This revelatory exhibition of Buddhist art from Gandhara—an ancient kingdom whose center was the present-day Peshawar valley in northwest Pakistan—nearly didn’t happen. Slated to open at New York’s Asia Society last spring, the show was delayed for six months when loans from museums in Karachi and Lahore were jeopardized by (among other things) a flood, the dissolution of the Pakistani Ministry of Culture by constitutional amendment, and deteriorating diplomatic relations between the U.S. and Pakistan. That it opened at all was a testament to the persistence and vision of Asia Society’s director, Melissa Chiu, and her counterparts and associates in Pakistan.

Gandhara, which is was first mentioned as a geographic region in the Rig Veda, around the ninth century B.C.E. was of considerable strategic and commercial importance in the ancient world. Its fertile valleys, warm climate, and above all, its central position on the busy trade routes between Asia and the Mediterranean made it valuable property. As a consequence, it suffered numerous conquests, coming under the rule of the Persians with the reign of Darius I in the sixth century B.C.E., the Greeks under Alexander the Great, and the Indian Mauryans, who introduced Buddhism to the region in the middle of the third century B.C.E. Subsequent invaders included Graeco-Bactrians from Afghanistan, Scythians from central Asia, and Parthians from Iran. Each conqueror left an imprint on the culture; the result was a cosmopolitan, multiethnic society with a sculptural tradition that mixed local styles and subjects with borrowings from Indian, Persian, and Hellenistic art.

In the mid-first century C.E., the Kushans, a nomadic tribe from Central Asia, gained control of Gandhara. Kanishka I, the third emperor of the Kushan dynasty, was a strong supporter of Buddhism who ruled from centers in Gandhara and Mathura in northern India. Buddhist art flourished in both places for the next several centuries—in Mathura, as streamlined, Indian-influenced carvings in pink sandstone; in Gandhara, as cruder, but more stylistically varied sculptures in hard gray schist or terracotta.

The first part of the exhibition traced some of the cultural influences at work in Gandharan art through a selection of sculptures incorporating Indian and Greco-Roman motifs. The earliest of these are marked by startling disjunctions and surprise appearances. The curling acanthus leaves on a Roman-style Corinthian capital shelter a tiny, seated buddha. Along the edge of a stele—pillar—carved with chapters from the Buddha’s career (including an episode in which he sternly reminds a barking dog of its previous life) are numerous pairs of cavorting Greek erotes—love gods. And a half column, used to demarcate a scene on a narrative relief, is similar to a type found in Iran, while the buxom female figure leaning against it is an Indianyakshini, or tree spirit.

The Kushan period saw several extraordinary developments in Buddhist iconography, including the depiction of the Buddha in human form (before that he was represented by symbols such as a footprint), as well as a renewed interest in stories of his life and the appearance of an ever-expanding cast of buddhas, bodhisattvas, and celestial deities. These artistic innovations coincided with, and reflected, the evolution of Mahayana Buddhist ideas, among them the emphasis on forging an individual relationship with the deity, the concept of the bodhisattva who reaches enlightenment but foregoes nirvana in order to help others, and the notion of multiple here-and now buddhas accessible to the practitioner through meditation and visualization.

As in India, the earliest figural images of the Buddha in Gandharan art most often appeared as part of the carved decorations on stupas—Buddhist reliquaries—and the next section of the show features a variety of architectural details from such monuments. Here, in lively reliefs depicting popular scenes from the life of the Buddha, the Gandharan artists can be seen beginning to consolidate their various influences.

In one particularly charming image Maya, Prince Siddhartha’s mother, smiles as she dreams of her unborn son in the form of an elephant encircled by a halo. Another relief depicts a phalanx of hair-raisingly realistic demons sent by Mara to distract Siddhartha from his meditations. Through such pictures, practitioners could follow the story of the Buddha and his spiritual journey and, by adhering to the same path of renunciation, meditation, and wisdom, likewise achieve enlightenment.

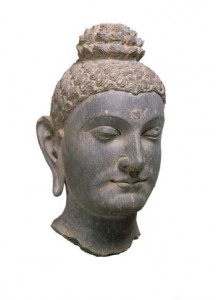

A range of types populates the show’s third section, which is devoted to images of buddhas and bodhisattvas. A muscular second-century bodhisattva in one corner conforms to western ideals of masculine beauty, while across the room, a less buff but dashingly bejeweled and mustached Maitreya, the future Buddha, represents the full flowering of the Gandharan figural style, in which idealized, film starlooks are allied with a naturalistic treatment of the body and its enveloping draperies.

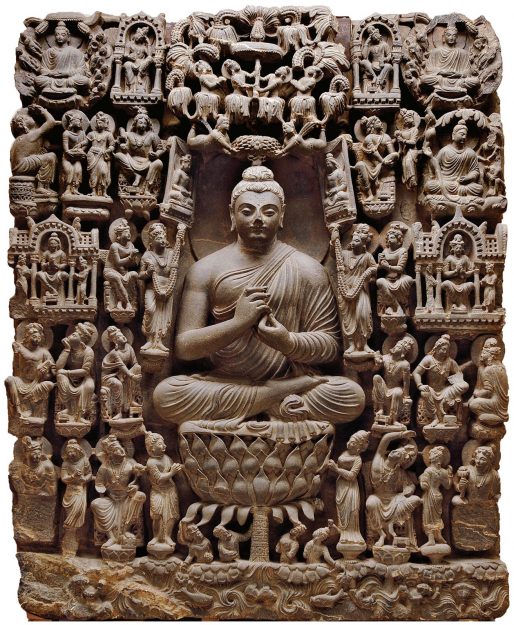

A highlight of the show is the so-called Mohammed Nari stele, which depicts a buddha sitting on a huge lotus surrounded by smaller bodhisattvas and worshippers. It may represent the Sukhavati paradise of Amitabha Buddha, or an unidentified buddha giving a teaching. In either case, as a representation of an enlightened being and his sphere of influence, it reflects a growing emphasis on the Mahayana doctrine of a transcendent buddhanature.

In Gandharan Buddhist art, dating is uncertain, messages are mixed, influences come and go, and works range from clumsy to sublime and from suave to kitschy. Looking at this show, which is full of gaps and cross-pollination, can be a little like trying to listen to a garbled radio transmission. But the overall impression is of vivid life and of a system of thought in development—one that would demand new visual languages and find one of them in Gandhara’s syncretic art.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.