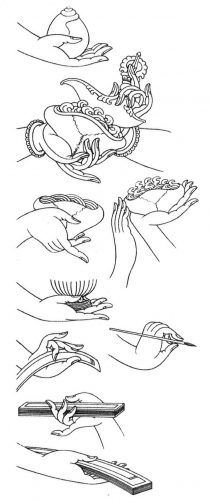

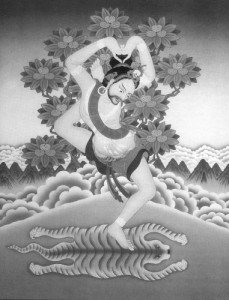

Born in South Wales in 1947, Robert Beer was drawn to painting and Buddhism as a child. After experimenting with psychedelics in his early twenties, he spent six years in India and Nepal, where he studied Buddhism and the art of Tibetan thangka painting. His paintings of Tibetan saints and adepts illustrate Buddhist Masters of Enchantment: The Lives and Legends of the Mahasiddhas (with translations of Tibetan texts by Keith Dowman; published by Inner Traditions in 1988 and 1998). This fall Shambhala Publications and Serindia Publications jointly will be bringing out The Encyclopedia of Tibetan Symbols and Motifs, with both text and illustrations by Robert Beer. An exhaustive compilation of the symbolism found throughout Tibetan art and ritual objects, The Encyclopedia itself has been ten years in the making, but represents Beer’s completion of thirty years of work and study. In May, Tricycle met with the artist at his thangka-filled flat in London as he was trying to finish up the introduction to the text. He had not slept or eaten for three days—which, according to friends, is not unusual. The line drawings are from The Encyclopedia. This book contains over 160 pages of brush and ink line drawings, with several thousand individual drawings of ritual implements, offerings, and symbols; on average, each illustrated page required around eighty hours.

How do you understand what it is that you do? Are you making art?

I’d say art makes me, rather than me making art. There has been a compulsion to do this work. It’s as if I have been driven and it has been my destiny to do this work.

Do you see your work as a practice as well?

Absolutely. The practice is being with yourself, with actually sitting down and being in that space. The whole of Buddhist art is an encapsulation of Buddhist teachings. So little by little one begins to understand what Buddhism is about through immersion in the content of the imagery and the activity of drawing or painting it. Yet in some way it becomes a personal understanding created through one’s own perception and intuition. There have always been different philosophical schools, but the understanding remains one’s own. So the art is a by-product of the experience of being with yourself, of living within patience. If you work alone for eighteen hours a day, then you have the continuity of exploring the mind for eighteen hours a day.

And is drawing in such a traditional form a way of inhabiting or embodying the teachings?

Yes. When I first became involved with Tibetan art it was as if I’d been suddenly projected into a land of incredible deities and images. And although there is no one there to tell you what they mean, it is very obvious that something really complex, some deep meaning, is behind them. It’s like you’re suddenly an explorer in Mongolia or Tibet. You’re just plunked down amid all these white areas, and you’ve got to make a map of the whole country to understand it. But the only way you can explore it is to go there. So you go, and bit by bit you learn that this area has a mountain range over here and a lake over that way. And then later on it all begins to interconnect, and you see the whole landscape evolving and then, like a fractal, it breaks up into the same things again and again and again. And Buddhism is like this – the depths of the conceptual reality go in and in to infinity, as if they arise as harmonics to a tonic note on increasingly higher octaves. Yet one has to use the same words to describe them. None of the concepts in Buddhism are fixed things. They’re all inspirational, all relative. You can’t define wisdom as “this” or compassion as “that.” There’s just this vast level of transformation within every Buddhist concept, which continually breaks open to reveal the same thing again and again, yet always with a deeper meaning.

In the illustrations for the Mahasiddhas book, departing from the traditional form is sometimes very obvious, like when you introduce a geometric style or get really psychedelic; but sometimes it’s much less obvious – say, when the airbrushing in the background gives the image a flatter surface. But clearly, personal choices informed these paintings. The line drawings suggest no – or relatively little – personal departure. There apparently is no departure, but this is not the case at all. Although the image is held very clearly in the mind, what’s reproduced on the paper is not the same, but you’re trying to get as close as you can to that original vision. Within Western art, because you don’t have the wealth of material that is transmitted through an ancient tradition, you’re working within the limits of your own imagination. Imagination is the key to an understanding of Tibetan Buddhist art. The visualization practices are the practice of expanding the imagination, which develops within the practitioner a greater understanding of these vast Buddhist concepts. In modern Western art the trend is to follow the cult of the personality, to be on the cutting edge of new concepts. Yet these new concepts are extremely limited in comparison to the richness of Tibetan art.

What makes traditional Tibetan art “good”?

When it’s iconographically correct. And it’s bad when it has iconographical mistakes.

Where is the liberation within the system for making this art?

It’s internal. It’s the liberation of the imagination. Sometimes you see the most incredible innovations that have been painted in a thangka. An artist may, for example, portray a group of offerings in a specific way that reveals the genius of innovation, a way that you’ve never seen or thought of before.

Do you ever have visions of works that are radically, let’s say, personalized?

I used to. They exist in my mind. I am able to clearly see them.

And you have no desire to make them?

Not any more. I used to. But there’s too little time. Some of these things that I wanted to make would take me a year, and I can’t give a year of my life anymore to an image when that image already exists within my imagination. It’s form and emptiness.

Did your Buddhist teachers encourage your art?

My main Tibetan teacher, Khamtrul Rinpoche, was a master artist. Once when I was halfway through one of the preliminary practices I became so furious that I threw the prostration board at the altar. Immediately after this “release” I felt a great peace and a deep humility. I went straight to the temple to tell Rinpoche how I felt and what I had just done. He laughed for a long time and then told me that it was better that I made painting my practice and not meditation, as obviously my heart was in the former. He then went on to tell of a practitioner in Tibet who felt he was too unripe for the tantric visualization practices and chose instead to dwell upon the four preliminary contemplations of suffering, impermanence, karma, and death, and eventually attained enlightenment through this practice. Painting was the perfect method of practicing these contemplations, and essentially this has been my practice. Rinpoche knew well the internal space of artistic creation, where the mind reveals itself and its content of agony and ecstasy, where there is nothing to do but watch the mind. He told me that my practice should be through painting, that this could be a method of self-purification like the Vajrasattva practice.

And that’s how you’ve been practicing since?

Yes, when you sit down, all that you’re exposed to is your own mind, there is nothing else. It’s no different really from being in retreat. I’m not trying to claim anything here. It’s just a natural process. You sit with your mind and in the beginning you don’t have much patience, and after years and years of doing this work patience begins to develop. Just to remain in that space and to let things arise and fade without having to grasp at them makes one realize that everything is already here, that no higher teaching is needed or to be grasped at. Things just come and go. It’s an endless process that goes on and on, and probably even after a thousand years it will keep going on like that.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.