Anthony Poon wasn’t looking for a teacher or a spiritual practice in 2008 when he received a call from an old friend. The Tibetan Buddhist community at the Bodhi Path retreat center in Natural Bridge, Virginia, had some building projects in mind, and she wondered if that would interest him.

Friendship aside, Poon was not an obvious choice. An architect with degrees from the University of California, Berkeley, and the Harvard Graduate School of Design, he has over three hundred projects to his name and a slew of prestigious awards, including, in 2018, the American Institute of Architects’ highest accolade, the National Design Award for Best in Housing Design. Poon Design, based in Los Angeles, is known for elegant, modernist designs for luxury residences, upscale restaurants, and cutting-edge commercial, educational, and cultural facilities. Though Poon’s portfolio contains several churches and a chapel for Air Force retirees, at the time of his friend’s phone call he had never been inside a Buddhist center.

But Poon is no stranger to designing for the spirit, whether the building is a bona fide house of worship or simply “something to facilitate enriched lives,” as he wrote in Sticks & Stones/Steel & Glass: One Architect’s Journey. He worked closely with a visionary Catholic nun to create a center for homeless women and children in downtown LA, pioneered a genre-busting affordable housing project in the California desert, and designed a Holocaust and Human Rights library in Maine as well as remembrance memorials for Martin Luther King Jr., victims of 9/11 and AIDS, and former slaves. But what may have impressed the Buddhists even more than his résumé is his deeply held design ethic and philosophy of life. “Architecture creates a place to rest. To learn. To think. To grow. To connect,” he wrote. “It nurtures us, helps us to be better people.”

For the Bodhi Path retreat center, Poon turned out to be an ideal choice. And for Poon, a moment of curiosity turned into a life-changing exploration.

Located in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley, on 40 acres of lush rural land surrounded by a 400-acre undeveloped buffer zone, the retreat center at Natural Bridge was founded by the late Mipham Chokyi Lodro Rinpoche, the 14th Shamarpa and Red Hat Lama, second only to the Karmapa in the hierarchy of the Karma Kagyu school. In 1996, Shamar Rinpoche (as he is also known) established Natural Bridge as the North American retreat center for Bodhi Path, his innovative, nonsectarian, modern approach to buddhadharma, oriented toward making the traditional teachings and practices relevant to life today and available to all.

For Poon, who also trained as a concert pianist (and still plays for pleasure), architecture is about listening: “Our job as architects is to really get to know what the client is about—what their beliefs are and their stories.”With the Buddhists, that meant total immersion in life at the retreat center, joining the sangha for teachings, meditation, and retreats, social events and meals. “Lots of my time was spent getting to know the community of Bodhi Path. I wasn’t just designing architecture for them; I was being present with them.”

When Poon arrived, existing structures on the land included a meditation hall, the Enlightenment Stupa with a path for kora—circumambulation— and a scattering of cabins for individual retreats. For his first commission—a meditation cabin—he designed a simple wooden house evoking the vernacular style of rural Virginia. “In keeping with the Buddha’s teachings,” he later wrote, “I approached the design by the Path of Moderation.” Informally, he dubbed it “Middle-Way architecture.”

For Poon, a moment of curiosity turned into a life-changing exploration.

Poon graduated to more than meditation cabins when he was chosen to build out the Shamarpa’s vision and the two began a close collaboration. Their meetings—“intimate though diverse in venue,” as Poon describes them in Sticks & Stones—moved between the Virginia retreat center, Poon’s LA office, and his Hollywood Hills home (over dinner with his two young daughters). For Poon, some of their most memorable times were spent sketching building designs together. “The 14th Shamarpa could draw,” he says. “We sketched some doodles, ideas for the future of the retreat center.”

Sustainability was always part of the plan. “Architects need to be more conscious about how we respect our environment,” emphasizes Poon, who is LEED-accredited by the U.S. Green Building Council.“We need to be advocates for the future and to be able to sustain our environment as it is. It’s not just about using solar panels and recycled material. It’s how you think of the world as a community and working together to have a successful future.” At Bodhi Path, “the first part of sustainability was how we placed the buildings, keeping the footprint small so they don’t take over the landscape, block the views, or require chopping down too many trees.”

