struggled to reconcile his authentic self—someone who identifies as neither male nor female—with the traditional expectations of how a Japanese monk should dress and act.

“It’s hard to be who I am,” he told me.

During his childhood in socially conservative Japan, Nishimura found refuge from homophobia and ostracization through studying English and connecting online with peers who were also exploring their gender identity and sexuality. While still attending high school, and despite initial opposition from his parents, he decided to leave Japan for the US. There, he studied English, art, and then makeup. And with the help of mentors and friends who were completely open about their gender identities and sexuality, he found the freedom to express who he truly was.

At the age of 24, Nishimura made another fateful decision—to return to Japan and train as a Buddhist monk like his father before him. As Nishimura recounts in his book, up to that point he had never intended to become a monk. He had even “fiercely disliked” Buddhism at one point in time, an attitude he describes as originating from “ignorance and prejudice.” “I needed to face my own Buddhist roots. . . something I had avoided for so long,” he writes.

Upon his return, Nishimura completed the arduous training to become a monk of the Pure Land school and stayed in Japan to help run his family’s temple in Tokyo. Today, in addition to writing and appearing frequently in media, he is active at the forefront of Japanese Buddhism’s diversity initiatives and gives many talks in Japan and overseas.

When you wrote your Japanese memoir, did you imagine English speakers also reading it? I know you added extra text to the English version, such as explanations of Buddhist teachings. I always intended my book to be for a global audience. However, the intentions for the Japanese audience versus the international audience are a little different. I don’t have to introduce Buddhism to a Japanese audience, but in Japan I feel that people are pressured to conform to societal expectations—that women have to behave in this way, or that men doing [certain things] is not manly enough. That is something that I want to break in Japan.

[For English readers,] I really want to introduce Buddhism and how accepting it is. Many people are suffering with religious values that are limiting toward their sexual identity or sexual preferences. So, if they know more about other religions in the world, I think I can liberate them a little bit. I want to tell them that those beliefs are not the only way and there are other teachings too.

How can Buddhist teachings help someone who is struggling with their sexuality or gender identity? Actually, Buddhist teachings don’t specify LGBTQ people at all. They just say that anybody and everybody can be equally liberated. . . and not only in the LGBTQ community, but people who struggle with racial discrimination, different disabilities, or status. I don’t want to only talk about LGBTQ issues because Buddhism really is for everybody.

That being said, in 2019, the Pure Land School hosted their first LGBTQ symposium and I was a guest speaker. A master [at the training temple], Kojun Hayashida, was invited to speak. He talked about the story from one of the main sutras we read, called Amida Sutra. There is a pond of lotus flowers in the pristine Pure Land pond. . . and there are many colorful lotus flowers and these flowers shine in their own colors of blue, yellow, red, and white. He said that diversity is to be celebrated and that we should be shining in our own color.

In order to spread the Buddhist message of equality, I designed a rainbow sticker with praying hands in the middle. The Japan Buddhist Federation of 23 Japanese Buddhist schools agreed to issue this rainbow sticker that I designed. These are for anyone who wants to display them, at temple gates, bulletin boards or by anybody, even if they don’t belong to any Buddhist group.

Is the idea that people might see them and enter the temple for advice and support? Yes. [For example,] when Japanese people die, monks give the spirit a different name. But these names are gendered. . . different names for men and women. When people identify with a different gender to their sex assigned at birth it’s unpleasant because [the posthumous name] is not actually how they want to be named. We should create an area where people can open up and talk about how they want to be named once they pass away. That kind of communication is something that I want to encourage.

In your memoir’s title, you say “Be Who You Are.” What does that mean to you personally? It’s hard to be who I am. I am a Buddhist monk and there is a certain expectation and image tied with being a monk. [It means] to be free of desire, quiet, wise, humble, minimalist. . . those kinds of images. I felt that people started viewing me as this serene, pristine, perfect being, and that is not who I am. I tried to kind of perform, to look like a Buddhist monk and uphold that image for them, but that wasn’t making me happy.

I didn’t want to talk about my sexual desire. I didn’t want to be honest and complain. I didn’t want to be funny. And because I was not really myself, I wasn’t connecting with people. I couldn’t empathize with or help people in the best way possible.

