Burton Watson, an occasional professor at Columbia University and a regular resident of Japan, is a prolific and masterful translator of Chinese and Japanese. His earliest works appeared in the sixties and were translations of Chinese classics, ranging from the Records of the Grand Historian of China (Columbia University Press, 1961) to The Complete Works of Chuang Tzu(Columbia University Press: 1968). But in addition to translations of histories, prose, and Taoist texts, there are at least half a dozen publications of Watson’s translations of Chinese and Japanese poetry, all of which remain in print.

Burton Watson, an occasional professor at Columbia University and a regular resident of Japan, is a prolific and masterful translator of Chinese and Japanese. His earliest works appeared in the sixties and were translations of Chinese classics, ranging from the Records of the Grand Historian of China (Columbia University Press, 1961) to The Complete Works of Chuang Tzu(Columbia University Press: 1968). But in addition to translations of histories, prose, and Taoist texts, there are at least half a dozen publications of Watson’s translations of Chinese and Japanese poetry, all of which remain in print.

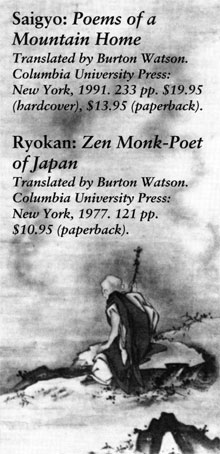

Saigyo: Poems of a Mountain Home is Watson’s most recent collection of poetry in translation. Saigyo (1118-1190 C.E.) was a Buddhist poet-priest who ranks as one of the most influential court poets of Japan. Although relatively little is known of his life, he was apparently born into a well-connected warrior family and practiced martial arts as a young man, but was not unfamiliar with Japanese court life. Saigyo quit secular life when he was twenty-two, but for some time the lure of the social and political life of the city continued to strain his monastic commitments.

Watson has translated two hundred of Saigyo’s poems while providing a romanized version of the originaI Japanese. The poems are presented in a traditional “seasonal” arrangement, along with chapters on Love, Miscellaneous, and Poems from the Kikigaki shu (a short text of Saigyo poems discovered in 1929). One of the love poems reads:

Now I understand—

when you said “Remember!”

and swore to do the same,

already you had it

in mind to forget

And another poem from the same chapter is no less immediate:

“I know

how you must feel!”

And with those words

she grows more hateful

than if she’d never spoken at all

Readers who would like to see more of Saigyo’s poems should also keep in mind William LaFleur’s Mirror for the Moon (New Directions, 1978), which contains 173 poems in translation.

Although published in 1977, Ryokan: Zen Monk-Poet of Japan bears mentioning because it is another of Burton Watson’s excellent translations of the works of a Buddhist monk-poet. According to many commentators, Ryokan (1758-1831 C.E.) had an understanding of Buddhist practice that could easily have qualified him to head a temple, but instead he chose to live in solitude in mountain huts and a renovated storehouse. Ryokan composed in both Chinese and Japanese; Watson’s text includes forty-three poems from the Chinese, eighty-three Japanese poems, and an essay on begging for food.

The following poem is from a group of poems written for children who died in a smallpox epidemic:

When spring comes,

from every tree tip

the flowers will unfold,

but those fallen leaves

of autumn, the children,

will never come again.

Selected Writings of Nichiren

Translated by Burton Watson and others;

edited and introduced by Philip Yampolsky.

Columbia University Press: New York, 1990.

502 pp. $47.50 (hardcover).

Nichiren (1222-1282 C.E.) lived during Japan’s Kamakura period (1185-1333 C.E.) when new Buddhist movements were flourishing. Shinran (1173-1262 C.E.), founded the True Pure Land or Jodo Shin sect, Eisai (1141-1215 C.E.) is generally regarded as founder of the Rinzai sect of Zen, and Dogen (1200-1253 C.E.) initiated the Soto Zen School in Japan.

