“What do we mean by bodhisattva? Bodhi means enlightenment, the state devoid of all defects and endowed with all good qualities. Sattva refers to someone who has courage and confidence and who strives to attain enlightenment for the sake of all beings. Those who have this spontaneous, sincere wish to attain enlightenment for the ultimate benefit of all beings are called bodhisattvas. Through wisdom, they direct their minds to enlightenment, and through their compassion, they have concern for beings. This wish for perfect enlightenment for the sake of others is what we call bodhichitta, and it is the starting point on the path. By becoming aware of what enlightenment is, one understands not only that there is a goal to accomplish but also that it is possible to do so. Driven by the desire to help beings, one thinks, For their sake, I must attain enlightenment!”

—Tenzin Gyatso, the Fourteenth Dalai Lama

Kosho Uchiyama Roshi

Question: In modern-day terms, what is the significance or meaning of bodhisattva? We can read the old mythological stories about bodhisattvas, but what connection do they have with us today?

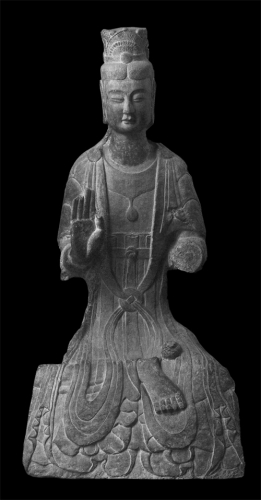

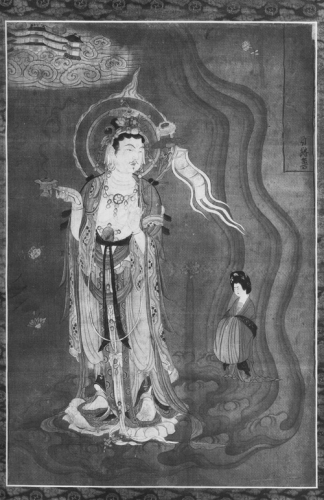

Uchiyama Roshi: A bodhisattva is an ordinary person who takes up a course in his or her life that moves in the direction of buddha. You’re a bodhisattva, I’m a bodhisattva; actually, anyone who directs their attention, their life, to practicing the way of life of a buddha is a bodhisattva. We read about Kannon Bosatsu (Avalokiteshvara Bodhisattva) or Monju Bosatsu (Manjushri Bodhisattva), and these are great bodhisattvas, but we, too, have to have confidence or faith that we are also bodhisattvas.

Most people live by their desires or karma. That’s what the expression gossho no bompu means. Gossho are the obstructions to practicing the Way caused by our evil actions in the past. Bompu simply means ordinary human being—that is, one who lives by karma. Our actions are dictated by our karma: We are born into this world with our desires and may live our lives just by reacting or responding to them. In contrast is gansho no bosatsu, or, a bodhisattva who lives by vow.

The life that flows through each of us and through everything around us is actually all connected. To say that, of course, means that who I really am cannot be separated from all the things that surround me. Or, to put it another way, all sentient beings have their existence and live within my life. So needless to say, that includes even the fate of all mankind—that, too, lies within me. Therefore, just how mankind might truly live out its life becomes what I aim at as my direction. This aiming or living while moving in a certain direction is what is meant by vow. In other words, it is the motivation for living that is different for a bodhisattva. Ordinary people live thinking only about their own personal, narrow circumstances connected with their desires. In contrast to that, a bodhisattva, though undeniably still an ordinary human being like everyone else, lives by vow. Because of that, the significance of his or her life is not the same. For us as bodhisattvas, all aspects of life, including the fate of humanity itself, live within us. It is with this in mind that we work to discover and manifest the most vital and alive posture that we can take in living out our life….

For example, I have people coming here every day to talk with me about their problems. There was one girl a while back who came in and just broke down completely. When I asked her what the problem was, she said she’d gotten pregnant. Apparently she had slept with some guy whom she didn’t even know that well after having gotten quite drunk. I asked her how she felt about marrying him, but she said she didn’t even care for him and couldn’t consider it.

