Anyone who has mindfully washed the dishes knows it’s not as easy as it sounds. So how about being mindful while binge-watching a true crime documentary on Netflix? That’s a challenge.

The addictive, infuriating, and wildly popular “Making a Murderer” can be seen as an eye-opening parable of how failing to be mindful can have tragic consequences in the justice system. The series, with its kaleidoscope of shifting facts and high-stakes subject matter, also presents a good opportunity for viewers themselves to transform mindless entertainment into mindful observation.

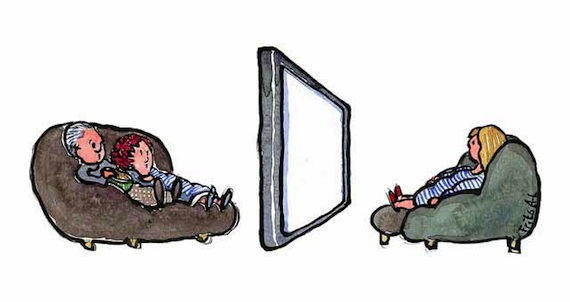

The 10-part series begins with the Mark Twain quote: “It ain’t what you don’t know that gets you into trouble. It’s what you know for sure that just ain’t so.” And throughout, I had to ask myself what I really knew for sure. The goal of watching with bare attention, without judgment, required constant effort as I rode my own little living room roller coaster of doubt, certainty, aversion, outrage, and self-righteousness.

“Making a Murderer” starts with Steven Avery being released from prison after serving 18 years on a sexual assault charge later overturned because of DNA evidence. What happens next is seemingly an open-and-shut case. Wisconsin photographer Teresa Halbach, 25, disappeared on Halloween in 2005. Her charred and fragmented bones were found days later in a burn pit at Avery’s home. Yet, if we are to believe the filmmakers’ case, it seems that law enforcement brazenly framed Avery and his nephew Brendan Dassey for the young woman’s 2005 murder.

Related: The Mindfulness Wedge

The series has inspired a petition calling for a presidential pardon, as well as a fiery debate between defense attorneys and the prosecutors, the latter who claim the filmmakers left out key pieces of damning evidence. As the case is retried in newspapers, People magazine, Reddit forums, those of us who have been swept up in the series’ exculpatory tenor may want to examine our own fast-brain thinking. While the series exposes major flaws in the case, it does not “prove” that Avery and Dassey are innocent. Even so, as viewers we are ready to impeach the prosecutors as quickly as they seemingly rushed to lock up Avery and his nephew.

Despite the Zen aphorism that “where there is great doubt, there will be great awakening,” we too are ready to snap our minds closed as thoughtlessly as we might scratch an itch. The desire for certainty is compelling.

Beyond letting us observe how we cling to our own views, the series presents countless instances of human “thinking” that is really just reaction—fear, outrage, self-interest. For example, the Wisconsin media—and presumably the jurors—seem overtaken by a visceral reaction to the gruesome story prosecutor Ken Kratz paints in a lurid pre-trial press conference. Even compassion—for the woman who was murdered, for the victim’s family—is an emotion that should be felt, observed, and then put aside when trying to weigh the facts. This is the distance that can be cultivated with mindful attention.

Related: Mindful Tech: Learn the advantages of breathing through your inbox

As defense attorney Dean Strang points out, many problems in the criminal justice system stem from “unwarranted certitude.” One egregious example: Len Kachinsky, the attorney who was appointed to defend Dassey, the cognitively challenged 16-year-old who was also charged in the murder. Before he has even talked with his client, Kachinsky presumes guilt and damns him in a press conference, saying that his client was “morally and legally responsible,” but had been influenced by Avery, whom he calls “evil incarnate.” Pretty incendiary words from a defense attorney.

Whether or not you buy the contention that Avery and Dassey are innocent, the series pries open a crevice of reasonable doubt that should have prevented the convictions, and as such it may cast light on problems in the justice system. At the very least, it gives each one of us another chance to practice what it means to pay attention, without judgment, and to imagine what a truly mindful criminal justice system might look like.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.