Nichiren lived during a period of rebellion, conspiracies, threatened invasion, famine, and social turmoil, all of which he blamed on the government’s refusal to accept “true” Buddhism as it is presented in the Lotus Sutra. His teaching was distinguished by a style that intended to facilitate conversion by provoking and combating adherents of what he considered to be false schools of Buddhism. Zen, Nembutsu, and Pure Land practices were all equally derided.

The Selected Writings of Nichiren includes “The Five Major Works of Nichiren,” his best-known doctrinal efforts, an autobiographical sketch, and miscellaneous letters. The translations were selected from a larger multi-volume work prepared by Burton Watson and others titled The Major Writings of Nichiren Daishonin. The larger work was begun in the late seventies by the Nichiren Shoshu International Center, a group allied with the Nichiren Shoshu sect.

The Legend and Cult of Upagupta: Sanskrit Buddhism in North India and Southeast Asia

By John S. Strong.

Princeton University Press: Princeton, 1992.

390 pp. $45.00 (hardcover).

Buddhist tradition maintains that Upagupta was a master of both meditation and vinaya (discipline), and recognizes him as one of the patriarchs responsible for the early transmission of the Buddha’s teaching in India. Although Upagupta is curiously absent from the Pali canon, Sanskrit sources provide different accounts, suggesting that he was a spiritual adviser to King Asoka, leader of the Sarvastivadin sect in early Buddhism, and a forest monk whose mountain monastery was a center of pilgrimage until the seventh century C.E.

Professor Strong (whose Legend of King Asoka is equally recommended) does not attempt to reconstruct an historical Upagupta or to demythologize the legends and narratives connected with him. Instead, The Legend and Cult of Upagupta attempts to arrive at a more complete picture of the legend, cult, and significance of Upagupta by combining textual surveys with the study of oral, ritual, and iconographic materials. Strong’s study provides fresh insights, both historical and exegetical, about the nature of Sanskrit Hinayana Buddhism and contemporary Buddhism in Southeast Asia, where Upagupta’s cult continues to the present.

The Essential Confucius: The Heart of Confucius’ Teachings in Authentic I Ching Order

Translated by Thomas Cleary.

HarperSanFrancisco: San Francisco, 1992.

179 pp. $18.00 (hardcover).

The Essential Tao: An Initiation into the Heart of Taoism Through the Authentic Tao Te Ching and the Inner Teachings of Chuang- Tzu

Translated by Thomas Cleary.

HarperSanFrancisco: San Francisco, 1991.

168pp. $18.00 (hardcover).

Thomas Cleary is so prolific that one can think of him not so much as a translator but as a cottage industry. Nevertheless, his translations are always innovative and make the texts extraordinarily relevant to our time. In the Essential Confucius, the Analects are arranged systematically, with passages grouped topically around each of the sixty-four hexagrams of the I Ching, a traditional arrangement adopted by the “editors” of the I Ching. This explanation may sound confusing, but Cleary’s arrangement is not. A random example is hexagon number forty-three from the I Ching, or Book of Changes:

Good people distribute blessings to reach those below them, while avoiding presumption of virtue.

The facing page provides the selections from the Analects that offer a kind of commentary on the lines: “Confucius said, ‘If people are in high positions but are not magnanimous, if they perform courtesies without respect, or if they attend funerals without sadness, how can I see them?”’; and “Confucius said, ‘Virtue is never isolated; it always has neighbors.'” This example illustrates how the juxtaposition of Confucius and the I Ching serves to promote the understanding of both texts and their respective ideas.

Cleary’s Essential Tao is also a case of combining two sources to illuminate one of the classic traditions of China. In this case, however, both texts are within the Taoist tradition: the Tao Te Ching itself and Chuang-Tzu’s (c. 368-286 B.C.E.) “Inner Teachings” or “Inner Chapters.” The translations are very direct, honest, accessible, and on occasion, uncannily pertinent. Chapter thirty from the Tao Te Ching begins:

Those who assist human leaders with the Way do not coerce the world with weapons, for these things are apt to backfire. Brambles grow where an army has been; there are always bad years after a war…

—Stuart Smithers

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.