When Tenzin Dickie was growing up in exile in India, she didn’t have access to Tibetan stories. “We grew up in Tibetan refugee communities that were in the process of settling down, and the first order of business was to worry about survival,” she told Tricycle. “Literature and art came later, so those of us born in exile grew up orphaned from our literature.”

Now, as an editor and translator, she is working to center and elevate the hidden stories of Tibetan life in exile. In the process of tracing these histories, she has come to view Tibetan literature as written in political and territorial bardo, marked by both pain and possibility. “The bardo is a stage of roaming in between destinations,” she says. “For Tibetans right now, we’re living in political bardo. It is a place of loss, but it is also a place of possibility. It is where change can happen.”

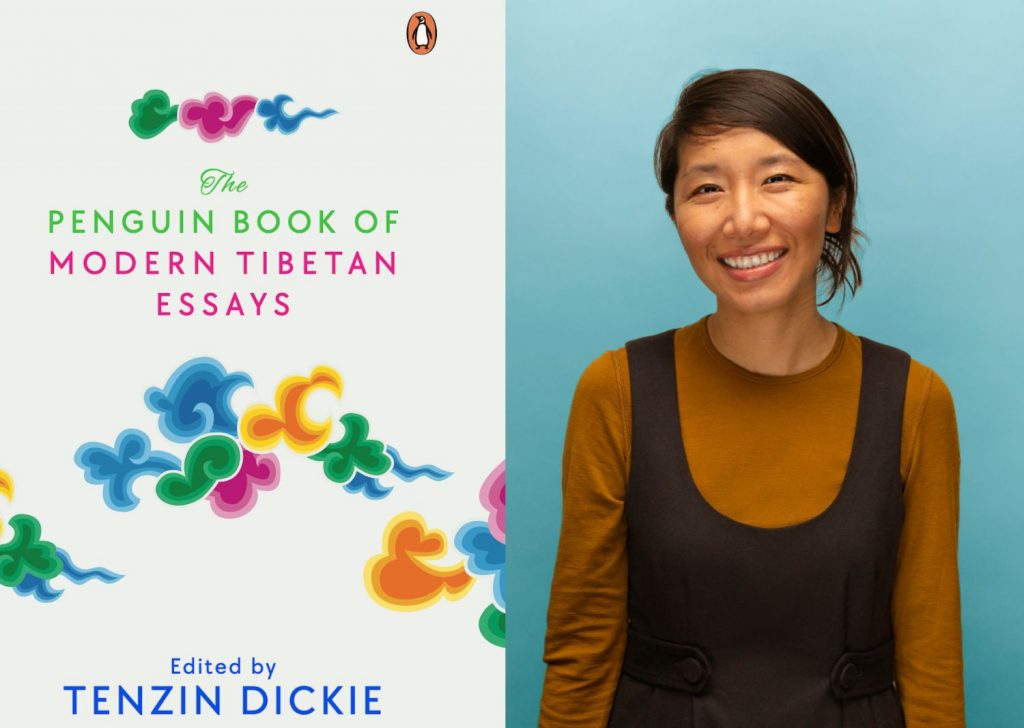

Her new book, The Penguin Book of Modern Tibetan Essays, features essays from twenty-two Tibetan authors from around the world, offering a powerful portrait of both the pain and the hope found in exile. In a recent episode of Tricycle Talks, Dickie spoke with Tricycle’s editor-in-chief, James Shaheen, about the history of the Tibetan essay, the complexity of exile, and how modern Tibetan writers are continually recreating the Tibetan nation.

In the introduction to the book, you share your first experience trying to write an essay as a middle schooler, and your brother said to you that an essay is a piece of writing that is true. How have you come to understand this statement, and, to turn your own question back on you, why does it matter if writing is true? It matters because we can tell when something is true. It speaks to us. We can feel its power, and we can feel it affect us. You know when someone is writing something that changed them—when you are reading it, it changes you too. The best thing about an essay, especially if the writer has put their whole heart and soul and artistry into it, is that it feels like a very true thing, and as you are reading, it’s a truth for both the writer and the reader.

You draw from the Buddhist notion of an act of truth, or a satyakriya. So what is an act of truth, and how does it create reality? An act of truth is basically a declaration of truth. It’s like an oath or a statement of truth that enacts itself and creates itself into being. What is being said is not just an expression—it’s also action. Perhaps the best way to talk about this is to look at how Buddhist literature talks about acts of truth.

In the Jataka tales, there is a story about a woman who goes to hear a teaching. She becomes so entranced by the teachings that she completely neglects her child sitting beside her. He goes off and is bitten by a snake, and he gets poisoned. The child is now in mortal danger. The parents are distraught, and they try to look for a way to save him. A monk tells them that the way to save this child is through acts of truth.

