For many people, fashion means expensive clothes catering to momentary trends that are made by global conglomerates and draped over emaciated models—the epitome of the consumerist culture that many Buddhists hope to break free from. But artist and author Yumi Sakugawa wants to change our approach to fashion, which she sees as an opportunity to practice mindfulness.

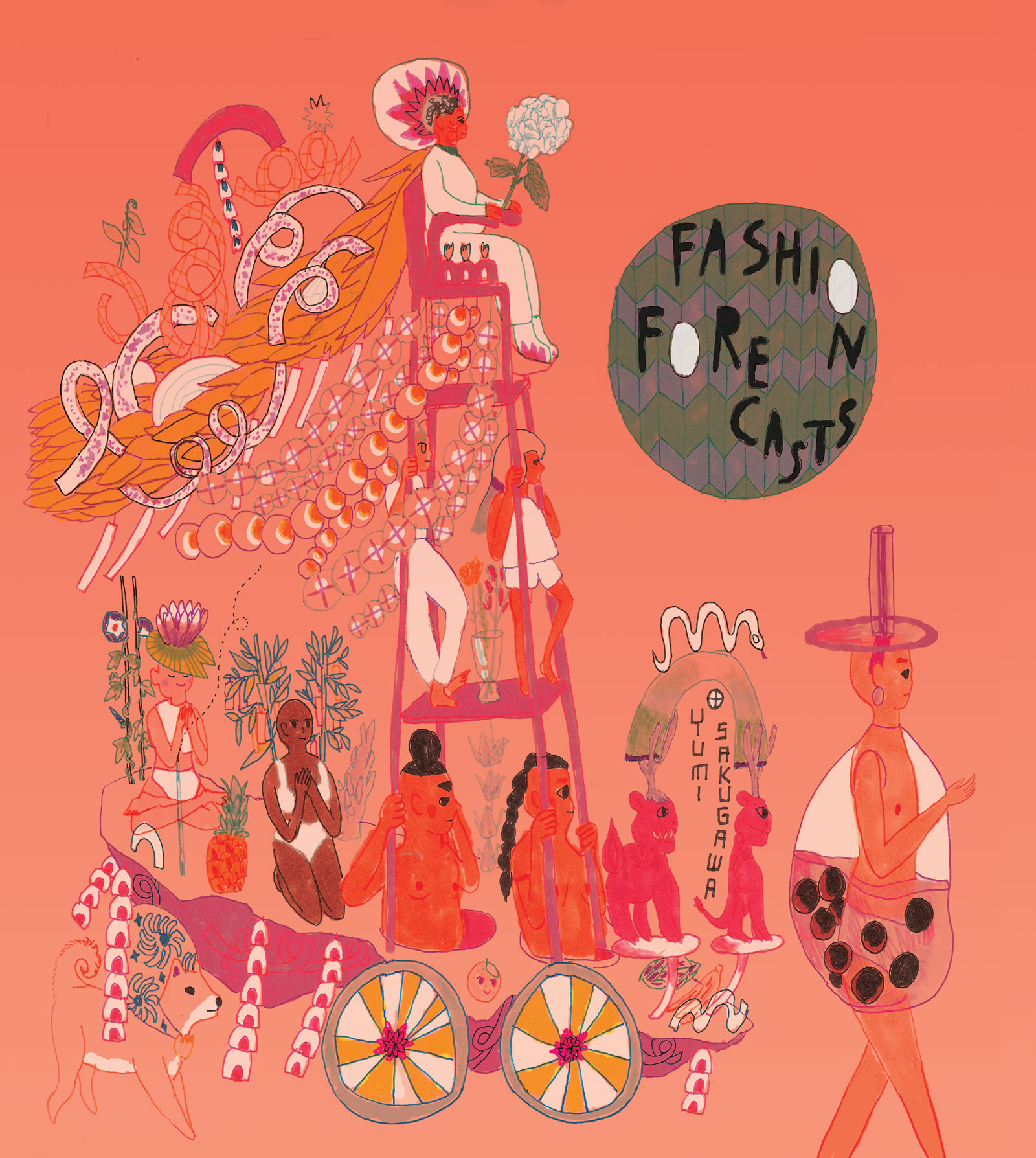

Sakugawa began to explore this new approach in 2016 with her exhibit, Fashion Forecasts, a collaboration with the Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center (APAC). That project has culminated in her latest book, Fashion Forecasts (Retrofit Comics, October 2018), which looks at the ways fashion, clothes, and beauty can be feminist, environmentally conscious, and—as the publisher’s description promises—“possibly bring you closer to enlightenment.”

The series of drawings that make up Fashion Forecasts are like thoughtful comics with captions that lead readers through Sakugawa’s various designs and the concepts they explore. Her illustrations include a mindful makeup ritual, a dress made out of the traditional Vietnamese dish pho, and a step by step guide to figuring out what outfits are right for you. As one of Sakugawa’s graphics notes, “You can always pick a new outfit.”

Sakugawa, whose other books include Your Illustrated Guide To Becoming One With The Universe and There Is No Right Way to Meditate: And Other Lessons, took some time to chat with Tricycle about Fashion Forecasts, why spirituality has always been infused with her art, and how she is learning how to pick her own outfits mindfully.

What made you begin thinking about the connections among fashion, mindfulness, and identity?

Fashion Forecasts originally started with drawings that I was doing for myself, which I would post on Instagram and Facebook. I wasn’t planning to turn it into a book or anything—it was just an informal series that I did on and off when I had nothing else to do. I didn’t think much about it, but people really seemed to respond to it.

