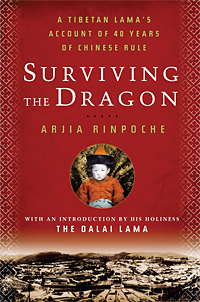

Surviving the Dragon: A Recent History of Tibet through the Looking-Glass of a Tibetan Lama

by Arjia Rinpoche

New York, Rodale Books, 2010

288 pp., $24.99 hardcover

By now, many of us have read the moving testimony of Tibetan monks like Palden Gyatso, who have had to endure decades of imprisonment and torture under Chinese rule. And thanks to the voices of writers like Thubten Samphel and Tenzin Tsundue, we are starting to learn about the confusions and sorrows of exiled Tibetans who have spent half a century dreaming of a place that can no longer be the home they imagine. Even the Fourteenth Dalai Lama has twice turned his life into a blend of unabashedly human reminiscence and acute political and historical analysis to create a parable with global implications.

By now, many of us have read the moving testimony of Tibetan monks like Palden Gyatso, who have had to endure decades of imprisonment and torture under Chinese rule. And thanks to the voices of writers like Thubten Samphel and Tenzin Tsundue, we are starting to learn about the confusions and sorrows of exiled Tibetans who have spent half a century dreaming of a place that can no longer be the home they imagine. Even the Fourteenth Dalai Lama has twice turned his life into a blend of unabashedly human reminiscence and acute political and historical analysis to create a parable with global implications.

But the unique power of “Surviving the Dragon”—a deeply engaging account of the last sixty years of Tibetan history, written without rancor—is that its author spent most of those decades at the heart (and sometimes near the head) of Communist China, working to protect the dharma from within. Arjia Rinpoche is the rare high lama who can write personal letters to the Chinese president, Jiang Zemin (and get answers back); who witnessed the installation of the Chinese-selected Eleventh Panchen Lama in a secret 3 a.m. ceremony at Lhasa’s Jokhang Temple; and who ultimately fled his privileged position disguised in sunglasses, a hat, and a new mustache. Yet beyond the invaluable historical testimony he offers, he launches a much more universal inquiry into what right action and right view really mean, and how we might begin to work withsamsara [cyclic existence] without becoming its captive.

The outlines of his story play like a Hollywood fairy tale, with thorns. Yong Drung Dorje was found by a monastic search party before he was two years old, and was declared to be the eighth recorded Arjia Rinpoche, the reincarnation of Tsongkhapa’s father and therefore the hereditary abbot of Kumbum Monastery. Shortly thereafter, he left the yurt where his large Mongolian family lived—near the great salt lake of Dolon Nor—and came to the monastery to begin his Buddhist training. But six years later, in 1958, the Great Leap Forward broke in on the little boy’s studies; overnight, it seemed, elderly rinpoches were being beaten by fellow monks sympathetic to Beijing, and one out of every six among Kumbum’s three-thousand monks were being arrested.

Four years of famine followed, and then, when Arjia Rinpoche was a teenager, he saw the Red Guards storm his temple and join sympathetic monks in smashing buddhas and burning texts while other monks wailed. Then, after fifteen years of working in the fields, he heard that Buddhism was notionally restored; the same lamas who had been humiliated for decades by their rulers were told that they had been innocent all along and should start rebuilding their temples.

It was the curious karma of Arjia Rinpoche to be able to ride this accelerated roller coaster while being spared outright brutality and imprisonment. In fact, in many ways he was fortunate: His uncle, Gyayak Rinpoche, had been the Tenth Panchen Lama’s tutor, and the then twelve-year-old Arjia Rinpoche and a young friend, Serdok Rinpoche, had had the opportunity to travel with the Panchen Lama to Lhasa. In “Surviving the Dragon,” he offers us indelible scenes of the young Panchen Lama speeding up in a jeep and adjusting his fedora as he gets out, and later putting on goggles and gunning the engine of his Russian motorbike, with the two excited young rinpoches seated in his sidecar.