So what should she do? Well, I advised her to have an abortion. She agreed and I referred her to a friend of mine who happens to be a gynecologist. Of course, what I told her to do wasn’t good. It was wrong, or, in Christian terms, sinful. Therefore, if she was going to pay for it in hell, then I would have to go with her. That’s something I had to fully accept the moment she came to me for advice. When someone comes along who’s completely at a loss as to what to do and asks for advice, as a bodhisattva you can’t just say that you don’t know, it’s not your problem. That’s just shirking your responsibility. Not having to take responsibility for what you say or do is the safest way out. But when someone’s all mixed up, what choice have you but to be forceful in replying? What I advised her to do wasn’t a good thing, and if later on she had had to suffer the consequences because of something I’d told her to do, then I would have to be willing to suffer those consequences with her. That’s the kind of reasoning or resolve I felt I had to have to deal with that particular situation.

Related: Buddhist ethics of abortion

Anyway, you should know that it’s not enough for a bodhisattva of the Mahayana to just uphold the precepts. There are times when you have to break them, too. It’s just that when you do, you have to do so with the resolve of also being willing to accept whatever consequences might follow. That’s what issai shujo to tomo ni (“together with all sentient beings”—regardless of what hell one might fall into) really means….

It’s not enough just to know the definition of bodhisattva. What’s much more important is to study the actions of a bodhisattva and then to behave like one yourself.

Regarding the question “What is a bodhisattva?” you could also define a bodhisattva as one who acts as a true adult. That is, most people in the world act like children. The word dainin means “true adult” or “bodhisattva.” Today most people who are called adults are only pseudoadults. Physically, they grow up and become adult, but spiritually too many people never mature to adulthood. They don’t behave as adults in their daily lives. A bodhisattva is one who sees the world through adult eyes and whose actions are the actions of a true adult. That is really what a bodhisattva is.

This passage from Opening the Hand of Thought: Approach to Zen (1993), by Kosho Uchiyama, is reprinted with permission from Penguin Books USA.

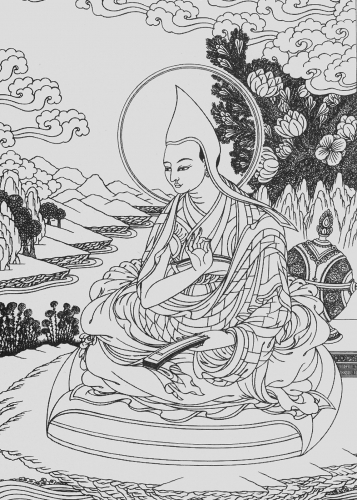

Shantideva

Gladly do I rejoice

In the virtue that relieves the misery

Of all those in unfortunate states

And that places those with suffering in happiness.

I rejoice in that gathering of virtue

That is the cause for [the Arhat’s] Awakening,

I rejoice in the definite freedom of embodied creatures

From the miseries of cyclic existence.

I rejoice in the Awakening of the Buddhas

And also in the spiritual levels of their Children.

And with gladness I rejoice

In the ocean of virtue from developing an Awakening

Mind

That wishes all beings to be happy,

As well as in the deeds that bring them benefit.

With folded hands I beseech

The Buddhas of all directions

To shine the lamp of Dharma

For all bewildered in misery’s gloom.

With folded hands I beseech

The Conquerors who wish to pass away,

To please remain for countless aeons

And not to leave the world in darkness.

Thus by the virtue collected

Through all that I have done,

May the pain of every living creature

Be completely cleared away.

May I be the doctor and the medicine

And may I be the nurse

For all sick beings in the world

Until everyone is healed.

May a rain of food and drink descend

To clear away the pain of thirst and hunger

And during the aeon of famine

May I myself change into food and drink.

May I become an inexhaustible treasure

For those who are poor and destitute;

May I turn into all things they could need

And may these be placed close beside them.

Without any sense of loss

I shall give up my body and enjoyments

As well as all my virtues of the three times

For the sake of benefiting all.

