But we, who cannot fly the world, must seek

To live two separate lives: one, in the world

Which we must ever seem to treat as real;

The other in ourselves, behind a veil

Not to be raised without disturbing both.

—Henry Adams, 1891

In the northeastern quadrant of Washington, DC, there is an old cemetery named Rock Creek. The area surrounding it was once an affluent leafy suburb overlooking the often sweltering city, but the neighborhood that now presses at the cemetery’s iron fence is working-class. Behind that fence, for whatever it may be worth to the tenants, a genteel atmosphere endures. Rock Creek’s hundred rolling acres are covered with traditional burial works from the last three centuries – an impressive landscape of obelisks and angels, twining laurel, and weeping willow.

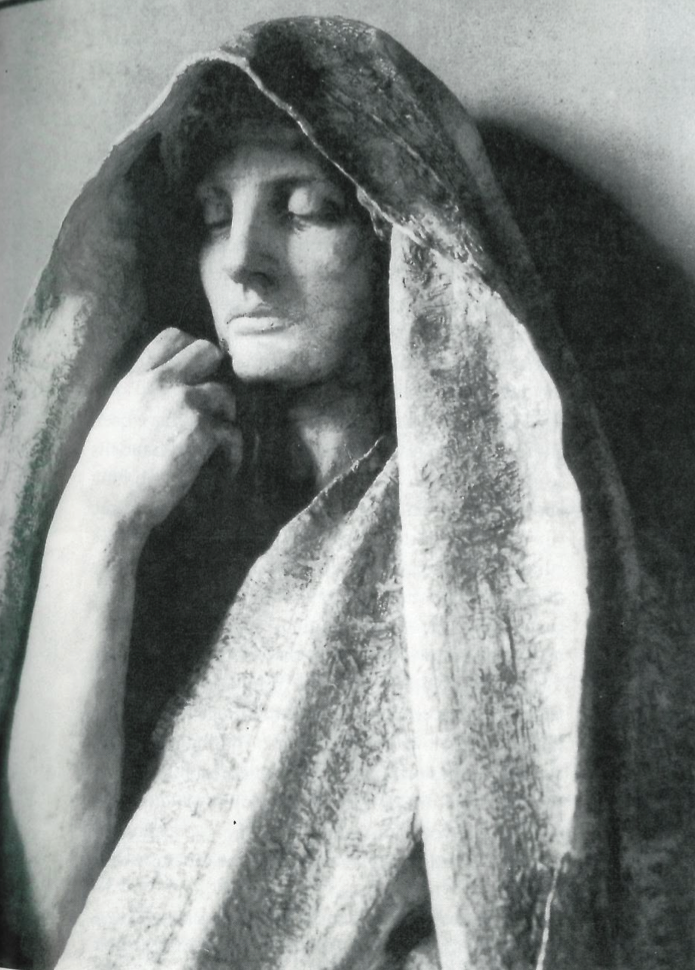

There is also an extraordinary, easily missed exception here. Amid the thousands of reaching monuments, it is turned in on itself and hidden away. To find it you must pass through a miniature copse of yew trees into an enclosure of pink granite. There you will be confronted by the bronze statue of a solitary seated figure of a woman, cloaked head to foot in a heavy cloth. Under a cowling fold is a subdued and inscrutable countenance. The right hand, emerging from the shroud, brushes curiously at the face. There is no name or date or epitaph, no inscription of any kind.

If you have come looking for it, you probably know it marks the graves of Henry and Marian Adams. The art history books will tell you that. The figure was commissioned of the sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens by Henry Adams in memory of his wife and placed here in 1891, five years after her death and twenty-seven before his own. Most of the books will also tell the tragedy behind it: that Marian, nicknamed Clover by her family, took her own life, and that Henry never remarried and never really recovered. Some of the books may mention that the monument was initially regarded by many as a possible affront to religion, and was dubbed “Grief” or “Despair” by the press. But what none of them will say is that the Adams Memorial, made by a non-Buddhist for a non-Buddhist, is perhaps the most significant piece of native Buddhist art in the country.

The story of the monument’s creation centers around a trip to Japan that Henry Adams made with his friend, the painter John La Farge, the summer after his wife’s suicide, and the study Adams made of Buddhism in preparation for that journey. But the place to begin is with the complicated figure of Adams himself.

