Some folks sit on a cushion and count their breaths as though it were a matter of life and death. Others, like 68-year-old Jerry Roberts, a retired avalanche forecaster for the Colorado Avalanche Information Center, meditate wholeheartedly on the intricacies of snow.

I do not use that word “meditate” lightly. As a forecaster, Roberts’s job was to rigorously and relentlessly observe the snowpack. That involved studying everything from weather systems swirling in the Pacific to the structure of ice crystals out the back door. His special awareness was then tapped by the Colorado Department of Transportation to help determine when to shut down the mountain roads around Telluride and Durango. Winter in the San Juan Mountains begins in October and ends in June, and the range often receives 300 inches of snow in a single season. It is a notoriously dangerous place.

Currently, Roberts does part-time consulting work with Mountain Weather Masters, an outfit he cofounded. The group’s logo—a sword-wielding samurai backed by a white cloud—reflects his longtime interest in Japanese culture. Roberts’s house in Ridgway, Colorado, is cluttered equally with avalanche maps and anthologies of haiku by Issa, Buson, and Basho. I met him there on a bright winter morning, and we sat by the fireplace, drank coffee, and talked. He showed me homemade chapbooks of his own free-verse haiku, many of which braid the languages of snow science, skiing, and mountain geography with the language of Zen.

Enlightenment? Roberts wouldn’t claim to know much about such an exalted state of being. Self-deprecating and quick to laugh, he jokingly referred to our conversation as “bullshitting.” Nevertheless, I could tell from his warmth and sincerity that talking about snow and poetry was, for him, an immensely valuable pastime. After my second cup of coffee, when I rose to leave, instead of offering a handshake, he smiled and told me, “Keep on enjoying life.”

–Leath Tonino

How did you first get interested in snow and avalanches? Living inside was never an option for me. I grew up at the foot of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains, here in Colorado, and as a kid I was constantly outdoors. A big part of my life was climbing peaks and skiing off them. Digging nature. Enjoying the turn. Feeling the wind on my face. Those experiences in the wild can be so vivid. You become them. For some of us, there’s no turning back.

Spending so much time in the backcountry, sometimes going out for weeks on end, I saw my share of avalanches. Pretty soon I was thinking, Hmm, I better learn a bit about this huge power I’m edging up against. The air blast created by an avalanche can reach 200 miles per hour. In some cases we’re talking hundreds of thousands of cubic yards of snow on the move.