By giving up all, sorrow is transcended

And my mind will realize the sorrowless state.

It is best that I [now] give everything to all beings

In the same way as I shall [at death].

Having given this body up

For the pleasure of all living beings,

By killing, abusing, and beating it

May they always do as they please.

Although they may play with my body

And make it a source of jest and blame,

Because I have given it up to them

What is the use of holding it dear?

Therefore I shall let them do anything to it

That does not cause them any harm,

And when anyone encounters me

May it never be meaningless for him.

If in those who encounter me

A faithful or an angry thought arises,

May that eternally become the source

For fulfilling all their wishes.

May all who say bad things to me

Or cause me any other harm,

And those who mock and insult me

Have the fortune to fully awaken.

May I be a protector for those without one,

A guide for all travelers on the way;

May I be a bridge, a boat, and a ship

For all who wish to cross [the water].

May I be an island for those who seek one

And a lamp for those desiring light,

May I be a bed for all who wish to rest

And a slave for all who want a slave.

May I be a wishing jewel, a magic vase,

Powerful mantras and great medicine,

May I become a wish-fulfilling tree

And a cow of plenty for the world.

Just like space

And the great elements such as earth,

May I always support the life

Of all the boundless creatures.

And until they pass away from pain

May I also be the source of life

For all the realms of varied beings

That reach unto the ends of space.

Just as the previous Sugatas

Gave birth to an Awakening Mind,

And just as they successively dwelt

In the Bodhisattva practices;

Likewise for the sake of all that lives

Do I give birth to an Awakening Mind,

And likewise shall I too

Successively follow the practices.

In order to further increase it from now on,

Those with discernment who have lucidly seized

An Awakening Mind in this way,

Should highly praise it in the following manner:

Today my life has [borne] fruit;

[Having] well obtained this human existence,

I’ve been born in the family of Buddha

And now am one of Buddha’s Children.

Thus whatever actions I do from now on

Must be in accord with the family.

Never shall I disgrace or pollute

This noble and unsullied race.

Just like a blindman

Discovering a jewel in a heap of rubbish,

Likewise by some coincidence

An Awakening Mind has been born within me.

It is the supreme ambrosia

That overcomes the sovereignty of death,

It is the inexhaustible treasure

That eliminates all poverty in the world.

It is the supreme medicine

That quells the world’s disease.

It is the tree that shelters all beings

Wandering and tired on the path of conditioned existence.

It is the universal bridge

That leads to freedom from unhappy states of birth,

It is the dawning moon of the mind

That dispels the torment of disturbing conceptions.

It is the great sun that finally removes

The misty ignorance of the world,

It is the quintessential butter

From the churning of the milk of Dharma.

For all those guests traveling on the path of conditioned existence

Who wish to experience the bounties of happiness,

This will satisfy them with joy

And actually place them in supreme bliss.

Today in the presence of all the Protectors

I invite the world to be guests

At [a festival of] temporary and ultimate delight.

May gods, anti-gods and all be joyful.

This passage from A Guide to the Bodhisattva’s Way of Life, by Shantideva, is reprinted with permission from the Library of Tibetan Works and Archives, Dharamsala.

Sharon Salzberg

“I had a loving mind, a mind wishing for others’ welfare. Bodhisattvas are like that.”—Shakyamuni Buddha

There is a common misconception that there is no such thing as the Bodhisattva Vow in the Theravadin tradition. However, there is such a path. In the classical Theravadin tradition, the Bodhisattva Vow is undertaken by those who aspire to full buddhahood, rather than to the liberation of an arhant. While an arhant is said to be entirely free of grasping, aversion, and delusion, and thus enlightened, his or her scope of manifestation is more limited than that of a fully awakened buddha. We are, as an example, all still enjoying the legacy of the Buddha’s enlightenment of 2,500 years ago. It is vast compassion which motivates one to endeavor to full buddhahood, and the aeons of fulfilling the paramis, or perfections, that are necessary. A Theravadin practitioner who aspires to serve that powerfully takes the Bodhisattva Vow. While most Theravadin practitioners aspire to the condition of an arhant, there are said to be some following the bodhisattva path today.

