Werner Vogd is a German sociologist and anthropologist who chairs the department of sociology at the University of Witten/Herdecke. Vogd is a practicing Buddhist and wrote his dissertation on the epistemology of Theravada Buddhism, but his research interests range widely—from social dynamics in hospital management to forensic psychiatry to end-of-life care.

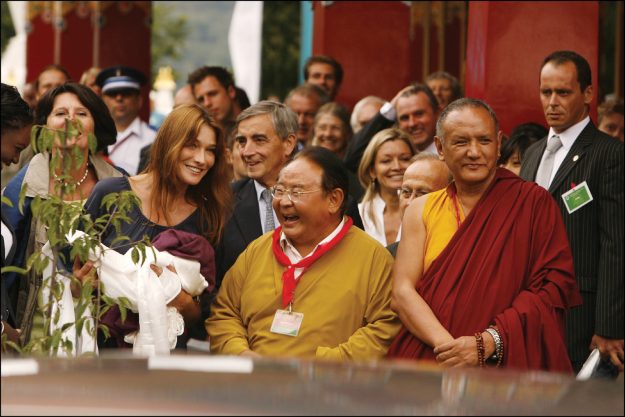

In recent years, Vogd has conducted hundreds of interviews with students of Buddhism in Germany as part of an expansive investigation into the relationship between practice and self-reported happiness and well-being. Part of that research has focused on the experiences of members of the Tibetan Buddhist organization Rigpa, founded by Sogyal Rinpoche, the popular teacher and best-selling author who abruptly retired in 2017 after students accused him of ongoing sexual, physical, and emotional abuse. In fact, reports of abuse had dogged Sogyal for decades. He died in August 2019.

Der ermächtigte Meister (“The Empowered Master”), a book based on Vogd’s interviews with Sogyal’s students, explores the tensions and contradictions experienced by practitioners when they are led by a teacher who they believe possesses great wisdom, but whose actions are unquestionably abusive. This problem, Vogd argues, is rooted in the tendency of Western students to deify their Buddhist teachers, as well as in a general lack of checks and balances on teachers’ behavior—and egos. “One of the most important insights of our study,” says Vogd, “was the realization that teachers must not be left in a vacuum; for their own protection they need community members who are strong enough to keep them mindful of their role as spiritual leaders.”

In the following interview, adapted from the German quarterly Buddhismus aktuell (“Buddhism Today”), Vogd explains his findings and delves into the psychological and spiritual work—namely the cultivation of compassion—that can help practitioners navigate the student-teacher dynamic and reap its intended benefits.

Susanne Billig [editor-in-chief of Buddhismus aktuell]: Dr. Vogd, you have been researching spiritual development in Western Buddhist communities since 2013. How did the topic of abuse in those communities become part of your research? Werner Vogd: The subject of spiritual development has interested me for a long time, not least for personal reasons. We conducted many interviews with novices, advanced practitioners, and teachers from Vipassana and Zen communities, as well as from Rigpa, one of the most popular Tibetan Buddhist organizations. The topic of abuse was not actually planned as a focus of the research, but after we discovered that some interviewees from Rigpa were still traumatized by their experiences in the community, we felt we had a responsibility to look more closely at the issue.

Large communities are highly complex. You’ve conducted a great many interviews, but how can you be certain they have provided enough insight to draw valid scientific conclusions? To answer that question, I need to go into a bit more detail. The study of Rigpa was only part of a larger study that we carried out in order to show how people manage to find happiness, freedom from suffering, and well-being on the Buddhist path of liberation, and what kinds of obstacles and problems they encounter.

What does it mean to find happiness and well-being? To have well-being means to be whole—not split. It means being able to accept one’s own life—including one’s past— without striving for something else or wanting to be somebody else. This is very, very difficult, because we are the result of numerous relationships, many of which are full of conflict. We have also all gone through unpleasant things or trauma, and rather than be the person we have become, we often retreat into our fantasies.

As a result, students may misconstrue the spiritual path and misuse it to escape their personal realities. Either they believe that liberation consists of the kind of blissful state one may occasionally experience during meditation or while receiving a teaching, or they confine themselves to an abstract and symbolic interpretation of the Buddha’s teachings. For instance, after reciting a few vows they think they are bodhisattvas and munificently set out to help all sentient beings, while below the surface they are seething with anger. In other words, they are not really able to observe and accept their own emotional turmoil.

Can you describe in a little more detail how this works psychologically? Here’s an example: Someone has been badly treated by another person with whom they had a trusting and loving relationship, and now they are disappointed. Such experiences inevitably become part of us. We become mistrustful and start to treat other people badly because we ourselves are no longer able to trust. However, healing is possible only if we allow ourselves to feel and intimately know our own fears, anger, despair, disappointment, or depression at the deepest level. If this step is possible, something wonderful can happen. Our suffering begins to change into compassion and deep understanding. And then suffering disappears. The old response patterns dissolve.

Our study has shown us that people are capable of such a transformation, but it can often take ten or twenty years or even longer to develop this depth of compassion for ourselves.