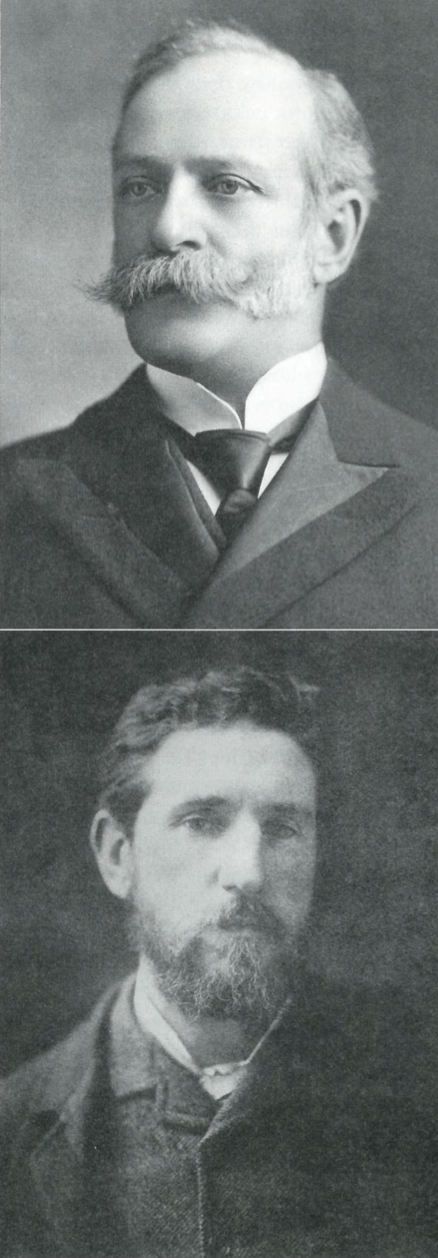

Henry Adams, grandson of the sixth president, John Quincy Adams, was in the course of his long life a diplomat, a beloved Harvard professor, a best-selling novelist, and one of the preeminent historians of his generation. He was also a terribly – one is tempted to say a pathologically – complex personality and, according to himself, a resounding failure. This last assessment serves as the narrative theme of the work for which he is now chiefly remembered: his strange fin de si�cle autobiography, The Education of Henry Adams. The title is ironic. Adams presents his life as a futile and often absurd quest for understanding, which instead brings only mounting bemusement. The real trick of the Education, though, is that along the way Adams manages to indict his entire society on similar charges, thereby transmogrifying an outwardly droll memoir into a prophetic lament on the alienation of the emerging modern age.

But the Education, a masterpiece of cultural commentary, is an autobiography with a gaping hole in its middle. Incredibly, the book makes no mention whatsoever of Clover, the Adamses’ thirteen-year marriage, or her suicide. Into the personal void represented by this vast literary omission, Henry had dropped his heart, often speaking of his life from then on in purgatorial terms – and out of that void of stricken silence rose the monument of Rock Creek.

Although we know from passing references in his letters that Adams studied Buddhist literature and art prior to, and during, his stay in Japan, nowhere does he set down any substantive impressions about Buddhism. Any speculative portrait of what these might have been must encompass two known poles. On the one hand, there is the statue, which Adams referred to in his journals as his Buddha, and to which he attached such importance that he declared once it was finished that he “had no more to worry about in life.”

On the other hand, there is the equally certain fact that Adams never practiced or professed Buddhism in any way.

The evidence does suggest Adams experienced an initial period of receptiveness to Buddhism as a whole that, ironically, was ruined by the visit to Japan itself. The fullest appraisal of Henry’s state of mind before setting sail was left by his niece, Mabel Hooper, who wrote that in the aftermath of Clover’s death, her uncle “plunged into a life of searchings, questionings, and of intense loneliness” in which “Japan and the East beckoned him, and whispered their secrets of abstraction and calm to his suffering soul. It was his first glimpse of peace, since �his life had been cut in halves’ – �infinite and eternal peace – the peace of limitless consciousness unified with limitless will,’ the peace of Nirvana.” Hooper astutely identifies here the essence of Adams’s attraction. It was the inexhaustibly profound notion of nirvana, the blessed cessation of the self and its seemingly insoluble torments, that continued to enthrall Adams when the rest of Buddhism fell away in the choleric heat and grime of preindustrial Japan. Nirvana was the “whispered secret” he pondered beneath the wry persona of the Education for the rest of his life. It was this hidden contemplation that he asked Saint-Gaudens to embody by recasting a Buddha in the Western tradition, in hopes of creating a work, as Adams later described it, that in its “universality and anonymity” represented “the acceptance�of the inevitable.”