The paramis are the contributory conditions to enlightenment, or the facets of an enlightened mind. According to the Buddhist teaching there is an accumulated force of purity in the mind that is the ground out of which freedom arises. The bodhisattva will spend lifetime after lifetime creating this ground by cultivating generosity, morality, renunciation, energy, truthfulness, patience, resoluteness, loving-kindness, equanimity, and wisdom. It is only in the particular lifetime during which the bodhisattva becomes a buddha that wisdom itself is brought to perfection. The role of the paramis is often depicted in the legend surrounding the enlightenment of the Buddha.

On the very eve of his enlightenment, the Buddha, then still a bodhisattva, sat under the bodhi tree and was attacked by Mara. Mara is a mythic figure in the Buddhist cosmology who is the “killer of virtue” and the “killer of life.” Mara, recognizing that his kingdom of delusion was greatly jeopardized by the Bodhisattva’s aspiration to full awakening, came with many different challenges in an attempt to get the Bodhisattva to give up his resolve. He challenged him through lust, anger, and fear. He showered him with hailstorms, mud storms, and other travails. No matter what happened, the Bodhisattva sat serenely, unmoved by the challenge and unswayed in his determination.

The final challenge of Mara in effect was one of self-doubt. He said to the Bodhisattva, “By what right are you even sitting there with that goal? What makes you think you have the right even to aspire to full enlightenment, to complete awakening?” In response to that challenge, the Bodhisattva reached over his knee and touched the earth. He called upon the earth itself to bear witness to all of the lifetimes in which he had practiced generosity, patience, morality, and other perfections. Lifetime after lifetime he had built a wave of moral force that had given him the right to that aspiration.

Any practitioner of the Buddha’s teaching is called upon to practice the perfections, to make heroic effort, and to be able to rest confidently on a base of moral force. The distinction between those determining to realize full buddhahood and those committed to arhanthood is actually one of degree. The Buddha’s teaching, whatever one’s goal, is never removed from a sense of humanity. He described the motivation principle of his own life as a dedication to the welfare and the happiness of all beings, and also encouraged the same dedication in others: we all can see our lives as vehicles to bring happiness, to bring peace, to bring benefit to all living things, without exception.

Sharon Salzberg has been practicing in the Theravada tradition since 1971 and is one of the founders of the Insight Meditation Society in Barre, Massachusetts.

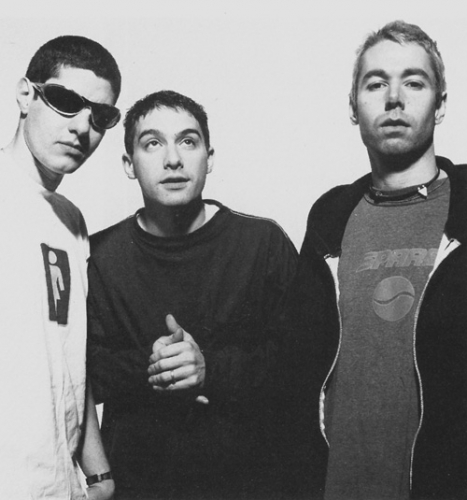

Adam Yauch of The Beastie Boys

The following lyrics are by Adam Yauch, a band member of the rap group The Beastie Boys. This song appears in their newest album, Ill Communication.

