For meditator and dharma teacher Jo-ann Rosen, Buddhism has been a vital lifeline in helping her transcend the wounds of the past. A thirty-year practitioner in the Plum Village lineage established by the late Zen master Thich Nhat Hanh, Rosen says the tradition’s teachings and rituals have supported her in understanding and having compassion for her own suffering, including intergenerational trauma and parental neglect.

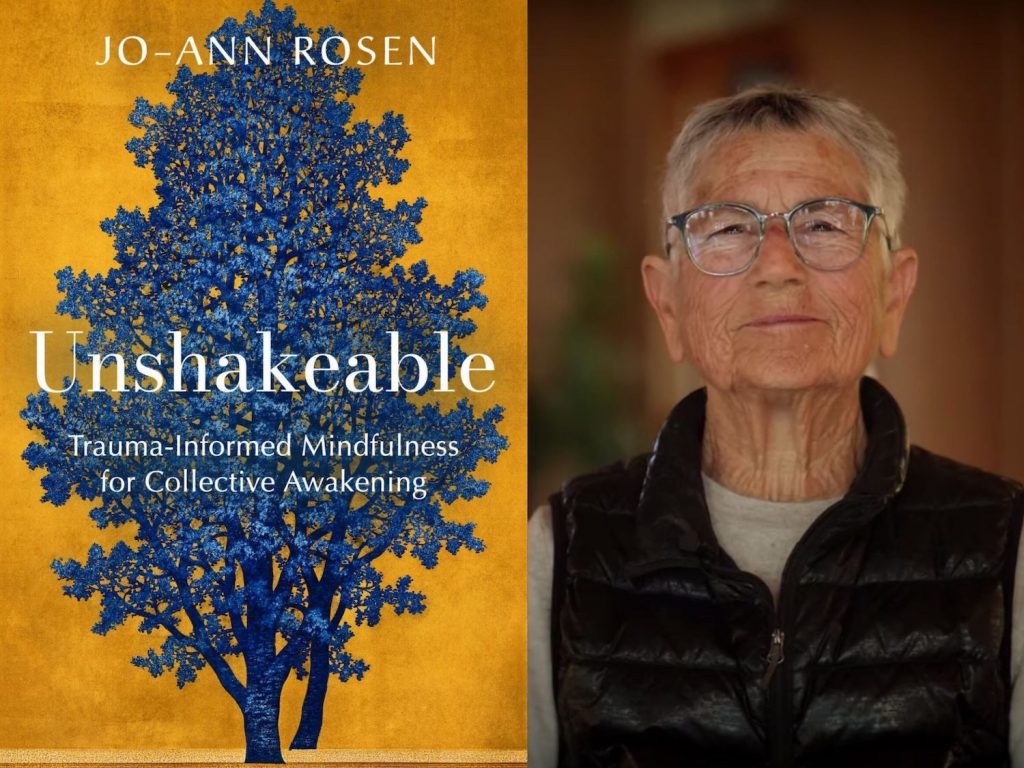

Rosen is also a psychotherapist who has been intensively curious about neuroscience as it relates to the importance of a well-regulated nervous system in transforming difficult emotions. Her latest book, Unshakeable: Trauma-Informed Mindfulness for Collective Awakening (Parallax Press, 2023), takes a neurologically informed approach to Buddhist practice as critical in helping to heal trauma and restore connection. Rosen sees the book as a guide to a spiritual journey that can alleviate suffering and build resiliency at both the individual and collective levels of society.

Rosen recently spoke with Tricycle about meditation sickness, somatic psychology, and the liberating potentials hiding in the “window of mindful opportunity.”

How did the idea for Unshakeable take shape? Trauma played a significant role in Thich Nhat Hanh’s development of this tradition, because he created it partly in response to the unbelievable suffering [he saw] happening right outside his door [during] the Vietnam War. [Through his teachings] I saw that many of the insights and practices of the tradition already help us to regulate our nervous system.

Then a few years ago, I read Trauma-Sensitive Mindfulness by David Treleaven, which looks at the need to meditate with an awareness of trauma in order not to aggravate traumatic stress symptoms. I saw a value in adding this perspective to the Plum Village lineage.

At the same time, as a therapist, I know that therapy has lots to offer individuals—but only to those who can access it or afford it. Therapy is kind of an elitist opportunity. The masses of people in these times who are suffering need support that is more accessible. When I learned about the healing value of somatic psychology—exercises that can help release painful emotions from the body—that got me curious about the body’s role in suffering, and about the impacts of a dysregulated nervous system.

With Unshakeable, I am bringing meditation and psychotherapy together in a way that makes it easier for lay practitioners to access Buddhist insights, metabolize trauma, and cultivate resilience.

Why is a better understanding of the nervous system important for processing suffering? We humans are way more rudimentary than we think we are. We are reactive, and while that reactivity previously served us well as hunter-gatherers, it mostly doesn’t serve us anymore. Fortunately, we have the potential built into us to grow out of that, and if we can realize this, we can give ourselves more space to be compassionate about the mistakes we make, because we’re programmed that way. And if I can see that in myself and I can see it in you, then there’s a lot more space and less reactivity to want to fight with you when you disagree with me.

