Suppose Alice had been reading a book on American Buddhism before drifting off to sleep on that fateful afternoon. Her exchange with the Cheshire Cat might have gone something like this:

ALICE CAME TO A FORK in the forest path and was standing for a moment, puzzled as to which way to go, when she spied the Cheshire Cat sitting in full lotus position on a bough of a tree a few yards off, meditating. It looked so peaceful that she dared not disturb it, but at the same time it had such a compassionate air that she felt it might help solve her dilemma. So when it opened its eyes, she cleared her voice and said in her sweetest tone, “If you please, Cheshire-Puss, could you tell me the way to the Queen’s croquet game?”

For a moment the Cat only grinned at her, with its eyes bulging out quite alarmingly, but then it simply said, “Which would you rather do? Go to the Queen’s croquet game, or get enlightened?”

Alice did want very much to go to the croquet game, but this was a grown-up sounding question, so she felt it required a grown-up sounding answer. “Oh. To get enlightened, of course,” she said with a knowing air.

The Cat’s eyes bulged out for a moment again, and then it said, “Well, in that case, you won’t get enlightened.”

This surprised Alice, who responded, “You mean if I want to get enlightened , that will keep me from getting enlightened?”

“Precisely,” said the Cat. “The desire to get enlightened is the one thing that will keep you from being enlightened.”

“Well, then, in that case,” said Alice, ”I’d rather go to the Queen’s croquet game.”

“No, no,” said the Cat, “that won’t do either. If you want to play croquet so that you can get enlightened, that will keep you from getting enlightened, too.”

“But whatever on earth should I do, then?” said Alice, beginning to feel a little giddy from all the strange ideas she had heard since this morning.

“There’s nothing to do at all,” replied the Cat. “Enlightenment isn’t something you do, it’s something you simply are. All you need to do is remind yourself that you’re enlightened and then act naturally in an enlightened way.”

“But how can I know what’s an enlightened way when I’m not yet enlightened?”

The Cat rolled its eyes and replied, “Mercy, how can you be so ignorant, child? You’re already enlightened. You’re enlightened, I’m enlightened, the Mad Hatter, the March Hare: we’re all enlightened.”

“But if I’m already enlightened, why don’t I know? Doesn’t being enlightened mean that you know you’re enlightened?” she asked, honestly perplexed.

“Well, of course you know. I just told you so,” replied the Cat, its grin growing steadily broader.

“But if I’m enlightened, what am I doing here? And why am I lost?”

“You forgot,” said the Cat, taking a sip out of what looked like a small glass of water.

“But if I forgot once, what’s to keep me from forgetting it again? And what good is enlightenment if you can forget it?” asked Alice, who was beginning to feel quite exasperated at the Cat’s nonsense. “Now I do wish that you would tell me the way to the Queen’s croquet game. “

“Very well, then. The path in that direction,” said the Cat, waving its right paw round, “goes to the Queen’s croquet game. While that path in that direction,” it said, pointing its tail the other way, “is the goal.”

“You mean it goes to the goal,” said Alice, correcting him, but before she could ask which goal, the Cat replied, “I meant what I said. The path is the goal.”

“But how can a path be a goal?” she asked him.

“Oh, very simply,” said the Cat. “You just walk along it without thinking of going anyplace, and so wherever you go, there you are.”

“That doesn’t sound like much of a goal to me,” said Alice. “In fact, it sounds rather pointless. I want to get out of this horrid place.”

“Whatever for?” asked the Cat.

“It’s so unsettling, all these sudden changes. First I was so small that I almost drowned in my own tears, then so tall that I couldn’t get out the door. And it all happened so incredibly fast that now I don’t rightly even know who I am….”

“Well, then there must be something wrong with you,” replied the Cat. “Everyone else here likes the sudden changes. They’re quite amusing.” And with that he suddenly vanished.

Alice was not much surprised at this, as she was getting accustomed to queer things happening, but while she was still looking at the place where the Cat had been, it suddenly appeared again.

“There. Wasn’t that amusing?” it asked.

“I suppose so,” said Alice. “But I must confess that I’m getting quite tired.”

“Then how about this?” asked the Cat. Alice waited expectantly to see what the

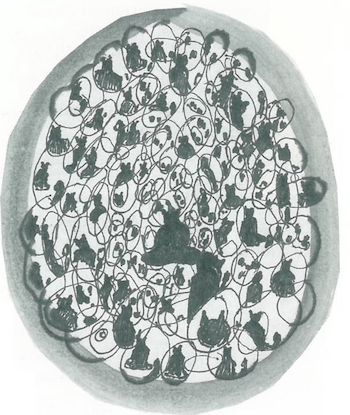

Cat would do next, but it simply sat there, grinning as before. Then gradually she became aware of a whole swarm of faint after-images of herself and the Cat whizzing past her at a dizzying speed from all sides. She looked around and noticed that a circle of mirrors hanging in the air had formed around her and the Cat. She stepped over to one of the mirrors and realized that it contained reflections not only of herself and the Cat but also of all the other mirrors, which were reflecting all the other mirrors, and so on to infinity, repeating more images of the Cat and herself than she could possibly count. “See how everything interpenetrates everything else?” asked the Cat. “I find that very amusing. I interpenetrate you, and you interpenetrate me, and—”

Alice did not at all like the sound of this last remark. “No!” she called out and turned to flee, but no matter what direction she fled, she ran into a mirror filled with the Cat’s grinning reflections. Realizing that she was trapped, she fell to her knees and started to cry. Each tear, as it rolled ever so slowly off her cheek, picked up the Cat’s reflections, which were then picked up by the next rear and then the next—until the first tear splattered on the ground and broke the spell. The Cat and the mirrors disappeared in a flash.

“Thank goodness,” said Alice. ‘Tm free.” She sped off on a path to the Queen’s croquet game. “At least with croquet you know where you are,” she thought, “with rules you can understand, and a decent beginning and end.” With this thought barely out of her head, she looked up—and there was the Cat again sitting on the branch of a tree.

“Did you say that you wanted to get out of this place?” it asked.

“Yes,” replied Alice. “Very much.”

“I must say, that’s very selfish of you,” replied the Cat. “You should make a vow that you won’t leave here until you’ve gotten all the rest of us out of here first.”

“Well, l feel that’s very selfish of you, Mr. Smarty-Puss,” retorted Alice, who was now so beside herself that she had quire forgotten her manners. “If you and all your enlightened friends want to stay here amusing yourselves, that’s your business. I’m leaving'”

To that the Cat had no answer. It simply sat there grinning, and its eyes began to bulge again. This was rather more than Alice could take.

“And I do wish that you would wipe that silly grin off your face,” she said sharply, turning to leave.

“That, I’m afraid, I can’t do,” the Cat called after her, “but I can wipe this silly face off my grin.” As Alice stopped and turned to watch, it began to vanish gradually, beginning with its tail and ending with its toothy grin, which hung gleaming in the air for a few moments. Then it too was gone.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.