The architect of the Indian constitution. The drafter of the Hindu Code Bill, which permitted Indians from different castes to marry and extended equal rights to men and women. The man who believed Buddhism was the only way to liberation, leading hundreds of thousands of Dalits (“untouchables”) to convert to Buddhism and escape the oppression of the caste system. What Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar (1891–1956) achieved was in many ways unthinkable given the tremendous discrimination he faced as a young Dalit. But, had Ambedkar not met and married a young doctor named Sharada Kabir, it’s unlikely that he would have been able to accomplish nearly as much as he did during the last decade of his life.

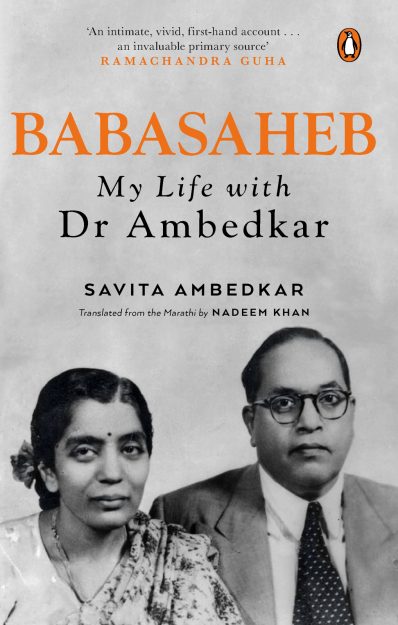

Babasaheb: My Life With Dr Ambedkar

By Savita Ambedkar, translated by Nadeem Khan

Vintage Books, April 2023, 368 pp., $27.99, hardcover

Kabir, who became known as Dr. Savita Ambedkar after their marriage in 1948, published her memoir in the Marathi language in 1990. In 2022, nearly twenty years after her death, Babasaheb: My Life with Dr Ambedkar was published in English for the first time. Translated by Nadeem Khan, Babasaheb gives English speakers an insightful look into Savita’s complicated commitment to serving her husband—whom many consider a bodhisattva—as a companion, caretaker, and trustworthy confidante during watershed moments in modern Indian history.

Savita was born in 1909 to what she described as a progressive Brahmin family. Graduating with a bachelor of medicine and surgery from Grant Medical College in 1937, Savita worked as a junior doctor for Dr. Madhavrao Malvankar in Mumbai before accepting a position as chief medical officer of a women’s government hospital in Gujarat. But facing some health issues, she returned to Mumbai and resumed her work with Malvankar.

Enter B. R. Ambedkar. Savita writes that she wasn’t familiar with him before meeting him at a friend’s house. He was “deeply concerned about women’s progress” and congratulated the young doctor on her accomplishments, Savita Ambedkar writes; they also discussed Buddhism in their early meetings, leaving her “literally goggle-eyed with wonder.”

Though Ambedkar had the elegance of a German prince and the stamina of a high-ranking politician, he was suffering from a number of significant health issues (including diabetes, rheumatism, high blood pressure, and neuritis), which were put on the back burner while he worked on the constitution in 18- to 20-hour stretches. He sought the medical advice of Dr. Malvankar, whom Savita Ambedkar worked with as a junior doctor.

The Ambedkars’ marriage started as more of a medical commitment than a romance: Savita had offered to live with him to oversee his treatment, diet, and rest; Ambedkar instead proposed, in part because “for the sake of millions of my people, I have to live on.”

“His personality, his work, his sacrifice, his scholarship, they were all mightier than the Himalayas. Placed against his lofty personality, I was an utterly shrunken phenomenon. How was one to turn down a great person like Dr. Ambedkar?” Savita writes. “The doctor inside me was prodding me to go and serve him medically. The government had placed upon his shoulders the historic responsibility of drafting the Constitution of free India, and therefore it was utterly imperative that his health should be well looked after, and he should be given appropriate treatment.”

She accepted, and they were married on April 15, 1948, less than three months after Gandhi was assassinated. “From then on till the last moment I stayed with him ceaselessly like his shadow,” she writes.

“Placed against his lofty personality, I was an utterly shrunken phenomenon.”

Over the past several years, I’ve had a number of conversations with a dharma friend about the faults of applying modern thinking to the lives of ancient Buddhist women. She is working on a book about the Buddha’s birth mother and views Mayadevi as the goddess she is; to compare her to an earthly woman makes no sense, because she was divinely chosen to be the Buddha’s mother. We can take inspiration from her qualities, but to try to think of her as a woman in our world is futile.

In that sense, it was more comfortable for me to think about Savita Ambedkar’s life as a dharma story rather than the biography of a modern woman. When I begin viewing her life through a feminist lens, I see only what she gave up to be the “shadow,” the constant companion and caretaker of one of the most important men of independent India.

The few glimpses we get of Savita are inspiring and fierce: when Ambedkar was so ill that his constant stream of visitors would not help his condition improve, Savita cut meetings short, or refused to let them start in the first place, so that he could rest. Although they employed a cook, Savita would prepare his food with healing in mind; she taught him yoga asanas and made sure he had oil massages to help with circulation. Savita kept Ambedkar on a strict schedule, helped bathe and dress him; Savita made it possible for him to read and write into the night and work on legislation that affected millions of people at the time (and all the generations to come). Indeed, the ink was still drying on edits and corrections to The Buddha and His Dhamma when Ambedkar died in his sleep on December 6, 1956.

Yet following Ambedkar’s death, Savita was forced into obscurity. Some of Ambedkar’s followers even alleged that she had murdered him, and a significant amount of the memoir is spent establishing Ambedkar’s health history and how she likely prolonged his life. Though she was effectively blocked from politics, Savita found friends among the younger generation of social reformers in the seventies and eighties, garnering respect from the Dalit Panthers, radical anticaste thinkers who were inspired by Ambedkar, Karl Marx, Buddhism, and groups like the Black Panthers in the US.

Early on in the book, Savita compares herself to Yashodhara, the Buddha’s wife. Like Yashodhara, about whom we know little from Buddhist literature, Savita’s innermost thoughts and dreams remain a mystery. We are instead left wondering what we might do if a bodhisattva came into our lives. Would we set aside everything to serve them too?

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.