That was not a sustainable way for me to continue helping people, even if I wanted to. The answer was not to try harder but to have the courage to reveal my true self. That way I could truly be friends with people. Unless people felt they could safely open up to me, I couldn’t help them. I feel that people are too ashamed to talk about their vulnerabilities to monks because they think that monks are these perfect people who must be respected, so they don’t really get to the point of what needs to be discussed.

Your book includes a moving account of how, while training as a monk, you approached a senior teacher with questions about what you could wear. Can you tell me more about how that conversation went? Since I was young, I’ve been a person who likes to dance and sing and put on something sparkly. I like to wear skirts and pink clothes. But I started hiding myself because people were humiliating me. In the US, I met many people who are very expressive and wear colorful clothing, which was eye-opening to me. I didn’t know that there was an environment where it was OK for me to be myself. I didn’t want to give that up. I was always concerned, If I become a monk, would I have to give up being who I am?

Kojun Hayashida, the master monk in my training temple, was very respected, knowledgeable, and open-minded, so I asked him [about wearing beautiful things such as accessories]. He told me, “Well, in Japan, Buddhism has been evolving. . . Monks can get married now. . . Monks can have children now. Monks have multiple jobs. . . because that was necessary for Buddhism to survive in Japan. Some monks are wearing scrubs if they are also doctors. So, if you wear something shiny, so long as you are able to deliver the message of Buddhism, which is that everybody can be equally liberated, I don’t think it is a problem.”

He cleared the clouds above my head and he gave me validation to stay as who I am, and to be a proud monk.

You also write about the bodhisattva Kannon (Guanyin in Chinese). Does this deity have a special significance for you? [In Pure Land Buddhist temples] there are usually three Buddhist statues: Amida in the middle, Kannon on the left, and Seishi on the right. After my master told me that it is OK to dress in beautiful clothes, my father [who is a Buddhist priest] asked me, “Oh, do you remember Guanyin? Do you know why he is wearing dazzling accessories and embellishments?” He said that Buddhism has been evolving. In the beginning, neither humble monks nor bodhisattvas wore anything lavish because they didn’t own anything, they didn’t have money. But The Flower Garland Sutra says, “In order to inspire people, in order to gain respect from people, you have to look beautiful, because sublime virtue requires sublime appearance. Also, you have to be excellent in knowledge, and surround yourself with majestic people. For the first time, then, you can gain respect and help people. So, if you want to be a bodhisattva like me, you should dress up and look pristine.”

After learning this, I thought, “Wow, that’s so true. We worship Kannon so why can’t I try to be like him or her?” I feel like I empathize with Kannon so much because Kannon was considered a male bodhisattva of bravery in India but was later depicted as a mother-like figure with very soft features and considered a bodhisattva of mercy. He is considered a male, but I don’t know if Kannon considers himself a man or a woman. It is the same with me. I know my body is male, but am I a man or a woman? I don’t even know myself.

Your father is also a priest. How does he view your unusual path as a Buddhist monk? My father is an emeritus professor at a Buddhist university and knows much about Buddhism. He lives in a rather conservative way and doesn’t wear anything lavish or colorful. He has always known that I was a homosexual, [but] he was very afraid that I would be targeted and humiliated within the Buddhist community when I publicly came out. But actually, there have never been negative comments from the community.

He has become comfortable with me expressing my sexuality because he has seen many people supporting me. He has received compliments from his professor and monk peers, and also letters and words of gratitude from the followers of our temple. Recently, he has given me suggestions on my fashion too, about which heels to wear!

My father is not really trying to change the overall situation. He likes to keep things in the comfortable way as they are now. However, he thinks the Japan Buddhist Federation should eliminate discriminatory lines from the sutras. For example, when women are reborn in the Pure Land, it says they will be reborn as male. Or, in a sutra from the Pure Land school nuns and novices are listed as “ignorant.” I [also] think these lines are so outdated. I get offended, so during the monk training, I would secretly skip these lines.

Do you want to say anything else? Well, a lot of people think that I am not a real monk. I know that I am not following the traditional image, but I believe that the essence of being a monk is to help people. So, I have no hesitation in tackling the problems people face today while utilizing my uniqueness.

Furthermore, I want to inspire other religious leaders of the world to re-examine their conceptions and teachings against LGBTQ people so that all of us can feel safe to be ourselves and shine in our own color. If I can contribute to that, what people think of me does not matter at all.

♦

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.