I was in college in the 1970s, already a diehard Beatles fan, when I first heard rumors of what seemed impossible: a Beatles album that was even better than the White Album or Abbey Road—a record that, although successful when released in the 1960s, had been eclipsed by the band’s subsequent achievements and never received its rightful due. I ordered mine from England to be sure of getting the correct version—and before I knew it, I ended up like countless others before me, sitting in a darkened room, listening over and over to “Tomorrow Never Knows,” and trying to figure out how to meditate.

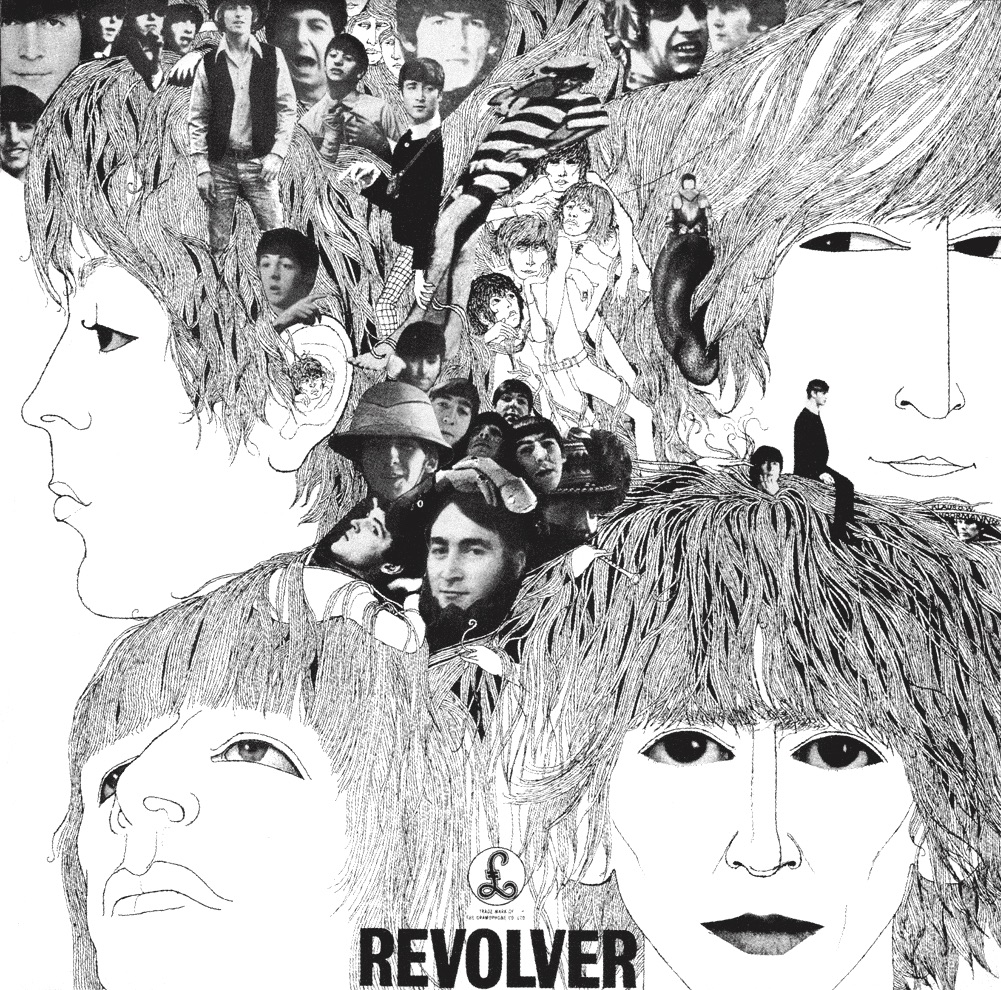

The year 2006 marks the fortieth anniversary of that album: Revolver—the first presentation of the Beatles’ fascination with Eastern mysticism and its possibilities for the Western mind. Eastern philosophy had been popular in certain circles since the 1950s, but it wasn’t until the mid-60s that it began to break into the mainstream, triggered in part by Revolver’s intimations of “another road where maybe I could see another kind of mind there.”