Related: The Work That Reconnects

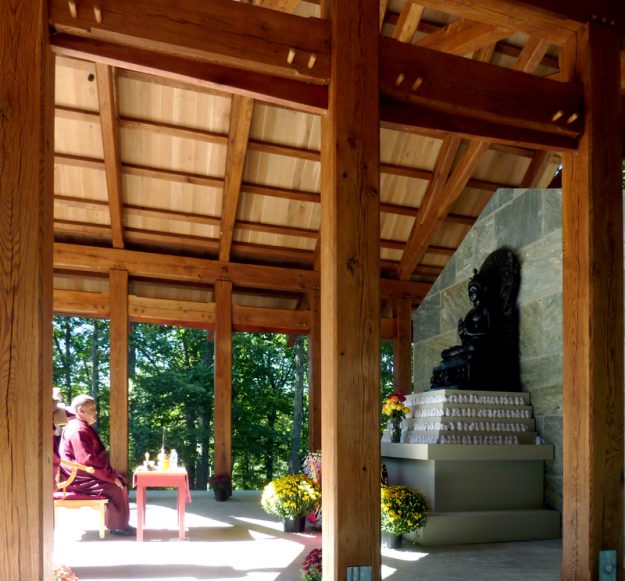

Poon’s next project was the Buddha Pavilion, an open-air temple housing a large bronze Buddha. There, sustainability meant using local materials and volunteer labor. “We wanted to involve all the members of the community,” he says. Guided by skilled artisans, sangha members hand-built the structure using heavy-timber construction, an ancient, labor-intensive method of wood framing that involves no modern tools, relying on traditional joinery techniques like mortise and tenon. It took several dozen people working together to carve each of the ninety or so timber beams. Poon also designed a small support building 50 feet from the temple for restrooms, pumps, and other equipment.

Related: Little Tibet Welcomes a Little Bauhaus

Shamar Rinpoche dedicated the Buddha Pavilion in 2013. A year later, as construction was nearing completion, he died unexpectedly at age 61. Poon was chosen to design a reliquary building. One of just three structures in the world entrusted with the Shamarpa’s relics and the only one in America, the reliquary is down the hill from the Buddha Pavilion. The 20-by-30-foot glass box, surmounted by a copper roof—a traditional element of Tibetan architecture—is theatrically lit to showcase the 6-foot gold-leafed stupa containing the relics. Unlike Poon’s more rustic designs for the center, the pavilion called for state-of-the-art infrastructure, including climate-control measures like double glazing and a 5-foot overhang on the roof, to ensure preservation of the Shamarpa’s relics in perpetuity.

Sangha members built the structure using an ancient, labor-intensive method that involves no modern tools.

Poon’s most recent design for Bodhi Path is a two-story multipurpose dining commons/community building with large windows framing the spectacular mountain views. Poon calls the airy space “the family room of the campus.” Construction is slated to begin this year or next, once fundraising has reached its goal.

Poon visits the retreat center several times a year to discuss plans for future development and participate in meditation retreats. His initial curiosity about Buddhism evolved into interest in the teachings and practices through his bond with Shamar Rinpoche, then segued into commitment when Poon formally took refuge with Karma Trinlay Rinpoche. One sangha member sums up the progression: “Anthony started coming regularly to our programs first as an architect, then as a student, then as a Buddhist.” With characteristic modesty, Poon insists, “I consider myself a beginner and just starting the path.”

In his designs for Bodhi Path, Poon has very consciously avoided the kind of grandstanding that big-name architects often indulge in. “For these projects it’s about listening to the community, not me going there and presenting ambitious visions I whipped up in a vacuum.” He continually thinks how best to reflect the Shamarpa’s vision: contemporary, future-oriented, yet authentically Buddhist.“We want to do buildings that are beautiful,” Poon says, “but we also understand that they are a backdrop for something much more important, which is the practice of Buddhism.”

Photograph courtesy Poon Design

Photograph courtesy Poon Design

Photograph courtesy Mark Ballogg

Photograph courtesy Mark Ballogg

Photograph courtesy Mark Ballogg

Photograph courtesy Mark Ballogg

Photograph courtesy Mark Ballogg

Photograph courtesy Mark Ballogg

Photograph courtesy Mark Ballogg

Photograph courtesy Mark Ballogg

Photograph courtesy Mark Ballogg

Photograph courtesy Mark Ballogg

Photograph courtesy Poon Design

Photograph courtesy Poon Design

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.