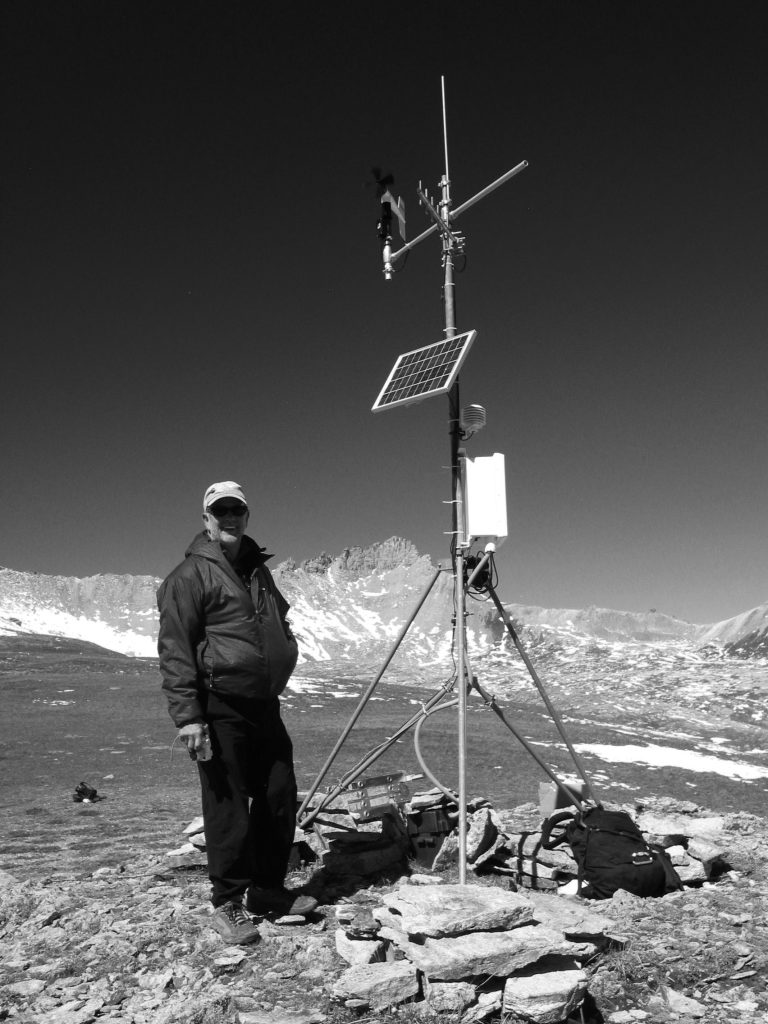

So in the early seventies I found my way to the San Juans and took an avalanche course. Within a few years I’d moved into an abandoned miner’s cabin in the subalpine and was collecting data for the Institute of Arctic and Alpine Research. It was a simplified, almost ascetic existence—skiing a bunch, learning the snowpack. The locals down in town called me and another buddy who lived up there “the snow monks.” We were hooked. Who would have ever thought looking at snow could be so exciting?

What exactly does “looking at snow” entail? It all starts with the weather. Back then, forecasters weren’t using the Internet. What Internet? It was more like a finger in the air: Okay, it’s coming from the southwest. Might be a big one. Get ready.

Wind is the architect of avalanches, so you’re tracking the storm’s movements, gauging speed and direction. You’re monitoring temperatures, too. Did the storm come in warm and then cool down, bonding the new snow to the old snowpack’s surface? Or did it come in cold and then warm up, creating a dangerous upside-down cake, a heavy, wet slab sitting atop a low-density base? You’re constantly interpreting. Is it a hard block or a soft block? What got loaded with snow, north faces or northeast faces?

Small world becomes big world—that’s how I like to sum it up. A forecaster observes things at two scales, the micro and the macro. You look at a snow crystal under a hand lens and see all the beautiful angles, and then you think about how a hillside loaded with these things can all of a sudden fracture, come down and cover the highway, and sweep you into oblivion.

I’m reminded of a line from the Soto Zen teacher Taisen Deshimaru: “You must pay attention as if you had a fire burning in your hair.” Yeah, you’re afraid to go shopping at the supermarket an hour away because you might miss a wind event. You can’t be absent from your place. You have to be totally present.

Forecasting is not just a job; it’s a lifestyle. You don’t think about Christmas or your wife’s birthday. You don’t go on vacation. One storm in ’05 lasted four days, and I got maybe eight hours of sleep. From November through May, paying attention is what you do. It’s who you are. There’s no difference between on and off.

Over the years, I learned so much by just being out there. A friend of mine says, “Experience is a series of nonfatal errors.” Every winter I added something new to the list of what I knew. You develop a daily mantra, your daily prayers: Look for this, note this, pay attention to this. If you don’t, somebody is going to get hurt. Maybe you.

As you immerse yourself in the observation of these massive forces—storms and avalanches and the like—you must become increasingly aware of your own smallness, your own fragility. There’s a quote attributed to Miles Davis that says, “If you’re not nervous, you’re not paying attention.” I used to joke that it was my job to worry for half the year. That sounds negative, but it’s not. The worry is itself a kind of meditation. You worry from the first storm to the last storm. Why hasn’t that slope avalanched? It’s got to avalanche soon.

Our mortality is with us through all stages of life, whether we’re aware of it or not. As a snow viewer, out in the middle of the storm, you know that the possibility of the end is always present. Mortality isn’t an abstract concept—it’s right in your face. The sky is falling! How am I going to get home without being killed?

At times it was dangerous driving the road in “full conditions,” snow coming down so hard you could barely see past the steering wheel. Over the years, small avalanches took me for some rides while I was out skiing. For much of my life I’ve had a daily, maybe an hourly appreciation of my own impermanence—a heightened sense of how delicate things really are.