Bodhisattva Vow

As I develop the awakening mind

I praise the Buddhas as they shine

I bow before you as I travel my path

To join your ranks, I make my full the task

For the sake of all beings I seek

The enlightened mind that I know I’ll reap

Respect to Shantideva and all the others

Who brought down the dharma for sisters and brothers

I give thanks for the world as a place to learn

And for the human body that I’m glad to have earned

And my deepest thanks to all sentient beings

For without them there would be no place to learn what I’m seeing

There’s nothing here that’s not been said before

But I put it down now so that I’ll be sure

To solidify my own views

And I’ll be glad if it helps anyone else out too

If others disrespect me or give me flack

I’ll stop and think before I react

Knowing that they’re going through insecure stages

I’ll take the opportunity to exercise patience

I’ll see it as a chance to help the other person

Nip it in the bud before it can worsen

A chance for me to be strong and sure

As I think of the Buddhas who have come before

As I praise and respect the good they’ve done

Knowing only love can conquer hate in every situation

We need other people in order to create

The circumstances for the learning that we’re here to generate

Situations that bring up our deepest fears

So we can work to release them until they’re cleared

Therefore it only makes sense

To thank our enemies despite their intent

The bodhisattva path is one of power and strength

A strength from within to go the length

Seeing others are as important as myself

I strive for a happiness of mental wealth

With the interconnectedness that we share as one

Every action that we take affects everyone

So in deciding for what a situation calls

There is a path for the good for all

I try to make my every action for that highest good

With the altruistic wish to achieve buddhahood

So I pledge here before everyone who’s listening

To try to make my every action for the good of all beings

For the rest of my lifetime and even beyond

I vow to do my best to do no harm

And in times of doubt I can think on the dharma

And the enlightened ones who’ve graduated samsara.

Related: A Guide to (Sort of) Buddhist Rock Music

Pat Enkyo O’Hara

Sitting on my zafu, the Bodhisattva Vow seems natural, almost automatic. The heart opens, and then the day follows with The New York Times: a picture of people cheering around Baruch Goldstein’s grave in Hebron; two Japanese boys killed in an L.A. mall; news that the Mayor proposes to eliminate the Department of AIDS Services, which has enabled several of my friends to die in dignity. My anger rises like a wind. Words float to the surface of my consciousness: racism, homophobia, hatred, greed. How can I open my heart, how can I even want to save all sentient beings?

That is the crux of it: how to see my interdependence with those I instinctively want to shun, to shut out of my world?

Politically, I came of age with so many others in the sixties. We marched, protested, and learned not to blindly accept the way things were—to be arrested, to “put our bodies on the line,” to, in today’s words, “act up.” Many of us also learned to hate, to view the “other”—cop, soldier, politician—not as a brother or sister conditioned by karma, not as self, but as an enemy.

And yet, what such separation breeds is readily apparent: more rage, more violence, more suffering. The answer doesn’t lie there. But seeing the other as self is not easy, which is why I sit. Ultimately, it’s what makes working with the Bodhisattva Vow possible.

So, as I read my newspaper and catch myself solidifying that sense of separation, I take in a breath, soften and loosen myself a little. I ask myself where my commonality with Baruch Goldstein and his followers, with the Mayor, with the L.A. killers lies? Another breath. What must it have been like to grow up as a Goldstein in Brooklyn? As a gang member in L.A.? What kind of terrible conditions did they face? What kind of suffering did they endure? Can I imagine the pain, smell the fear?

I think of how some babies come screaming into the world, seem bad-tempered from the start, and how hard it is to hold a baby like that. Can I feel myself as the screaming baby, uncomfortable, dissatisfied? As the mother, frightened, irritated?

Can I catch my own irritation and fear and not run from it? Can I tolerate my own helplessness? Can I observe myself as I rush to defend my point of view with the same bullying tactics I condemn in “the other”? To the extent than I can see the soldier, the fundamentalist, the terrorist in me—view my own “stuff’ and not separate from it—to that extent can I connect to “the other.” It’s the same stuff.

So with each breath, I confirm that the skinheads are my sons, the fundamentalists, me. And each time I do this, there’s more space inside of me and I can allow more in. Their suffering, my suffering. In breath, out breath.

Pat Enkyo O’Hara practices Zen in the Soto tradition and is Associate Professor of Interactive Telecommunications at Tisch School of the Arts, New York University.

Rev. Tetsuo Unno

We begin in Pure Land Buddhism with the understanding that it is not the sentient being who strives toward becoming a bodhisattva, a being whose essence is enlightenment but who refrains from entering nirvana in order to save others; rather, it is the bodhisattva who strives to save the sentient being and transform it into bodhisattva.

