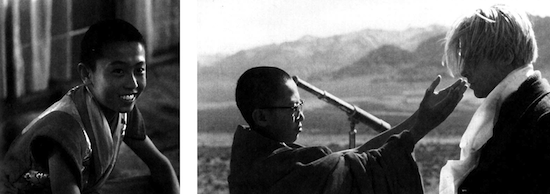

In researching the script for Seven Years in Tibet, the film version of Austrian mountaineer Heinrich Harrer’s memoir, screenwriter Becky Johnston discovered her own passion for Tibetan Buddhism. Directed by Jean-Jacques Annaud and starring Brad Pitt, Seven Years is the story of Harrer’s accidental arrival in Tibet in 1943, and his subsequent friendship with the Dalai Lama and conversion to Buddhism. Johnston, the Oscar-winning co-writer of Prince of Tides, talked with Orville Schell, scholar of Tibetan and Chinese history and dead of Berkeley’s Graduate School of Journalism, about Buddhism, moviemaking, and Hollywood’s current fascination with Tibet. Seven Years was released by Columbia TriStar in October.

Orville Schell: How do you explain the rash of Hollywood films that will soon be out on Tibetan subjects?

Becky Johnston: Well, it’s not hard to understand why Hollywood likes this subject, is it? After all, it’s epic and huge in scope, but kinder and gentler in message than your average story.

Schell: What’s your own personal interest in Tibet?

Johnston: My involvement is accidental. I read the book [Seven Years in Tibet] long ago and was fascinated. I admit I was drawn to the subject because I hoped to find Paradise. I had a fairly romanticized vision of old Tibet as an idealized theocracy based on spiritual principles. I was completely unwilling to see anything negative, like the Chinese argument about a feudal society [laughs]. I think my need, and other people’s need, to idealize Tibet stems from some latent, ancient dream of an earthly Paradise, a place where human goodness, or perfection, has been fully realized. Needless to say, that dream exists only in the mind. And at its core is the desire to re-create oneself, to be made pure, or better, or more complete by touching that place. Tibet was probably the last holdout of that dream.

Schell: Have you become involved in actually studying Tibetan Buddhism or Buddhist spiritual practice as a result of your work on the script?

Johnston: Oh, yeah. I knew there would be no way to attempt writing this script without studying Buddhism. So I looked for someone who could work one-on-one with me for several months. I was lucky to find a brilliant teacher, Tenzin Dorjee, who is a translator for Geshe Gyeltsen at Thubten Dargye Ling. He’s a wonderful, brilliant man who used to be one of the Dalai Lama’s translators in Dharamsala. With me, he was extremely patient, able to make the core concepts of Tibetan Buddhism understandable. For many months, Tenzin and I worked nearly every day, going through a lot of different texts, different teachings, and talking, talking. It quickly became very intense and unsettling. Oftentimes I would find myself railing against everything I was learning. But Tenzin never forced anything or pushed me. He just very gently led me in a direction I had never been before. The experience was earth-shattering. It became much, much more than research.

Schell: And did you end up going to Tibet?

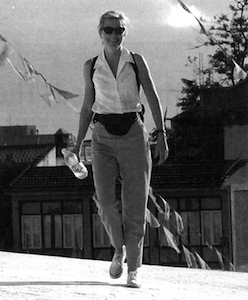

Johnston: Yes, and I went with all my mythological ideas firmly intact. The first trip I spent a month in the Central Valley. Three weeks of it was spent with a Wisdom Publications group led by Stephen Batchelor and Nick Ribush, which was like going on tour with a Tibetan library. Then I spent a week alone in Lhasa. A year later, I went back again by myself for a second trip, to reassess everything I had seen earlier.