Your new book is about the Rigpa community. In it you describe the many levels on which a teacher-student relationship can operate, and the ambivalent feelings that can arise in reaction to the master or the community. Can you give some examples of that? One of the community leaders we interviewed who had been part of Rigpa for more than ten years was struggling with doubt. Basically he told us this: “I know that things actually happened involving Sogyal Rinpoche, but I don’t want to have doubt, so I push it away. I want to be able to go on loving Sogyal—he’s my master, after all.” Since this senior student had split off his doubts and pushed away his own observations, it was not possible for him to develop compassion for his own ambivalent state. He was also unable to have compassion for other students who had doubts about Sogyal, as became quite clear in the interview. He was compelled to oppose them.

At the same time, he was encouraged to ignore Sogyal’s behavior by other members of the Rigpa community who were important to him, so that a network grew for the collective cultivation of oblivion. Moreover, his “love of the teacher” turned out to be merely superficial. Sogyal was loved only in his role as a master, not as a whole person who was fallible like anyone else.

We talked to another deeply committed student who turned away from Sogyal when he discovered the extent of the teacher’s misconduct, and he finally abandoned his spiritual practice because he could not bear the pain of the betrayal he had experienced. After three years, we spoke to him again, and he told us that he would be willing to forgive Sogyal for his sexual and other escapades if he would admit to them openly. This point is important, since it tells us whether the disappointment can be healed or whether the spiritual trauma will deepen. The taboo against speaking openly about the incidents (which was maintained by Sogyal Rinpoche himself and is still maintained by other prominent lamas) shielded the Rigpa students from a fundamental requirement of all serious spiritual paths: a willingness to see things as they really are. This is disastrous precisely because it prevents practitioners from developing compassion for themselves and others.

When credible accusations are made against a dharma teacher, there are always students who refuse to accept them. Either they deny the existence of the behavior entirely, or they confirm the facts but refuse to assess them critically. What do you think is happening psychologically in such cases? It’s understandable to want nothing to do with something that is unpleasant or traumatic. When nearly everyone feels that way, a systemic dynamic develops whereby the behavior of those who look away or who put on a show of confidence will be validated by the others.

Those who allow the situation to really affect them will be shaken to the core. They may cry for days over what has happened and oscillate between anger and despair for a long time before they are able to feel compassion for themselves and others again.

It is hardly surprising, then, that many students do not want to acknowledge this intense pain and instead take refuge in rationalizations and pseudo-explanations. Added to this is the fear of recognizing that they may have contributed to their own suffering by upholding the system of taboos and deceptions.

What do you mean when you describe this as systemic, and why is that important? Systemic means we are looking at relationships that may then crystallize into rigid structures. It means that we don’t put the blame on a single individual or look only there for the origin of the situation. This view dovetails with the Buddhist perspective: According to the law of dependent co-arising (paticca-samuppada), there is no fixed core of personality but rather a complex network of cause and effect from which all our entanglements and suffering arise.

The systemic perspective makes it clear that the teacher is also a product of circumstances. Students revere him. They believe he possesses supernatural abilities and shower him with love. That would go to anyone’s head. In fact, there is a clear reference in the Buddhist scriptures about the fact that vanity and arrogance are the most difficult fetters to overcome. Someone who is also psychologically vulnerable and does not have good friends to provide a check will inevitably begin to fall prey to narcissism, to believe that they are omnipotent.

The more powerful a spiritual master becomes, the more he needs somebody to make him understand that the superior position of the teacher is not his personally, but is part of a network of roles, none of which belongs to him. I believe one of the most important insights of our study was the understanding that teachers must not be left in a vacuum; for their own protection they need community members who are strong enough to keep them mindful of their role as spiritual leaders.

What is the difference between this systemic perspective and the kind of moral perspective through which one either condemns what happened between Sogyal Rinpoche and his students or attempts to legitimize it? This brings us to the crux of the problem. Some of the people we’ve encountered—students or longstanding companions or other lamas—have either declared Sogyal to be a monster or see him as superhuman.

When students see their teacher as superhuman, they believe he has magical powers and that everything he does is sacred, a blessing. A lama from the Gelug school told me that in the 1970s he had arranged to have an eminent Tibetan Buddhist visit a German community. After a few days he learned that no meals had been offered to the guest. When asked about this, the hosts replied they had assumed their visitor was so enlightened that he did not need to eat or drink.

Related: How Can We See Our Teachers as People?

Another example is that of Ösel Tenzin, who succeeded Chögyam Trungpa as director of the Vajradhatu Buddhist community in Boulder, Colorado, and who had AIDS. Unfortunately, he was firmly convinced that he would not infect anyone by having sex with them because he was protected from worldly evils by mantras and protective Tibetan spirits.

We Western students tend to elevate our dharma teachers to the status of superhuman beings. But if we are then disappointed—because even a highly skilled spiritual teacher can be stricken by dementia or fall prey to alcohol or sex addiction—we go to the other extreme and declare that the person we have just worshipped is actually a monster. Both extremes prevent us from seeing things as they really are.

