I’m in my car, on the highway. I turn off the news reports and the baseball game I’ve been listening to and switch to a Beethoven violin sonata that’s loaded in the CD player. Listening to the music, my mind gradually starts to release, like a hand that had been grasping something tightly and is beginning to let go. Another mind appears, a mind completely engaged with the pattern the music weaves. A moment before, I’d been frozen into the shape of a self in a world. Now, the music has thawed me out.

The world and the self really do appear to us as frozen. Our personal problems, our self-definitions, what we hear from those around us—all these convincing and compelling experiences invite us to clutch at concepts, positions, worries. We naturally build vast structures of ice to hold in place the world and the self, chilly and confined. But the experience of art can shake us free of all that. Art can save us from freezing.

Spiritual practice can, too. It can provide us with a much larger view of our lives, a warming, melting view. At least this is the theory. But anyone who’s done spiritual practice for a while can tell you that it doesn’t always work that way. In fact, spiritual practice too often hits us with an arctic blast, icing us over, if we are not careful, into more grotesque shapes than the ones we were in before we began practice. Why? Because we tend toward ice: We crave a secure sense of self, a truth we can depend on, a world we can tame and understand. We want to be frozen, even as we long desperately to thaw. Religion is problematic because we are problematic.

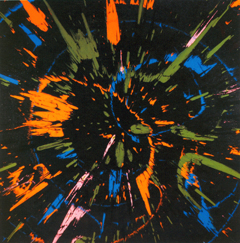

But that snatch of music, that poem, that picture—these can make a big difference. The imagination situates us in a reality wider, deeper, and more mysterious than we can directly sense or rationally know. Imagination can see into and through the apparent world to something luminous and significant. Without imagination there is only plodding on in a two-dimensional world, merely surviving, getting through the day. Without imagination we feel only the world’s dead weight, like an albatross around our necks, hanging there without rhythm, without quickness, without a beating heart.

Zen has probably saved me from myself; poetry has probably saved me from Zen.

But imagination is tricky and wild. It does not play by the rules; it cannot be controlled or second-guessed. No surprise, then, that imagination is depicted as a goddess, a muse, who comes when she wants to and leaves without notice. From the point of view of the rationally organized world, imagination is dangerous, for it holds that world in supreme irony, as a mere backdrop for its colorful activity. No wonder Plato wanted to exclude the poets from his Republic. And no wonder religion almost always mistrusts and fears the imagination, which is forever evoking energies—sexual and creative energies—religion would just as soon forget: they are just so messy and hard to control, and they are not usually polite.

Related: My Brief Career Composing Spanish Music

Imagination draws its energy from a confrontation with desire. It feeds off desire, transmuting and magnifying reality through desire’s power. Fantasy does the opposite; it avoids desire by fleeing into a crude sort of wish-fulfillment that seems much safer. Fantasy might be teddy bears, lollipops, sexual delights, or superhero adventures; it also might be voices in one’s head urging acts of outrage and mayhem. Or it might be the confused world of separation and fear we routinely live in, a threatening yet seductive world that promises us the happiness we seek when our fantasies finally become real. Imagination confronts desire directly, in all its discomfort and intensity, deepening the world right where we are. Fantasy and reality are opposing forces, but imagination and reality are not in opposition: imagination goes toward reality, shapes and evokes it.

So although spiritual practice seems necessarily to be, and historically has been, at odds with imagination, the truth is that spiritual practice requires imagination. If we really want to go beyond the surface of things to the deeply hidden, actual experience of being alive (as spiritual practice encourages us to do), we need imagination as an ally. The senses, reason, even our moral and emotional faculties are not enough.

Small children have an easygoing and natural sense of imagination. For them there’s no serious difference between the world of matter and the world of dreams; they crisscross and mix all the time. But children have to learn to freeze the world, to get it to hold still, so they can figure out how to be persons in it in some organized way.