Sentient beings, in other words, are viewed as powerless and incapable of bringing about their own salvation and enlightenment or bodhisattvahood. They are seen as utterly lacking the moral and spiritual capacity to transform themselves into bodhisattvas.

The unchanging and unchangeable nature of a sentient being is like that of a monkey who trained himself to become human. In this parable a monkey, to the bemused amazement of many, succeeded to the point that he was asked to perform in kabuki plays. For his human-like performances he often drew shouts of approval. One day, however, someone threw peanuts onto the stage, whereupon the monkey suddenly reverted to his simian nature and scampered after them and shoved them into his mouth. The apparent transformation had merely been a superficial one.

The bodhisattva known as Dharmakara perceived this incapacity of sentient beings to transform and save themselves, and moved by compassion, vowed to create those conditions that will lead to their salvation. To bring this vow to fruition, he undergoes aeons of spiritual practices, of which the essence is egolessness.

Ultimately, the Bodhisattva Dharmakara attains Buddhahood and becomes the Buddha of Infinite Compassion and Wisdom, or Amida Buddha. Although a Buddha, he vows not to retreat into transcendent Buddhahood until the very last sentient being is saved and attains Buddhahood.

The sentient being’s only task then is to serve as the recipient of Amida Buddha’s salvific efforts. It does so by the acts of absolutely entrusting itself to Amida’s vow of unconditional salvation. The act of entrusting oneself and of being saved are, in reality, one and the same. The following incident, which took place a number of years ago, illustrates the nature of this oneness.

A sailor aboard a freighter crossing the Pacific Ocean fell overboard. The crew first noticed that he was missing eighteen hours later. The captain, however, ordered the ship to go back in search of the lost sailor. Miraculously, they found the sailor floating in the water and nearly asleep. He later explained that there was nothing at all he could do to save himself, so he simply entrusted himself to the buoyant powers of the ocean, which held him up and so, finally, saved him. The oneness of entrusting and salvation finds its parallel in the philosophical notion that negation and affirmation are one; or, in mythology, in stories that show the identity of death and birth.

Moreover, Saint Shinran of the Shin Sect of Pure Land Buddhism teaches that beings who entrust themselves to Amida Buddha are made the equal of Bodhisattva Maitreya, who in the next stage is destined to become a Buddha. The implication here is that those who have entrusted themselves to Amida Buddha are made the equal of a bodhisattva; it is taught, however, that full buddhahood or the consummation of bodhisattva hood is attained only after shedding one’s physical body, i.e., dying. Metaphorically, this means that, for example, when caught in a two-hour traffic jam, beings who have entrusted themselves to Amida Buddha may, by virtue of that entrusting, retain bodhisattva-like inward calm and freedom from such blind passions as anger. This does not, however, mean that outwardly or physically those same beings are endowed with the power to fly freely over the cars in front. Physically, they are as limited as the other drivers trapped in that traffic jam.

Having been endowed with this great gift of salvation and, by implication, bodhisattvahood—not despite but becausesentient beings are, if left to their own devices, utterly beyond attaining either—sentient beings are filled with an inexpressible sense of absolute gratitude. With this gratitude—which one philosopher described as being “the greatest of virtues because it is the parent of all others”—as their ethical foundation, sentient beings live out their lives, bodhisattvically striving to help others to free themselves from ignorance and suffering, all the while attributing both the cause and effect of those actions to Amida Buddha.

Reverend Tetsuo Unno is a minister and follower of the Jodoshinshu sect of Pure Land Buddhism.

Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche

Taking the Bodhisattva Vow implies that instead of holding onto our individual territory and defending it tooth and nail we become open to the world that we are living in. It means we are willing to take on greater responsibility, immense responsibility. In fact it means taking a big chance. But taking such a chance is not false heroism or personal eccentricity. It is a chance that has been taken in the past by millions of bodhisattvas, enlightened ones, and great teachers. So a tradition of responsibility and openness has been handed down from generation to generation; and now we too are participating in the sanity and dignity of this tradition….