The parents start one by one. The father says, “By the truth that I’ve never seen a monk who was not a scoundrel, may this boy live.” The truth of his words indeed has a medicinal effect: power starts withdrawing from the boy’s body, and his legs become free of poison. Now, it’s the mother’s turn. She says, “By the truth that I have never loved my husband, may the child live.” Poison withdraws from the boy’s trunk, so now only the upper part of his body is still filled with poison. Finally, the monk says, “By the truth that I’ve never believed a word of the dharma and thought it only to be nonsense, may this boy live.” Lo and behold, the child is now completely free of poison.

Now, these are expensive truths. It costs something to express them. And the point of the act of truth is that it works. The truth has this enormous power that no one can deny. Thinking of the essay as an act of truth has so much resonance for me, especially when it’s a deeply personal essay that costs the writer something. The word has so much power.

You say that acts of truth transform both the writer and the reader. So how were you changed by writing and reading the essays in the book? When we were growing up in exile in India, if we wanted Tibetan stories, we couldn’t find them. Working on this book was a very special experience for me because it felt like I was privy to this hidden Tibetan history. There’s so much that is unsaid and hidden about the Tibetan exile experience, so much that I think we are only now beginning to excavate and appreciate. And it needs to be written now because otherwise, all of that memory will be erased. If we don’t record these stories now, they will just be lost. Reading these essays, it was incredible for me to really learn what older generations went through as the first settlers in exile. It makes me appreciate all the more their enormous achievement in creating this vibrant Tibetan exile.

If people don’t write their own stories, then we can never know this history. We can never know that experience. Especially for Tibetans, so much has been said and written about us, and very often it is not by us. The truth of Tibetan life is so important and so crucial because of where we are in our history right now. All of this makes Tibetan tellings of Tibetan stories all the more important because we have to say what happened to us. I feel like all Tibetan writing, to some extent, becomes witness statements.

You write that to write as Tibetans is to continually recreate the Tibetan nation. What does this look like? Especially for Tibetans outside, we don’t have access to Tibetan land. So what we have access to is the cultural content of our lives. For me, in this time and place, Tibetan literature serves as a placeholder for the Tibetan nation. I can’t live in Tibet, but I can live inside Tibetan literature.

You refer to Tibetan literature as written in the bardo. So what does it mean to write in the bardo? The bardo is this intermediate stage between death and your next life. It’s a stage of roaming in between destinations, of homelessness, of wandering, but also of possibility. For Tibetans, right now, we’re living in political bardo. We’re living in territorial bardo. That’s what exile is. Tibetan writing in exile—in the bardo—is at a crossroads. It is a place of loss. It is a place of pain. But it is also a place of possibility. It is where change can happen.

Many of the essays in the collection focus on the complexity of living in exile, and you explore this dynamic through the lens of what psychologists term ambiguous loss, or a loss where it is extremely difficult to find closure. So how has this loss shaped Tibetan writing, and what role does writing play in trying to create a sense of closure? You know how things that are born on the internet are called “born digital”? I feel like Tibetan writing born after 1959 is “born exile.” After 1959, Tibetan writers became bilingual simply because of their political situation. For exiled Tibetan writers, there is an enforced distance from older Tibetan literature simply because of the fact that we were born in exile. We grew up in Tibetan refugee communities that were in the process of settling down, and the first order of business was to worry about survival. Literature and art came later, so those of us born in exile grew up orphaned from our literature. Exile defines not just our lives but also our literature.

Exile permeates what we read, and it permeates what we write. There’s an essay in the book by [the Tibetan writer and activist] Woeser about the Dalai Lama‘s Gar dancer, Garpon La. He learned how to dance Gar, and then, for the next twenty years, he was in labor camps, and all the dance was beaten out of him. It was violently stripped away and destroyed, and he couldn’t even think about getting back to dancing. For him, it had been a way of life, and he couldn’t even conceive of getting back to it because of the trauma that he had suffered that was associated with it. It took coming to India, visiting the Dalai Lama, and receiving a blessing from the Dalai Lama commanding him to bring back Gar dance that Garpon La was able to remember how to dance. Not only did he dance it himself, but he also taught it and revived the tradition of Gar dance.

This goes to show that there are many different forms of exile that Tibetans suffer from. I think we’re all trying to find some way to live in samsara in exile and make art at the same time. That’s our act of truth.

That’s a remarkable story, and I wonder if the writing in this book is a similar effort to connect again and to establish the reality of Tibet again. I would say yes. Part of the reason for this book is as simple as saying we’re here. We’re still here, and we will continue to be here. I hope that when people read the book, they understand what Tibetans go through as they live their life with exile as their daily habitat. The book is an assertion of our identity, an assertion of our existence, and an assertion that we will continue.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.