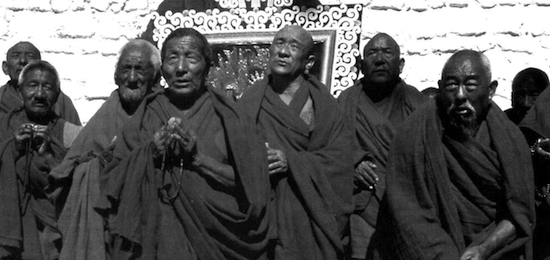

The first experience of Tibet was a little like a bomb going off in my head. I had done a lot of reading about it by then and when finally confronted with the reality, I understood immediately that there was nothing you could read about this place to prepare you for the sheer magnitude of emotion it generates. Firstly, it’s the most singular landscape on earth. Usually when you go somewhere, you say to yourself, “Oh, this reminds me of this place” or “This place looks like someplace else.” You can’t do that in Tibet. It is completely unique, with a scale and scope that reduces you to a mere speck. You can’t believe the beauty of the vistas; the sky is so blue, the colors so intense. And then, there are people who are so profoundly, deeply alive—even under the state of occupation in which they live—that you can’t help but feel humbled. The combination of such a rare landscape and even rarer kind of human being inhabiting it is very, very moving. But even so, being with a group, going through the countryside in a relatively comfortable bus, staying at the Lhasa Holiday Inn, was like seeing Tibet through a fishbowl—a Disneyland kind of tour that in many ways only heightened my preconceived notion of exotica.

Schell: Did you feel that you ever got out of the fishbowl?

Johnston: No, that was one of the great lessons of the trip. If you go to a place wanting it to provide you with a transcendental experience, chances are you won’t have it. Or at least the transcendental moment will catch you unaware. I remember feeling so bad about being a tourist there. I wanted to get inside the soul of Tibet, understand it in a much deeper, more intimate way. This was when I was still traveling with this Wisdom group. So one evening I went to the Jokhnag and did the circumambulation for a long, long time with all the Tibetans, hoping for that hit I’m talking about. And the truth was, as I got swept up in the current of bodies, I became afraid. I realized that as much as I wanted to be a part of them, or their deep devotion, there was a huge, unbridgeable gap. And I would always be the Other to them, as they were the Other to me. It just completely freaked me out. I came back to my hotel room and cried. Because I felt resigned to being shut out, to feeling that I’d never understand these people or open up to that kind of profound experience, as badly as I wanted to. That whole trip was like a dream, it really was. I constantly said to myself, Where am I? This place is so familiar. And then turn around and say—Where am I? This place is so strange. I’m so lost.

Schell: Were things different on your second trip to Tibet?

Johnston: Last year when I went back, I think I had given up the idea that I needed Tibet to transform me, or at least provide me with a grab bag of transcendental experiences. So for this reason it was a clearer trip. I saw it without trying to project myself onto everything. And like a love affair, my feelings were even more powerful when these projections stopped.

Schell: What do you think appeals to visitors so much about it?

Johnston: Its isolation. It is so removed from the world, so remote and separate. For an American, this remoteness fits in with our own personal mythology of the pioneer spirit. Even though in Tibet the individual is not so much esteemed, the landscape forces an almost melancholy sense of your own individuality on you.

Schell: How has an acquaintance with Tibetan Buddhism affected you?

Johnston: My original faith really got shaken by my study of Buddhism. I was a Protestant from Michigan who went to obligatory Sunday school as a kid and never questioned the existence of God. But like all baby boomers, I went through a spiritual crisis and then a period of supermarket spiritual shopping. But I never lost my central, unshakable belief in God during those years. By the time I was deeply into the script forSeven Years, the dharma had pretty much taken over my life, and one of the most personally difficult things I had to deal with was where to fit in God. Where does this belief have a place in Buddhism, which assiduously denies the existence of a creative being, higher power, whatever you want to name it. I would say this was one of the biggest traumas I faced with Tenzin. And I still don’t know quite how to make it work, but I try. What I love so much about Buddhism is that it has helped to take me out of the Western mode of over-rationalizing, of needing a reason for everything. So I try to apply the same open-endedness to this matter of God.

Schell: Has the Dalai Lama figured into all of this?