Through many of these years, Arjia Rinpoche used his contacts and influence to try to raise funds for Tibetan projects and to protect ancient treasures, striving to support the dharma even if he could not formally practice it. It was only in 1998, when he was asked to be the new, Chinese-installed Eleventh Panchen Lama’s tutor, that he realized he could no longer work with the system, and escaped to the U.S.

What is remarkable throughout his story is that Arjia Rinpoche refuses to pass judgment on almost anyone but himself. Though he presents himself always as a poor student and a bad monk, he sees the whole drama as a lesson in impermanence, delusion, and shortsightedness. It is as if the “Wheel of Life” game that Tibetans played around him when he was young had now become life itself: One day he and his fellow lamas are made to watch monks being forced to drink urine; the next day they are told they should put on their robes again. One day “Deputy Chairman Arjia” is being feted as the equivalent of a deputy governor of a Chinese province; the next, as yesterday’s orthodoxy becomes today’s heresy, he is seeing other high-ranking Tibetans stripped of all their power. Everything is constantly a-tremble, and even those in power are daily in danger of humiliation.

The book becomes, therefore, a vividly tense, nuanced, and unflinching look at how to walk the Middle Way, not in theory but in agonized practice. For forty years, Arjia Rinpoche tries not to betray himself and his deepest commitments by supporting those who are attacking Tibet and its tradition of Buddhism, and at the same time tries not to endanger his freedom to help both, by too openly opposing Beijing.

His account of walking this constantly shifting tightrope is striking in its candor. Arjia Rinpoche goes out of his way to point out how many Chinese individuals were kind to Tibetans and sympathetic to Buddhism (one is even described as having a secret meditation chamber tucked behind his bed); and he notes openly how many Tibetan monks were involved in fighting, drinking, and even selling weapons and narcotics long before the Communists came along, making it possible for Beijing to tarnish all monks with the example of a few. He admits that at times he became “proud of his position,” and when he observes, close up, the Tenth Panchen Lama’s wedding— unsure if the lama is being forced to break his vows or wants to do so—he wonders whether all of them were “suffering from a sort of mass Stockholm syndrome.” When the opportunity to restore Kumbum Monastery arises, however, Arjia Rinpoche acts with authority and wisdom, founding a monastic school based on the modern principles outlined by both the Tenth Panchen Lama and the current Dalai Lama.

Yet it is integral to his story that there are no shortcuts or guaranteed happy endings, in his or any life. After finally escaping from China—no simple task for a lama under close surveillance, with no money or prospects at the other end—Arjia Rinpoche arrives at last in New York, and the Dalai Lama reminds him that, as the highest lama to defect since 1959, he should lie low and do nothing to jeopardize the ongoing talks between exiled Tibet and Beijing. Thanks to the efforts of American friends, he finally sets up the Tibetan Center for Compassion and Wisdom in Mill Valley, California (one of his first students is a fireman he meets in Circuit City), and relishes the chance for quiet study at last. But then a call comes from the Office of Tibet in New York, asking him to take over the Tibetan Cultural Center in Bloomington, Indiana, long run by the Dalai Lama’s eldest brother, Taktser Rinpoche. He politely says no. Another call comes, and he says no again. Finally he is told that the Dalai Lama himself wants him to take over the center from his ailing brother. He leaves his peaceful life and heads for Bloomington.

Many of us have heard about the practice of treating an enemy as a friend by drawing a circle of “we” so wide that no “they” exists any longer. But it’s humbling to see these precepts put into practice in such cruel circumstances. At one point, Arjia Rinpoche’s beloved tutor dies, and his students have to perform a seven-day burial ritual for him in secret. Then the staunch friend who has protected Arjia Rinpoche for years in the monastery suffers a stroke, and he dies, too. As the Red Guards attack, Arjia Rinpoche heads out to his family’s yurt, and his mother and siblings tell him that his father has been taken away to a prison camp, and is presumed dead. Arjia Rinpoche records all this calmly, though every now and then (as when his mother dies), he admits that he couldn’t hold back his tears. “Surviving the Dragon” is a heart-shaking illustration of what one of Arjia Rinpoche’s teachers once told him: Social status is “a piece of paper, with little weight, easily blown away.” Compassion is a “piece of gold.”

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.