Whether Augustus Saint-Gaudens was an inspired choice for this daunting task, or simply a lucky one, we can only guess. Adams knew him through mutual friends before Clover’s death, and the sculptor probably would have been on anyone’s short list of candidates for the commission. Born in Ireland and raised in New York City, Saint-Gaudens had studied and worked in Paris and Rome before returning to the United States to produce several of the most admired public sculptures of his day. His other masterpiece, the Shaw Memorial in Boston, is recognized today as one of the finest bas-reliefs of the modern era.

But it is also hard to believe Adams would have been entirely without reservations about him. Saint-Gaudens admitted from the first that he knew next to nothing about Eastern philosophy or art, and this at a time when interest in the Orient was sweeping through the educated classes of Europe and America. One assumes this would have troubled a man as bookish as Adams, particularly since Saint-Gaudens appeared not to be too concerned with repairing the deficiency. Early on, for example, Adams left some prints of buddhas for Saint-Gaudens to pick up while visiting Washington; the artist left town without them. Writing from New York to request they now be mailed to him, Saint-Gaudens went on to ask if Adams knew of “any book not long that you think might assist me in grasping the situation?” And yet, as we shall soon see, Adams was to exhibit an extraordinary trust in Saint-Gauden’s ability.

Among the many buddhas Adams gave Saint-Gaudens to study, the most influential turned out to be the frequent depiction in Japanese art of the bodhisattva Kuan-yin, or Kwannon, “absorbed in meditations of Nirvana.” Adams had admired a famous statue of Kuan-yin at the imperial mountain retreat of Nikko. In the one extensive meeting between artist and patron, Adams used the sculptor’s young assistant, draped in a rug, to illustrate what became the basic design for the figure.

Saint-Gaudens made a quick sketch in his notebook and, based on their discussion, wrote underneath: “Adams. Buddha. Mental repose. Calm reflection in contrast with the violence or force of nature.” It was when Adams took his leave that he made his somewhat startling show of faith in the artist he had to chosen to bring the East to the West. He told Saint-Gaudens he felt they should not communicate again until the project was finished. If the sculptor felt the need for any further guidance, he could talk to La Farge about it. Otherwise he was on his own.

Saint-Gaudens set to work, then, to produce a very specific design under a patronage of exceptional freedom. He was to make the most of it, taking five years to complete the work, and driving Adams to the verge of regretting his own liberality. Yet it may be to that unusual arrangement that we owe the success of the sculpture. The concept for the figure belonged to Adams. It had been generated by his suffering and taken shape through his scholarship. Adams, however, had been unable to move beyond sufferer and scholar; for reasons of both temperament and circumstance, Buddhism remained a set of abstractions for him. The execution of the idea, however, belonged entirely to Saint-Gaudens, and here we ought to reflect on the fortuitousness of Adams’ choice, for Saint-Gaudens was an artist whose genius was as a practitioner rather than – what is often more highly prized in the Western tradition – a conceptualist. The power of his work comes from an attentive and painstaking patience, a craftsmanship that rises to the level of contemplation. In short, Saint-Gaudens had, in his contentment to express himself by long and “thoughtless” application to conventional forms, a rather Buddhist approach to his art.