Johnston: Certainly the Dalai Lama is a huge human magnet for the dharma. People are drawn to Buddhism because of, or through, him. Myself included. And his draw is his total humanity. I mean, someone like me can’t conceive how it’s possible for an enlightened person, a realized being, to be so completely and powerfully present as he is. And you want to get near that presence. In fact, everything I’ve said about my desire to have a transcendental experience in Tibet applies equally to meeting His Holiness. I knew when I left for my first trip to Tibet, I would be going afterward to Dharamsala to interview him. So in my mind, I saw that entire journey as the ascent of a mountain, the summit being my encountering the Dalai Lama in person. And the same need to be transformed by an experience came into play. You know, it’s a combination of vain delusion and naiveté, but I wanted to make some kind of connection. I imagined when I shook the hand of the Dalai Lama, the shakti would rise up my spine from the contact. I hoped there would be some powerful transformative stuff going on. And I was totally unprepared for what actually happened. First of all, I was so incredibly nervous. They took me into a room where he was standing, waiting for me. And I presented a khata to him. He took it and kind of tossed it on the table, as if saying to himself—oh please, not another khata. I was kind of floored. He was so businesslike, so perfunctory, acted as if the interview were a responsibility. Which of course it was, but I was too wrapped up in what I wanted it to be to understand this. Throughout the interview, I was aware that I was comparing my preconceived image of His Holiness to the real person sitting in front of me. One of the most startling incongruities between the image and the reality was seeing how masculine a man he is. I know it sounds crazy, but I kept looking at his hands. He has beautiful, powerful, manly hands. Because His Holiness is celibate, I expected to encounter a eunuch. And I was shocked by how earthy he is, how manly he is. And I was moved, too, because his level of spiritual attainment comes after much renunciation. You realize what he has given up to gain so much. The interview was quite short, only about forty-five minutes. About halfway into it, as he began to talk about his relationship with Heinrich Harrer, he became extremely animated and began to laugh and enjoy himself. And when you see him laugh you say, “This is the Dalai Lama whose image I’ve had fixed in my mind all this time.” It was interesting that I had problems processing all the other facets of his personality.

Schell: Were you disappointed that reality did not compare better with your fantasy of him?

Johnston: It took me several days to recover from the realization that I was just another person on the Dalai Lama’s schedule and that there wasn’t a moment when the earth shook. But as I said, the fact that I couldn’t process other parts of his personality only tells you about my limitations, not his. What I saw was that a person in his position carries a terrible burden, the weight of everyone’s needs as they project them onto him. That’s human nature, but His Holiness gets a megadose of everybody’s human nature since everybody looks to him for something.

Schell: While your film may raise the level of awareness about Tibet’s plight, do you think it might also arouse unfair expectations among viewers about what Tibet is like today and what Tibetan Buddhism can do for them?

Johnston: The appeal of the film—especially with Brad Pitt playing Harrer—is that it is an old-fashioned epic which glimpses a world very few people know or have ever seen. I think people will be affected by the power of the place and by the awareness that another culture so antithetical to our own can exist on the earth. But I think it’s also possible that these films promote the same expectations I’m talking about. It’s possible that they could make millions of people feel that if they could just get this instant fix–get to Tibet or talk to the Dalai Lama—everything will be okay. Seven Years in Tibet may especially promote this because, in the film, Harrer is transformed. The movie shows Tibet having a power over him by planting a sense of love and compassion in him. I would rather be accused of writing a movie that gave people a naive hope of transcendence, than writing a movie that inspired people to stand in the middle of the highway and see if they get hit by a car.

Schell: Are you still deeply involved in Buddhist practice?

Johnston: Not nearly to the extent that I wish I were. A million excuses stand in the way of being a good practitioner.

Schell: Has working on the film been a good experience?

Johnston: I know it sounds corny to say, but on every level, this film has been a blessing. It is the first time that work and life have truly intersected. I find that both have changed. My work feels freer, and my life feels richer.

Schell: Is that the result of Tibetan Buddhism or of the people with whom you have been working?