About a year later, I got an email from the curator at the Smithsonian APAC inviting me to be part of a pop-up culture lab on intersectionality. He asked me if I had any ideas, and I said, “Well, I’ve been doing these fashion forecast drawings, which could be an interesting way to explore Asian American identity, gender, and intergenerational cooperation.”

From there, it became an installation and a zine, which later became a book.

Why were you drawn to fashion?

Over the last few years, I started to get excited about my own fashion choices. I felt that I was exercising my own agency in a very intentional way with how I presented myself to the world. It became a daily practice of honoring who I am in the moment. When we are mindful about fashion, it can help us become aware of how our seemingly small daily choices inform both who we are and who we want to become.

Walk us through that process. Let’s say you’re getting ready for your monthly Sunday book club brunch. How would you mindfully pick an outfit?

So much of it is intuitive, but the main question I ask myself is “how does this fashion choice affect the gathering?” For a brunch with friends, I don’t want to be too stiff, which could make it feel like a chore, but I still want to show that I care and value their company. Pops of color, like some bright red lipstick, and playful accessories help bring some extra fun and fit well with a daytime event. This approach lets me be artistic in my choices while heightening the experience for the whole group, even if some people might not notice or appreciate the subtle influences.

I’m always trying to vibe into the energy of the event. I often try on different options until I get a feeling in my chest that is similar to when a final puzzle piece has slid it into place, and I think, “This is it.”

Both your book and the original exhibitions place an emphasis on being more environmentally conscious. One of the hardest parts about loving fashion is knowing that it’s not great for the environment and that workers aren’t always treated well.

Absolutely. I don’t have the perfect solution, but one way of approaching the ethical question is to buy clothes that I know I am going to be wearing for a long time. That means no throwaway fast fashion [cheap clothing made to keep up with trends] that is only good for one season and will be forgotten the next.

I also love swapping clothing with friends. As a matter of fact, I am wearing a jumpsuit right now that a friend didn’t want anymore. The idea is to buy as few garments as possible and give a lot of life to the clothes I already have.

The original Fashion Forecasts installation featured a “community cape” that was designed to be worn by several people at the same time. Can you tell us about the that idea and how it brought people together?

That was probably one of my favorite drawings, and I was so glad that it was translated into a real-life prop for the exhibit by my friend Robbie Monsad, who had worked on costumes at the LA Opera House. Because fashion can be isolating, I liked the idea of an outfit that could only function when it’s being worn by multiple people. Fashion can bring people together, but often it ends up creating more distance.

There were two iterations of the community cape. One cape was for dialogue, and the other was a silence cape. A lot of interesting things can happen when strangers are talking to each other, and throughout the exhibition, there were a lot of people shuffling in and out of the cape having those connections and conversations. But sometimes people are more introverted and want to be in good company without the pressure of talking.

Another part of the installation that stood out to me was the drawing of an outfit that served as a wearable altar to one’s ancestors. The outfit is so striking because it allows visitors to give fruit and other offerings to the altar as a way of honoring their family history. How did you come up with that concept?

I started wondering how fashion can be a vehicle for exploring Asian American identity and how we think about our origins. I wanted to offer a counterbalance to the cultural appropriation that happens in fashion, where wearing chopsticks in your hair or kimonos becomes trendy. To me, the opposite of that appropriation is Asian Americans owning their own heritage and origins in a personal and sacred way.

I created the living altar because those traditions do exist in many Asian and Asian American cultures, and also because seeing family altars in my grandparents’ home is a sensory memory that feels important to me. I didn’t grow up with altars in my parents’ home, and so this installation is my attempt to capture a tangible sense of ancestral lineage and ritual that, in many ways, got disconnected when my parents immigrated to America and raised me here.

You’ve said before in interviews that everyone always asks you if you are a Buddhist because so much of your work seems to draw on Buddhist themes. What’s your relationship to Buddhism?

I am inspired by Buddhist philosophy, but I wouldn’t formally identify myself as a Buddhist. With my own spiritual identity, I prefer to keep it undefined because there is not an official organized religion that I feel the need to identify with.

Did your parents or ancestors practice Buddhism? Where does that influence come from?

My parents and ancestors are culturally Japanese Buddhist. I wouldn’t go as far to say that they are religious, but my grandparents did have family altars in their homes and both sides of my family would celebrate the annual Obon, a Japanese Buddhist custom to honor the spirits of the dead. So I grew up with those influences, which I think are more cultural than religious in the way that I experienced them.

Then from 2008 to 2012, I worked for a startup founded by Deepak Chopra’s daughter, Mallika, and I think that having immersed myself in the self help and new age world, I picked up a lot of things on meditation and mindfulness. My biggest introduction to meditation and mindfulness was through Eckhart Tolle’s A New Earth: Awakening to Your Life’s Purpose and The Power of Now. So much of what Tolle writes about feels very Buddhist in nature, but he also doesn’t explicitly identify as Buddhist.

What did you ultimately take away from working on Fashion Forecasts?

It took me a long time to allow myself to get into fashion in my own personal way. Growing up, I saw fashion as this exclusive hierarchy, and at the top of this pyramid there’s the celebrities, or the rich and powerful, who everyone else is trying to emulate.

I started drawing Fashion Forecasts to try to subvert that power structure. I wanted to see fashion as a more democratic structure, where everybody can participate regardless of age, body type, and so on. Everybody should be able to practice agency in how they present themselves to the world.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.