The sanity of this tradition is very powerful. What we are doing in taking the Bodhisattva Vow is magnificent and glorious. But joining this tradition also makes tremendous demands on us. We no longer are intent on creating comfort for ourselves; we work with others. This implies working with our other as well as the other other. Our other is our projections and our sense of privacy and longing to make things comfortable for ourselves. The other other is the phenomenal world outside, which is filled with screaming kids, dirty dishes, confused spiritual practitioners, and assorted sentient beings.

So taking the Bodhisattva Vow is a real commitment based on the realization of the suffering and confusion of oneself and others. The only way to break the chain reaction of confusion and pain and to work our way outward into the awakened state of mind is to take responsibility ourselves. If we do not deal with this situation of confusion, if we do not do something about it ourselves, nothing will ever happen. We cannot count on others to do it for us. It is our responsibility, and we have the tremendous power to change the course of the world’s karma. So in taking the Bodhisattva Vow, we are acknowledging that we are not going to be instigators of further chaos and misery in the world, but we are going to be liberators, bodhisattvas, inspired to work on ourselves as well as with other people.

There is tremendous inspiration in having decided to work with others. We no longer try to build up our own grandiosity. We simply try to become human beings who are genuinely able to help others; that is, we develop precisely that quality of selflessness which is generally lacking in our world. Following the example of Gautama Buddha, who gave up his kingdom to dedicate his time to working with sentient beings, we are finally becoming useful to society.

We each might have discovered some little truth (such as the truth about poetry or the truth about photography or the truth about amoebas) which can be of help to others. But we tend to use such a truth simply to build up our own credentials. Working with our little truths, little by little, is a cowardly approach. In contrast, the work of a bodhisattva is without credentials. We could be beaten, kicked, or just unappreciated, but we remain kind and willing to work with others. It is a totally noncredit situation. It is truly genuine and very powerful.

Taking this Mahayana approach of benevolence means giving up privacy and developing a sense of greater vision. Rather than focusing on our own little projects, we expand our vision immensely to embrace working with the rest of the world, the rest of the galaxies, the rest of the universes.

Putting such a broad vision into practice requires that we relate to situations very clearly and perfectly. In order to drop our self-centeredness, which both limits our view and clouds our actions, it is necessary for us to develop a sense of compassion. Traditionally this is done by first developing compassion toward oneself, then toward someone very close to us, and finally toward all sentient beings, including our enemies. Ultimately we regard all sentient beings with as much emotional involvement as if they were our own mothers. We may not require such a traditional approach at this point, but we can develop some sense of ongoing openness and gentleness. The point is that somebody has to make the first move.

Usually we are in a stalemate with our world: “Is he going to say he is sorry to me first, or am I going to apologize to him first?” But in becoming a bodhisattva we break that barrier: we do not wait for the other person to make the first move; we have decided to do it ourselves. Millions of people in the world are suffering because of their lack of generosity, discipline, patience, exertion, meditation, and transcendental knowledge. The point of making the first move by taking the Bodhisattva Vow is not to convert people to our particular view, necessarily; the idea is that we should contribute something to the world simply by our own way of relating, by our own gentleness.

In taking the Bodhisattva Vow, we acknowledge that the world around us is workable. From the bodhisattva’s point of view it is not a hard-core, incorrigible world. It can be worked with within the inspiration of the buddha-dharma, following the example of Lord Buddha and the great bodhisattvas. We can join their campaign to work with sentient beings properly, fully, and thoroughly—without grasping, without confusion, and without aggression. Such a campaign is a natural development of the practice of meditation because meditation brings a growing sense of egolessness.

By taking the Bodhisattva Vow, we open ourselves to many demands. If we are asked for help, we should not refuse; if we are invited to be someone’s guest, we should not refuse; if we are invited to be a parent, we should not refuse. In other words, we have to have some kind of interest in taking care of people, some appreciation of the phenomenal world and its occupants. It is not an easy matter. It requires that we not be completely tired and put off by people’s heavy-handed neurosis, ego-dirt, ego-puke, or ego-diarrhea; instead we are appreciative and willing to clean up for them. It is a sense of softness whereby we allow situations to take place in spite of little inconveniences; we allow situations to bother us, to overcrowd us.