Because no matter how much expertise you have, no matter how keen your focus and diligence are, the big one can still slide on you unexpectedly, right? One has to be comfortable living with uncertainties—that’s just part of the deal. In the worlds of snow and weather, but also in the rest of life, there are so many unknowns. Our job is to try to reduce some of the uncertainties while simultaneously learning to live with them. Some days are better than others, and every day is another invitation to try.

Without mindfulness, my job living with the uncertain nature of snow would have been impossible. Sitting, walking, skiing, they all lead to the same place: Mindfulness. Mindfulness of what is.

How does haiku fit into all of this? I’ve always been drawn to the counterculture, so naturally I spent some time in the Bay Area in the sixties. I was interacting with the Beat poets, going to readings at bookstores. That was my first eye-opener. All of a sudden I was thinking on that plane—the haiku plane.

The Zen aesthetic relies on the fewest possible words to express a situation, a feeling, a view. It shaped how I looked at everything, including snow. Alongside the more scientific approach to the snowpack, I began to understand it through these little descriptive bursts: “Wind slab layers / thick as Van Gogh / brush stroke.” I’d pull off the road during a blizzard, or stop at the end of a ski run, and scribble something about the mood in my notebook. Some of my haiku are okay, some aren’t. That’s fine with me. The importance lies in the attempt, the effort at catching a moment.

The poet Jorie Graham has described poetry as a way of going through life, as opposed to accidentally slipping around it. Even if you’re serious about not going around it, you do. We all do. Searching for the right words to make a haiku, skiing a perfect line through the trees—these can get you going through life, at least for a little while.

The haiku is both a meditation and an expression. You disregard the nonessential and focus on the essential. There’s a discipline to it. It’s similar to writing a good avalanche forecast or weather forecast with a minimum of words—less room for confusion or misinterpretation. It’s also an attempt to share some space with the masters, to walk the mountain paths with traveling monks and roshis, begging bowl in hand. There’s a haiku by Basho that I love: “Come, let’s go / snow-viewing / till we’re buried.”

Buried in what? In snow? I wonder if it isn’t also something else. As you put it a minute ago, maybe by viewing snow we get buried in “what is.” One of the great things about snow is that its meanings are infinite. It melts and becomes ditchwater for ranchers or drinking water for city dwellers. It has significance for an avalanche forecaster today and for Basho back in the 17th century. It can be a dream or a nightmare. And yet it’s all the same, just different crystals that have bonded together—needles, columns, stellars.

After six-plus decades in the Colorado Rockies, what would you say are the lessons that stand out in your mind? It might sound trite, but what I’ve learned is that the mountain always leads in the dance. It’s hard to say much more about it than that. You do what you are allowed, nothing more. You wander around above the trees, knowing all the while that you are a temporary trespasser.

I don’t want to be a downer, but people are going to die. Avalanches will take us out. It will happen. Years ago, a friend said to me that in the San Juans we’ve got a “tiger of a snowpack.” That always stuck with me because of its animistic sensibility. Rocks, snowfields, clouds—I see them as alive. That mountain outside the window is a living, breathing thing. And it’s bigger than you are! It’s in charge. If you’re not careful, you’re going to get bit in the ass by the tiger. You’re going to suffer. It’s a big tiger.

As you said earlier, though, for some folks there’s no turning back. It’s a risk worth taking. Right, so you learn all you can, pay attention, and then learn some more. Nature has this draw, whether it’s the ocean, the desert, the river, or the mountain. For me, it’s the sound of wind from Arizona and Utah carrying desert dust that will become the snowflake nuclei here in the San Juans. It’s that smell: “Aaaaaah, the turn / I can smell it / in the air.” It’s the feel of powder snow blowing up into your chest as you round your turn on a beautifully angled slope. There’s stillness at the heart of that motion. Gravity is pulling you down, the same force that wants to collapse the entire snowpack and send it to the valley floor. Steep skiing is just one controlled fall after another.

“One controlled fall after another.” That has a lot of overtones. Words come up short. D. T. Suzuki, the prominent early exponent of Zen in the West, once said, “When a feeling reaches its highest pitch, we remain silent, even 17 syllables may be too many.”

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.