While Saint-Gaudens worked, Adams traveled, and fretted over the sculptor’s pace. When the statue was finally unveiled, Adams was again abroad with La Farge, this time in the South Seas. But the work immediately began to cause a stir, and his friends hastily sent their opinions after him. A few seemed to “get” it. Diplomat John Hay wrote Adams that the figure was “full of poetry and suggestion, infinite wisdom, a past without beginning, and a future without end, a repose after limitless experience, a peace to which nothing matters.” But others in Adams’s circle foreshadowed the reservations the public would have. His older brother Charles, who first said it looked like a “mendicant, in a horse blanket,” confided to his diary that the figure must be meant as some sort of justification for the hereditary inevitability of Clover’s suicide. Clarence King said while he thought the work “far above” any other modern sculpture he knew, he saw “not a ray of faith, not a throb of hope” in the shrouded face. And the minister of the cemetery church proclaimed himself horrified by the presence on sanctified ground of an expression of “atheism.”

Upon returning, Adams professed himself very pleased with Saint-Gaudens’ work. Ever the gadfly, he welcomed the clamor over his wife’s memorial with his usual fey equanimity, as simply another sign of the world’s descent into darkness. In the Education he asserted that the idea the figure embodied was not despair, nor should it even be hard to fathom. Its meaning was “the one commonplace about it – the oldest idea known to human thought,” and he claimed any Asian child would have understood it immediately. While he did not deign to say what that idea was, he did add that the inability of the American public to comprehend it was a judgment on them. The cold emptiness they saw in the figure was only their own, a reflection of the despair in themselves that they were either unable or unwilling to acknowledge.

Now Adams was always a great provocateur. But here, pricked by personal anguish, I believe he falls into genuine scorn. Could he really have thought that the meaning of the figure – this Western rendering of the most profound Eastern religious idea – would not have been an enigmatic challenge to his countrymen’s religious conceptions? It seems unlikely, and this failure of his judgment, or of his sincerity, compels us to look again at the figure that began but did not end as his brainchild. For a strong argument can be made that Saint-Gaudens, in his days and nights of artistic labor, had put an apprehensiveness into the design that seems to have begun as pure “mental repose” and “calm reflection.” This appears when one compares his earliest clay models with the figure itself.

There are two obvious differences in the models. First, the figure’s robe hangs much more loose and open about the body, and second, the odd gesture of the hand is not to be found. One clay model has both arms enfolded about the waist; another has a fist raised to the chin in a strong gesture similar to Rodin’s Thinker. Both the looser, lighter robe and the arms held gracefully at the waist are characteristic of the depictions of Kuan-yin, who also typically has a gentle smile. Saint-Gaudens’ final figure, by contrast, is clearly huddled in its bulky shroud; and the fingers caressing the stoical face, the center of individuality, just as clearly suggest an ambivalence that is not to be found in Kuan-yin and that seemingly should be no part of the contemplation of nirvana. Rather than any sort of true repose, a more thoughtful description might be that the figure seems to be trying to settle in to a repose, a contemplation, that up until then has been beyond its understanding. A further hint that Adams missed or ignored the element of pathos or solicitude that Saint-Gaudens, whether consciously or not, had added, is provided by a comparison of the names by which each referred to the nameless work. Adams wrote in a letter that he called it “The Peace of God” – which seems either a glib or a wishful choice for a man who otherwise gave no indication in his life of believing in God at all. Saint-Gaudens’ name does not mention peace or God. He called it simply “The Mystery of the Hereafter.”

Each person of course must interpret the figure for themselves. And Adams is right to point out that ultimately I am responsible for the melancholy I have felt inside the memorial’s enclosing bower. But I also think Saint-Gaudens imbued the Buddha he was asked to make with intimations of a native anxiety of which we need not be ashamed. Buddhist teachers coming to America have sometimes praised a “beginner’s-mind” attitude in the culture. But America is also, more than any society that has ever existed, devoted to the celebration and gratification of the self. It seems to me we ought to be honest about the difficulty and the fear with which we approach the renunciation or the dissolution of our desires, our identities – of all we conceive we are. Henry Adams, who once confessed he “hungered for annihilation,” seems to have found nirvana easy to wish for – and therefore perhaps hard to truly contemplate. Most of the rest of us will have the problem Saint-Gaudens discovered taking shape beneath his hands in the clay: What does it mean to contemplate the end of contemplation and the surrender into pure experience?

Perhaps in years to come the buddhas of Occidental America will take on the more serene expressions of the Eastern ones. But for now the shrouded Bodhisattva of Rock Creek, the Hesitating Buddha, with its downcast eyes, still seems to be peering into the Western soul. ▼

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.