Spiritual practice ought to be childish. It ought to help us recapture something that gets lost in the process of growing up. It ought to foster a sense of play, a sense of magic, a sense of humor, so as to avoid the occupational hazard of freezing. Probably it’s too hard to cultivate these qualities within the normative forms of any spiritual tradition, so working with the imagination through art is good for spiritual practitioners. And the reverse holds as well: spiritual practice is good for artists. As a Zen priest I have been saved from freezing by my practice as a poet; as a poet I have been driven deeper by my practice of Zen. Zen has probably saved me from myself; poetry has probably saved me from Zen.

Working with the imagination through art requires discipline. This is developed through an encounter with the materials. At first, you approach art out of passionate personal need to express your inexpressible feelings. But once you wade in, you find that the medium—the words or paint or sounds—is extremely resistant to your self-expression. Things don’t just fall into place. You have to grapple with the materials, reshaping yourself to suit them. It turns out that making art is not so much self-expression as a dialogue between what we think we want to express and the materials that seem to have their own demands. Engaging in this dialogue moves you to a degree of attentiveness and concentration beyond the private and the personal. It also moves you to encounter art’s own traditions, constructed on terms much different from those of spiritual traditions.

Art practice gives us a path into the rich and unique content of our own lives. I don’t need art to know what I think and feel. But without art, what I think and feel quickly becomes circular, self-centered, and limited. Making or appreciating art gives me a way to start with what I think and feel and then to plunge deeply enough into it that it becomes not only what I think and feel but also what anyone thinks and feels and, even beyond this, what isn’t thought or felt at all. When I write or read poems I am met, through my own thought and feeling, by what’s outside my thought and feeling. In this sense, art practice promotes a profound empathy, a widening of my sphere of awareness.

Art practice can help us overcome the weakness we all have for religious doctrine and dogma. Art provides a way to discover truth, but not the sort of truth that is handed to us already vetted. Instead, we must find it ourselves anew. This is a much more difficult and intimidating proposition.

We who are engaged in spiritual practice should never forget how painful and destructive such practice may become when our enthusiasm for the truth of whatever tradition we are pursuing becomes exclusive. Not only does narrowness of view cut us off from others who practice and believe differently than we do, it also cuts us off from ourselves, as we slash away at our thoughts and feelings in an effort to fit them to the shape of the doctrines we hold dear.

Art practice can move the inner life of the spiritual practitioner out from under the dictates of tradition and challenge it with a demand for freshness. This has been my experience. My lifelong involvement with poetry has kept me sane within a fairly narrow and rigorous life of religious practice.

We need art as a form of recreation, re-creation of ourselves and our world, a freshening of what goes on day by day in our ordinary living. Viktor Shlovsky, the Russian formalist critic, arguing for attention to formal detail in art, said, “To make a stone stony—this is why there is art.” Art defamiliarizes the familiar, and thereby makes it new. Artists know this, but not only artists. We all sense that in looking at the world outside our own personal interests and habits we can feel something of the divine, of the whole. We can, therefore, approach our daily tasks with this heightened sense of things, taking care of our homes, our relationships, our communities, and ourselves with attentiveness and love—that is, as if we were artists grappling with our materials.

Being human is a big job. So much to do! Taking care of body, mind, soul, taking care of ourselves and each other emotionally and physically, repairing the world, earning a living—it’s endless. There’s no use worrying about finishing the job or even doing it all that well. But to brightly begin, and then, having begun, to continue: that’s the great thing.

THE NIGHT IS RED

currents and portends

so many tears in the bogs

the rabbis continue to contend

and Syliva—where is Sylvia?—

who is Sylvia?

reward perhaps for the horses

around here, they look Korean

as only Chinese horses can

and cleaning up round the corners

myself the famous poet no one’s heard of

except to say there was a rumor

he was a poet, had crossed the line

in bridge when he came to that page

a monk tossed like a ball

in the streaming bumpy current

left with th eproblem of the practice

of how not to have faith in anything

sufficient regard

of course so as long as Jack agrees

and as long as the night is red

♦

From Slowly But Dearly, © 2004 by Norman Fischer. Published by Chax Press in June 2004. Reprinted with the permission of publisher.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.