Johnston: Well, Jean-Jacques is a dream to work with. A writer’s favorite pastime is to complain about directors, and working with him, I’ve been robbed of my pastime. Jean-Jacques is one of those people who is endlessly moved by the mystery of life. He came to this film with such a strong faith in people, including me, and treated me with great respect and generosity. The experience has been a joy.

Schell: How do you explain the allure of Tibet in Hollywood?

Johnston: I think you can’t help being affected by the power of the place and the people. They form the basis of a story that is part fairy tale, part epic, and part tragedy. And certain filmmakers in Hollywood are always looking for the right story to show that the movie industry is not just a dream factory—that it can make serious films that change things, or attempt to, at any rate.

Schell: And the allure of Tibetan Buddhism here in Hollywood?

Johnston: Hollywood is one big altar to artifice and greed. In the midst of this, a way is offered to look at life which strips it down, which may give some kind of meaning. Basically, I think the lavish excesses of Hollywood make everyone here pretty sick. We live in a jaded non-culture where we’ve hit a wall, so we look to another, legitimate culture for new values. I think what’s drawing people to Tibetan Buddhism is a yearning to reduce the self. And a desire to escape the vulgarities of commercialization. What’s interesting when you go to some of the dharma centers in Los Angeles is to see how they are magnets for people who are, in a sense, neither of this world or another. A certain personality seems to come out in this city and be drawn to Buddhism. They are bright people who have not found an emotional outlet in a town where Angelyne billboards are a tourist attraction. They turn to Buddhism hoping to find something real, something deep. Something Other. And in many cases, you sense that they throw themselves completely into this world because they can’t face the one on Sunset Boulevard. But like everything else in Los Angeles people can overdo it, even the dharma. It becomes the answer to everything.

Schell: Are these people misleading themselves?

Johnston: I know for myself, this need to penetrate something strange and inaccessible lies at the heart of my fascination with Tibet. I would guess this is true of many people. But the misconception is that we can really take in, and become part of, another culture made by other people. In that respect I think yes, people are misleading themselves.

Schell: So are the stars in Hollywood who have become enamored of Tibet and Buddhism and all its affectations deluded?

Johnston: I would never presume to say who is deluded and who isn’t. However, I can tell you it looks pretty weird to me to see a big movie star walking around in Chinese satin robes with a fat cigar in his mouth. A lot of people here in Hollywood have egos the size of a whale. You can’t fail to see the irony of putting practice about diminishing the ego through the Hollywood machine, which is really about making the ego more grandiose. The Hollywood machine can turn almost anything into a bloated example of ego running amok.

Schell: Is their Buddhism genuine?

Johnston: Who am I to say? Or to judge? It’s so easy to be cynical here. To the credit of many people in Hollywood, including Steven Seagal and Oliver Stone, their wealth has been used to help others, they have been incredible benefactors to the cause. They’ve sponsored dharma centers and all kinds of events and are certainly far more committed practitioners than I am.

Schell: Do you think the Dalai Lama should do things like come to the premiere of movies like yours when it comes out? Or do you think he should protect a certain aloofness?

Johnston: My guess is that it would probably be best to remain detached and let the movies speak for themselves. As Dalai Lama, he’s done all the work he needs to do to promote his cause. I can’t see how going to a movie premiere would achieve anything more toward that end.

Schell: Might the success of movies like Seven Years in Tibet end up being the Dalai Lama’s undoing by overexposing him and somehow diminishing the respect people have for him?

Johnston: It is true that the heightened profile of the Dalai Lama has helped make Tibet a celebrity cause. Because of these movies, Tibet is poised to become the culture trend of the next year. You can almost feel the groundswell building. But once knowledge about something that has been marginalized gets into the popular culture, it can be dangerous because there is a threat of backlash. Still, the bottom line is that the Dalai Lama is committed to making the world aware of Tibet’s plight, and this movie will undoubtedly heighten that awareness. This was always the hope—to make a good, powerful, entertaining movie that could do something to help, at the same time. If it succeeds, I can’t imagine how people’s respect for His Holiness would be diminished.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.