Although it was long overshadowed by the following year’s Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, many listeners regard Revolver as the deeper, more serious album. Compared with the highly ornamented, self-conscious Pepper, Revolver seems down to earth, gritty, real—yet it already displays many of the innovations for which Sgt. Pepper would later be acclaimed. It has arguably aged better than its flashier sibling; and in two major end-of- the-century surveys, by Virgin Records and VH1, it surpassed Pepper as the greatest album of all time.

Released August 5, 1966, Revolver introduced an entirely new sonic palette to rock ’n’ roll, exploding then-current notions of what pop music was and could be. Notable were the first of George Harrison’s raga-influenced sitar compositions—which some observers point to as the birth of “World Music”—as well as backward guitar solos, tape loops, psychedelic sound effects, and other innovations that would change recording forever. As the Beatles’ first album-length attempt to deal with subject matter beyond romantic love, Revolver can also be regarded as their first “concept” album because of the network of closely linked themes that run through it. (Lennon later denied that Revolver was a concept album, but he said the same thing about 1967’s Sgt. Pepper!)

Revolver stands as perhaps the most pivotal recording in the Beatles’ career, marking their transition from teenage heartthrobs to social commentators, visionaries, and spokesmen of a generation. The album also ended the era of Beatles songs that could be reproduced in concert, signaling the entry into their “Studio Period,” where their creations would become dependent on the use of sophisticated production techniques. After 1966 they would never tour as a group again.

How could it be that the same band that had won worldwide fame in 1963 for singing “She loves you, yeah, yeah, yeah” could have produced such a musically sophisticated, acclaimed masterpiece as Revolver a mere three years later?

As it turned out, they had a little help from their friends. Bob Dylan turned the Beatles on to marijuana in 1964, and shortly thereafter Lennon and Harrison were slipped LSD without their knowledge at a dinner party. Both found the experience terrifying, but saw enough potential to merit further experimentation.

“Soon,” Lennon told Rolling Stone in 1971, “I was popping it all the time.” Motivated by these experiences, Lennon became interested in Buddhism, particularly Timothy Leary’s adaptation of the Tibetan Book of the Dead. Retitled The Psychedelic Experience, Leary’s interpretation presented the Tibetan text’s death references as pointing to death of ego—in other words, enlightenment (in Leary’s view, a condition achievable through the shortcut of LSD).

“What I’m interested in is Nirvana, the Buddhist heaven,” Lennon reported in an interview shortly after Revolver’s release. Harrison, who had meanwhile become deeply involved with Hinduism, later said that “until LSD, I never realized that there was anything beyond this state of consciousness. . . . There was no way back to what I was before.”

Lennon later claimed to have taken a thousand trips in an attempt to extinguish his ego. The drugs first opened his mind, and then, by his own account, clouded it—but Revolver came at the height of the expansive phase, when anything seemed possible. McCartney and Starr were soon to follow in their bandmates’ psychedelic footsteps; but despite the pharmacological influence, the Beatles’ quest was real, and they explored it not only through drugs but also through study, meditation, and yoga. McCartney even built a “contemplation dome” in his backyard.

The world around them seemed obsessed with power, appearances, and material goods—all of which they themselves had achieved and found lacking. Lennon, who was at this point still functioning (if a trifle uneasily) as the group’s de facto leader and resident visionary, had recently tried on the role of social prophet with Rubber Soul’s “The Word”:

Say the word and you’ll be free

Say the word and be like me

. . .

Now that I know what I feel must be right I’m here to show everybody the light

The role seemed to suit him. As their minds opened, the band felt a natural impulse to share what they’d discovered. The world certainly looked like it could use some help, and with a new album in the works, they had the means to provide it.

Still, at this point the four could hardly have dreamed of the impact the new direction they were taking would have not only on the musical world but also on society and culture at large. Innovations abound: Revolver boasted the broadest soundscape of any rock record to date, with instrumentation ranging from French horn to sitar and tablas, from soul-inflected brass and string quartets to the undersea sound effects of the children’s singalong “Yellow Submarine”—combining to create the perfect sonic backdrop to its themes of expanded consciousness. All this while never losing sight, with songs like “Taxman” and “Dr. Robert,” that this was still rock ’n’ roll.