This sounds a lot like the narrative in many romantic love stories. In fact, you write in your book that to commit oneself to following a spiritual path is in many ways similar to committing to a love relationship. To love another person means to accept them completely as they are, to share their woes and joys from moment to moment. That is a wonderful thing. But as soon as we begin to think that the fantasies and sensations that we had in the initial phase of bliss are eternal, true, and enduring, we are doomed to forfeit our love and be left with nothing but concepts and stereotypes.

By contrast, genuine love is associated with the ability to accept—at a deep, feeling level—the fact that all things pass. I may have a partner I love and with whom I have spent some wonderful times. And then suddenly things change. It turns out my partner is sick. Perhaps it’s a brain tumor, or an addiction that is out of control.

One part of me sees reality, but another part immediately represses what I have seen. I begin to confuse love with self-deception and withdraw into my own fantasies and projections. At this point true compassion is no longer possible, because that would mean seeing the other person complete with their tragic human flaws and their failure to meet the demands of everyday life.

In Tibetan tantric Buddhism, the master takes on a special role. In “guru devotion” students visualize the teacher as an ideal being with whom they identify and thus experience their own buddhanature. Your book describes people who feel deeply touched and transformed by this practice. Is it no more than imagination and self-deception? Tantric Buddhism offers a path that can be very effective. Unfortunately, it is often misunderstood. Take one of the most important tantric vows, the commitment “never to lose one’s love for sentient beings” and to practice this “on the person of the lama.” Anyone who actually does this can learn that the teacher is no different from him- or herself and can develop deep compassion for our transitory existence and our typical human failings.

But it is hard to grasp that the essence of all spiritual paths lies in recognizing ourselves as suffering beings who are dependent on others. We would prefer to believe that an all-powerful master can catapult us into Buddha heaven by some clever maneuver.

Legitimate teachers will try to dismantle this expectation as soon as their students have gained trust in them. In our study we found that Zen and Vipassana teachers are often quite successful in debunking such illusions. Students come to them with their fantasies of illumination and liberation, but their teachers disappoint them and thereby bring them back to real life in a positive sense.

In the case of Sogyal Rinpoche, his reliance on “crazy wisdom”— a strand of tantra whereby the teacher breaks with conventional mores and expectations in dealing with students—didn’t seem to work well. When Sogyal overturned tables or subjected his students to sexual humiliation, they did not as a rule gain the salutary insight that there was nothing transcendent behind these actions—that an overturned table is simply an overturned table, or that rough sex is rough sex and nothing more. Instead—as our interviews indicated—such scenes heightened the illusion that the students were witnessing a master who had special magical skills. Instead of waking them up, his behavior reinforced their self-deception and the risk of the kind of devastating disappointment that is associated with doubt, depression, and self-hate—anything but enlightenment.

Some people also feel traumatized when their teachers are publicly criticized for serious transgressions. The very foundation of their lives seems to crumble beneath their feet. Are there ways to cope with this other than either carrying on without criticizing at all or angrily withdrawing? Is it possible to be open to the fact that one’s teacher has behaved or is behaving in a problematic way—and still maintain the relationship? Yes; as I mentioned earlier, we have to be prepared to see the teacher as a human being who can be sick, addicted, mentally disturbed, deluded, or flawed in some other way—like anyone else. But in order to be able to do that, we must first have compassion for ourselves. I must admit to myself that I was deluded, that I allowed myself to be deceived—perhaps for twenty or thirty years. I must be able to forgive myself for having dragged other people into the illusion and for having held others back from shining light on what was blatantly manifest. Admitting this and forgiving oneself is no easy feat.

But this also has a positive side to it: To act with compassion implies that I must assume responsibility. And when I assume responsibility, I am fully aware that it will be painful, and I accept this. Of course it doesn’t feel good to criticize one’s teacher, to remove him from office or contribute to the possibility of his being sent to prison. But I can deal with my ambivalent feelings if I keep in mind that the teacher is a human being just like I am and so deserves my love and compassion, regardless of what he has done.

In Buddhism we always talk about immersion, silence, and a fundamental don’t-know mind. If I’ve been practicing that, how can I manage at the same time to remain critical—perhaps even toward an idealized teacher? I think it may be easier for a sociologist to grasp the Buddhist teaching of not-self. From a sociological perspective, people in and of themselves are not good, bad, gracious, holy, or deluded. What we think of as their innermost qualities are dependent on others.

This is why people searching for liberation take the threefold refuge: with the Buddha, who showed the way; with the dharma, the teaching of dependent co-origination—and the insight that we do not have ourselves to thank for our sense of self or ego; and the sangha, the community of practitioners. We should not underestimate the importance of the sangha: this is where people demonstrate to each other what is right and where the path leads. A teacher can only be as good as the community that nourishes her or him. The longstanding members of Rigpa now face a major responsibility. Are they prepared to confront the “monster or superhuman” dilemma in the most radical way—that is, to acknowledge that they have deceived themselves and others? Are they willing to make some hard and painful decisions in order to stand up for a new beginning—including the dismissal of certain favorite leaders who contributed substantially to the cultivation of deception?

Ultimately, the only way to avoid despair over the “monster or superhuman” dilemma and to transcend the attendant problems is to develop compassion for oneself and others.

♦

First published in Buddhismus aktuell no. 3, 2019.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.