Our talents are not rejected but are utilized as part of the learning process, part of the practice. A bodhisattva may teach the dharma in the form of intellectual understanding, artistic understanding, or even business understanding. So in committing ourselves to the bodhisattva path, we are resuming our talents in an enlightened way, not being threatened or confused by them.

It is necessary at this point to take a leap in terms of trusting ourselves. We can actually correct any aggression or lack of compassion—anything anti-bodhisattva like—as it happens; we can recognize our own neurosis and work with it rather than trying to cover it up or throw it out. In this way one’s neurotic thought pattern, or “trip,” slowly dissolves. Whenever we work with our neurosis in such a direct way, it becomes compassionate action.

The usual human instinct is to feed ourselves first and only make friends with others if they can feed us. This could be called “ape instinct.” But in the case of the bodhisattva vow, we are talking about a kind of superhuman instinct which is much deeper and more full than that. Inspired by this instinct, we are willing to feel empty and deprived and confused. But something comes out of our willingness to feel that way, which is that we can help somebody else at the same time. So there is room for our confusion and chaos and egocenteredness: they become stepping-stones. Even the irritations that occur in the practice of the bodhisattva path become a way of confirming our commitment.

By taking the Bodhisattva Vow, we actually present ourselves as the property of sentient beings: depending on the situation, we are willing to be a highway, a boat, a floor, or a house. We allow other sentient beings to use us in whatever way they choose. As the earth sustains the atmosphere and outer space accommodates the stars, galaxies, and all the rest, we are willing to carry the burdens of the world. We are inspired by the physical example of the universe. We offer ourselves as wind, fire, earth, and water—all the elements.

But it is necessary and very important to avoid idiot compassion. If one handles fire wrongly, he gets burned; if one rides a horse badly, he gets thrown. There is a sense of earthy reality. Working with the world requires some kind of practical intelligence. We cannot just be “love-and-light” bodhisattvas. If we do not work intelligently with sentient beings, quite possibly our help will become addictive rather than beneficial. People will become addicted to our help in the same way they become addicted to sleeping pills. By trying to get more and more help they will become weaker and weaker. So for the benefit of sentient beings, we need to open ourselves with an attitude of fearlessness. Because of people’s natural tendency toward indulgence, sometimes it is best for us to be direct and cutting. The bodhisattva’s approach is to help others to help themselves. It is analogous to the elements: earth, water, air, and fire always reject us when we try to use them in a manner that is beyond what is suitable, but at the same time, they offer themselves generously to be worked with and used properly.

One of the obstacles to bodhisattva discipline is an absence of humor; we could take the whole thing too seriously. Approaching the benevolence of a bodhisattva in a militant fashion doesn’t quite work. Beginners are often overly concerned with their own practice and their own development, approaching Mahayana in a very Hinayana style. But that serious militancy is quite different from the lightheartedness and joy of the bodhisattva path. In the beginning you may have to fake being open and joyous. But you should at least attempt to be open, cheerful, and at the same time, brave. This requires that you continuously take some sort of leap. You may leap like a flea, a grasshopper, a frog, or finally, like a bird, but some sort of leap is always taking place on the bodhisattva path.

There is a tremendous sense of celebration and joy in finally being able to join the family of the buddhas. At last we have decided to claim our inheritance, which is enlightenment. From the perspective of doubt, whatever enlightened quality exists in us may seem small-scale. But from the perspective of actuality, a fully developed enlightened being exists in us already. Enlightenment is no longer a myth: it does exist, it is workable, and we are associated with it thoroughly and fully. So we have no doubts as to whether we are on the path or not. It is obvious that we have made a commitment and that we are going to develop this ambitious project of becoming a buddha.

This is from Heart of the Buddha by Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche (1940-87), reprinted with permission from Shambhala Publications.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.