Revolver’s importance, however, was not as immediately apparent as it might have been in America, for the peculiar reason that U.S. listeners were not hearing the entire record. This was due to the American company practice of trimming a few songs from each LP and combining them with singles until they had enough for an extra album. Missing from the U.S. version were Lennon’s “I’m Only Sleeping,” “And Your Bird Can Sing,” and “Dr. Robert,” making the album’s unity less than clear.

The Beatles had ignored this in the past, but now the alterations seriously impacted the structure and message of the work. When a request came to provide a cover shot for Yesterday and Today—a record composed entirely of such “borrowed” songs—the boys sent back a photo of themselves in butcher’s coats, surrounded by hunks of meat and decapitated baby dolls. Capitol obediently issued the cover, only to recall it immediately after public outcry. The sleeves were eventually papered over with a more acceptable image and re-released, but the point had been made: never again would an original Beatles album be “butchered” by an American company. The deletions from Revolver were corrected on later CD releases, contributing to the album’s current reputation. Still, an original “Butcher Cover” of Yesterday and Today remains among the most collectible Beatles artifacts.

Revolver’s song sequence can be seen as a progression of states of consciousness, from the earthly, alienated world of “Taxman” and “Eleanor Rigby” to the possibility of transcendence offered by “Tomorrow Never Knows.” How much of this unity was intentional remains open to question. Lennon himself commented during a 1968 Rolling Stone interview: “We write lyrics, and . . . don’t realize what they mean till after. Especially some of the better songs . . . [like] ‘Tomorrow Never Knows.’”

When the interviewer commented that critics often read something into a song that isn’t there, John responded: “It is there. It’s like abstract art. . . . It’s a continuous flow . . . just pure, and that’s what we’re looking for all the time, really.”

“Tomorrow Never Knows,” at once the most extraordinary, most experimental, and purely artistic creation the Beatles had yet produced, is the album’s Rosetta stone.

From the first cuts, Harrison’s “Taxman” and McCartney’s “Eleanor Rigby,” the Beatles clearly signal their expanding intentions. The self-conscious coughs and studio chatter of the album’s opening break the separation between musicians and audience and set in motion a performance that unfolds song by song before us—a concept they would take yet further with Sgt. Pepper. Meanwhile, their lyrical concerns now included everyone from greedy politicians to “all the lonely people.”

But it is with Lennon’s “I’m Only Sleeping” that we realize this is different from any pop record that came before. With its dreamy, swirling tape effects, this cut is generally seen as an homage to the joys of staying in bed all day or an evocation of drug-induced dream states. Yet isn’t Lennon speaking for the entire straight-laced world, living like poor Eleanor Rigby “in a dream” of falsity, alienation, and materialism, as he pleads: “Please don’t wake me, no don’t shake me, leave me where I am, I’m only sleeping.”?

But it is with Lennon’s “I’m Only Sleeping” that we realize this is different from any pop record that came before. With its dreamy, swirling tape effects, this cut is generally seen as an homage to the joys of staying in bed all day or an evocation of drug-induced dream states. Yet isn’t Lennon speaking for the entire straight-laced world, living like poor Eleanor Rigby “in a dream” of falsity, alienation, and materialism, as he pleads: “Please don’t wake me, no don’t shake me, leave me where I am, I’m only sleeping.”?

The final song on the LP’s Side One (a distinction lost in the CD era) must have come as the most terrific shock yet to fans who thought they’d merely purchased another record by the Four Loveable Moptops. “She said, I know what it’s like to be dead.” Lennon’s disquieting lyrics arise from the opening riff of “She Said, She Said” with a strangeness that seems inescapable even today. Communicating simultaneously the loss of innocence and the transcendence of visionary experience, the words came from a phrase actor Peter Fonda repeated during John’s first intentional acid trip, causing the Beatle considerable paranoia. Here Lennon transforms that experience into his first presentation of an alternate kind of death—ego-transcendence.