What are some ways that neuroscience dovetails with Buddhist practice? When we are practicing mindfulness meditation, where we are calming the mind and looking deeply at the nature of all phenomena, we are engaging and strengthening various parts of our brain, including our limbic system, vagus nerve, and prefrontal cortex. What we gain by fine-tuning these neural networks is a greater ability to self-regulate our nervous system, and a greater capacity to see and understand things more clearly and accurately.

A key aspect of the Plum Village tradition is the Five Mindfulness Trainings, which are a code of ethics that help us develop actions of body, speech, and mind that enable us to live an ethical, compassionate life. Applying a neuroscience lens, we can view them as contemplations to help us find an optimal balance between safety and a deeper understanding and healing. They help us to recognize and resist our nervous system’s overfocus on threat, and to cultivate reverence for life, generosity, love, and healthful choices.

Thich Nhat Hanh taught about the various mental formations that exist in what he called our “store consciousness,” and using the analogy of a garden, said we should take care to water our wholesome seeds, such as compassion, joy, and generosity, that contribute to our well-being, and not to nurture our unwholesome ones, which include anger, greed, or fear, which cause us ill-being. From a neuro-based perspective, we can view these seeds as our neural pathways, which produce the full range of human emotions. When we nourish a particular pathway, the corresponding emotions will bloom.

In your book, you refer to a state of the nervous system where it feels safe to process intense emotions called the “window of mindful opportunity”—a term similar to the “window of tolerance,” coined by clinical psychiatry professor Dan Siegel. Could you explain the difference between the two terms? The window of tolerance is about how much activation your nervous system can handle. When we feel threatened, our nervous system gets overactivated and we go into an automatic defense mode. I call this state of hyperarousal the red zone. On the opposite end is the green zone, a place of rest and recuperation, where you can restore your depleted nervous system. In the middle is the area of mindfulness, where we feel balanced enough to explore difficult aspects of our inner lives. It’s that curiosity that compelled me to reframe the term, as the word “tolerance” for me is tension-producing. “Opportunity” seems more appropriate, because when we feel at ease and comfortable enough to be mindful of our difficult emotions, it can be liberating, exciting, and positive.

“If people are able to heal more, they are better able to tap into how they can be of benefit to others.”

You write in your book about “meditation sickness,” where some practitioners can experience adverse effects from meditation. What should we know about this phenomenon? If meditation is sustained focus in a relaxed, alert way, that’s a skill that everyone needs to develop. But meditation is a practice that has been proven to change the brain, and so it isn’t something to be taken lightly; some people can get into hot water. One pitfall that can arise is that people’s automatic traumatic responses can become reactivated. Memories of their traumas may resurface, and that can be painful, and they may not know how to deal with them. Another hazard that can arise is spiritual bypassing, where people perceive that nothing bothers them or that they are above their traumas, when in fact, they are sidestepping their unresolved emotional issues or avoiding healthy developmental skill building. People need to know that these risks exist. They need to be in touch with their body and mind enough to know what’s going on, and that they may need some accompaniment and guidance to practice safely.

Your book also discusses the neurological benefits of being part of a strong and self-aware community. Thich Nhat Hanh taught about the insight of interbeing—that all of life is interconnected with each other, there is no separate self. In the Plum Village tradition, individual and collective awakening are inextricably connected, and the sangha can provide support for our spiritual journey. From a neuroscience perspective, when we can see ourselves as one cell in the sangha body, we can work together to transform the traumas in our personal lives and our human societies.

If there is a core of people who can hold the energy of compassion, of curiosity, of hurt without becoming dysregulated, that can help others to calm down enough to get a wider view of what’s happening in their lives. That is the power of emotional coregulation—we can help each other to stay centered and stable. Facing suffering together can be much more powerful than facing it alone—that is, when the collective is well-functioning.

Within our sanghas, we want to look at the ways that inequities play out among different peoples. We have created a human culture that is not healthy—no matter where you go in the world, there are inequities, whether connected to race, religion, gender, sexual orientation, age, or other categories. Acknowledging these aspects of people’s lived experiences, and the power differences and biases that may be at play in our sanghas, helps us to engage with each other with more understanding and compassion, and foster sanghas that offer a true sense of belonging and acceptance.

At a time when we face crises such as climate change, war, and food insecurity, how optimistic are you that humans can apply the insights of neuro-informed Buddhist practice to get our personal and collective houses in order? I’m actually not optimistic, but that’s kind of irrelevant in a way. I have faith in two things. One is that looking deeper has made a difference in how I act. So I have faith in my own journey, from what I’ve experienced on the path of mindfulness. I’m much less reactive, although by far not unreactive. I’m much more understanding and give people more slack.

I also feel that if people are able to heal more, they are better able to tap into how they can be of benefit to others. People who are hurting are engulfed with their hurt. But if they can become more resilient, they are better positioned to have a social purpose—and the act of engaging in altruistic behavior is itself a healing path.

So it doesn’t really matter in some ways whether the world is going to survive or not. If we can react to the world—not from a place of trauma but from a place of clarity—and be part of a group with others who also have that sense of clarity and an ability to self-regulate, maybe that will be a beneficial contribution regardless of outcome.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.