With its three closing songs, Revolver finally completes its progression to a state of greater awakening. Harrison’s “I Want to Tell You,” with its Eastern musical overtones and hypnotic piano, eloquently expresses the singer’s frustration at communicating, as George put it, “the avalanche of thoughts that are so hard to write down or say or transmit,” while McCartney’s soul-inflected “Got to Get You Into My Life” transforms the quest for love into longing for greater vision:

With its three closing songs, Revolver finally completes its progression to a state of greater awakening. Harrison’s “I Want to Tell You,” with its Eastern musical overtones and hypnotic piano, eloquently expresses the singer’s frustration at communicating, as George put it, “the avalanche of thoughts that are so hard to write down or say or transmit,” while McCartney’s soul-inflected “Got to Get You Into My Life” transforms the quest for love into longing for greater vision:

I was alone, I took a ride, I didn’t know what I would find there

Another road where maybe I could see another kind of

mind there

But it’s the last song that provides the finale of finales. A sitar-like drone arises as though from nowhere, followed by a primal, thudding drumbeat, while what sounds like some species of prehistoric bird floats above. What must certainly have been the most peculiar lyrics yet to grace a pop album rise out of the mix, delivered by Lennon in a chant-like vocal that seems to come from the end of a tunnel:

Turn off your mind, relax and float down stream

It is not dying, it is not dying

Lay down all thoughts, surrender to the void,

It is shining, it is shining

The lyrics, though they seemed obscure at the time, are basically a set of instructions for meditation practice, accompanied by the reassurance that this is not physical “death” the singer is talking about, but the attainment of a greater vision:

That love is all and love is everyone

It is knowing, it is knowing

And ignorance and hate may mourn the dead

It is believing, it is believing

“The whole universe is a wheel, right?” Lennon would say in a 1980 interview, shortly before his death. Certainly Revolver is a wheel—and “Tomorrow Never Knows,” the most extraordinary, most experimental, and purely artistic creation the Beatles had yet produced, is the album’s Rosetta stone, completing the circle. Although it appears last, this song was recorded first, setting the tone for the whole work—and with its lines lifted from the Tibetan Book of the Dead, it ties the album’s themes together, clarifying the entire concept. Lennon’s original idea called for a sonic background of “a thousand monks chanting.” Although this proved impractical, the actual result is perhaps more extraordinary still: a sonic collage orchestrated by George Martin and engineer Geoff Emerick, using tape loops that stretched out the studio door and down the hallway, with Lennon’s eerie vocal processed through a revolving Leslie speaker.

“Tomorrow Never Knows” is where Lennon most clearly reveals Revolver’s true subject as the attainment of higher consciousness. Having exhorted us to let go of thought, to surrender to the absolute, to realize oneness through universal love and join the “dead” who have abandoned their egos, the song’s long fadeout begins: “Play the game ‘Existence’ to the end/ Of the beginning, of the beginning . . .” The mantra-like repetition suggests death followed by rebirth until the ego dies at last and for all and “ignorance and hate may mourn the dead.” There had never been a pop song like it, and pop would never be the same. It sounds as fresh and startling today as it did when it was recorded.

“Tomorrow Never Knows” is where Lennon most clearly reveals Revolver’s true subject as the attainment of higher consciousness. Having exhorted us to let go of thought, to surrender to the absolute, to realize oneness through universal love and join the “dead” who have abandoned their egos, the song’s long fadeout begins: “Play the game ‘Existence’ to the end/ Of the beginning, of the beginning . . .” The mantra-like repetition suggests death followed by rebirth until the ego dies at last and for all and “ignorance and hate may mourn the dead.” There had never been a pop song like it, and pop would never be the same. It sounds as fresh and startling today as it did when it was recorded.

If terms such as “the void” and “ego death” seem a bit dated today, if Revolver’s presentation of mind-liberation was something the Beatles themselves were not yet able to fully manifest, there’s no doubt they put countless people on the path to practice, including this writer. What remains timeless is to hear Lennon, McCartney, Harrison, and Starr reinventing the sound, content, and purpose of popular music—and with it, themselves. Revolver stands as a document of an extraordinary moment when the possibilities of pop—and life—seemed boundless.

The group’s Maharishi period was yet to come, and although Lennon later became disenchanted with all organized religion, he continued to meditate off and on, and revisited Eastern themes well into his solo career. “I’ve never claimed to have the answer to life,” said Lennon in 1980. “I only put out songs and answer questions as honestly as I can. . . . I have found out personally that I am responsible. . . . There’s no separation; we’re all one.”

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.