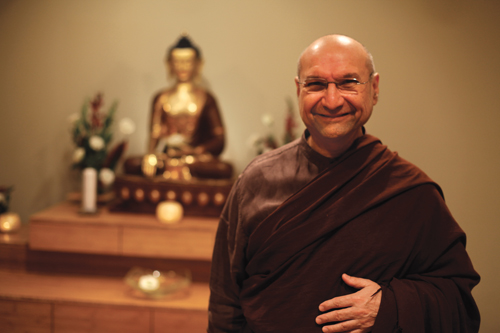

Segyu Rinpoche is not your typical Tibetan monk. Born to Brazilian parents in Rio de Janeiro, he trained as an electrical engineer before becoming a master healer in Brazil’s rich healing tradition. Later drawn to the Tibetan Buddhist tradition, he studied for 25 years under the guidance of Gelug master Kyabje Lati Rinpoche (1922–2010), former abbot of Tibet’s Gaden Shartse Monastery. In 1983, shortly after arriving in the United States, he was recognized by the head of the Gelug school as holder of the Tibetan Buddhist lineage known as the Segyu.

As a Westerner, Segyu Rinpoche is unequivocal and outspoken when it comes to issues often sidestepped by the Gelug hierarchy. Women, he insists, qualify for full ordination. Same-sex relationships? They in no way contradict the Buddha’s teachings; in fact, they are consistent with them.

As a teacher, Segyu Rinpoche is highly innovative, modifying or dismissing those rituals, practices, and beliefs he considers irrelevant, and indeed obstructive, when it comes to transmitting the teachings to Westerners. Following the advice of the Dalai Lama, he has concluded that many of the traditional Tibetan practices and ways of teaching must be adapted to the cultural sensibilities of Westerners if Westerners themselves will one day successfully serve as lineage holders. At the same time, he remains rooted in his tradition.

Segyu Rinpoche has a relaxed relationship with his students—one that is more easily defined by respect than by rigid hierarchy. Together with his students he founded the Juniper school, whose apt motto is “Buddhist training for modern life.”

Tricycle caught up with Segyu Rinpoche at his home in Redwood City, California.

—James Shaheen

You received Buddhist teachings from traditional Tibetan monks, who recognized you as a tulku, a reincarnate lama. How did you come to this tradition? Ever since I was a child in Brazil, I had been interested in the meaning of spiritual life, and I was often told I had a special gift in this area. Although I trained in the tradition of Brazilian healing, at first I didn’t pay full attention to my inner life. I graduated from college as an engineer, married and had a daughter, and worked in the computer industry for a while. But eventually it became clear that ignoring my spiritual life was a mistake.

One day a friend showed me a statue of Je Tsongkhapa, the founder of the Gelug school of Tibetan Buddhism, and told me that I had a very strong connection with him. I recognized the statue from visions I’d had as a young boy. That was the beginning of my interest in the Buddhist path. The more I entered into the Buddhist tradition, the easier it was for me. It made intuitive sense. Eventually I was recognized as a reincarnate master and my teacher, Kyabje Lati Rinpoche—one of the great contemporary Tibetan Buddhist masters—pushed me to become a teacher myself.

What led you to set off in your own direction? I felt the teachings were not being fully transmitted to Westerners. There were many barriers. I saw that the lamas had a difficult time understanding the psychological profile of Westerners. It was difficult for Westerners to absorb the teachings as they were transmitted and to maintain them. For example, Westerners like to question and explore, and we adapt to new information quickly. Tibetan monastic education, in contrast, perpetuates a tradition without questioning it. It rarely changes. Also, while Westerners respect monastic life, it is not significant in our culture the way it has been in others. So to transmit these teachings in the West, we have to overcome these and other barriers.

It sounds like you realized this early on, but it was a while before you acted on these insights. I was continuing to shape my skills, particularly in healing, which is really about cultivating and applying energy for the benefit of others. And it took time to understand how to bridge the gap. I was lucky to have an unbelievable master, Kyabje Lati Rinpoche, the former abbot of Gaden Shartse monastery, under whom I studied from 1984 until his passing in 2010. But the challenge was a big one—-building a bridge between a thousand-year-old Tibetan monastic tradition and a modern world that is so different. How could Westerners become fully capable of holding that lineage and the energy associated with it? How could Westerners themselves learn to transmit the teachings?

What answers did you arrive at? I felt that Tibetans, after a half century outside Tibet, were teaching the tantras to Westerners in an overly intellectual way. They were not transmitting the energy itself, as they did in the monasteries. Every day you can see new gurus and tantric masters showing up, giving empowerments, and moving on. Yet where are the Westerners holding this lineage energy? Why can’t a Westerner give an initiation?

Where did these questions put you in relation to the tradition? I am within the tradition. I respect and honor it, and the work I’d done earlier in Brazil was parallel to it. But I did not blindly follow it. I was able to distinguish between the Tibetan culture and the essence of the teachings. I continued doing my healing work while teaching the classical Tibetan tradition. Eventually I had a fair number of exceptional students, but many felt there were barriers to comprehending the Tibetan tradition.

About ten years ago, some of these students came to me with questions like, “Why do we have to follow forms that are foreign to us? Is this a condition for inner growth, or would it be better to find ways more culturally appropriate?” What could I say to this? I agreed with the problem. So we began a process of challenging assumptions, discussing the teachings, their relevance to Westerners, and the cultural barriers. One thing we all agreed on was that accessibility was an issue.

Later on we saw that His Holiness the Dalai Lama had written in his book The Meaning of Life from a Buddhist Perspective, “It is important to adopt the essence of Buddha’s teaching, recognizing that Buddhism as it is practiced by Tibetans is influenced by Tibetan culture and thus it would be a mistake to try to practice a Tibetanized form of Buddhism.” And that’s exactly it. Solving that challenge is what we were doing.

How did you work together with your students when you took on the task to render the traditional teachings in contemporary idiom? Here’s an analogy for how we worked together: Imagine a star far away. In order to focus on it, I cannot look at you and you cannot look at me. We both need to look at the star. That is how we worked. We envisioned that we were on a journey to a distant place, and we all had to focus on it and do our part. Through eight years of study, debate, and practice, we were able to do that—eight years, full-time, Hillary Brook Levy, Lawrence Levy, Pam Moriarty, Christina Juskiewicz, and me. We started in 2003, and the website juniperpath.org went up in 2009. That was full time—Monday through Thursday, from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m., meetings, doing retreats together, and the headaches of 24/7 thinking and talking, weekends, and all that. From that emerged Juniper, which is a school that provides, as we say, “Buddhist training for modern life.” Our main task was to make sure we did not throw out the baby with the bathwater—to keep the essence and potency intact.

How did the group decide what was baby and what was bathwater? Great question. The short answer is: insight and experience. This is something we discussed and debated intensely, and we continue to do so even today. From my side, I relied on the insight and experience I’d had of the teachings, because I have to honor those experiences. Ideas I thought were essential were sometimes not, and sometimes the team discovered that ideas it wanted to throw out were essential. Little by little we polished our model and kept going. The more we debated and practiced, the more clarity we developed.

Can you give me an example of something you felt was or was not essential? Take the Tibetan practice of prostration. It’s a way to show respect for the teacher and the tradition, and it is a practice said to purify the mind. But although that may be true for a culture accustomed to prostration, it may not be true for a culture where that custom does not exist. In such a culture it could even be off-putting to one’s mind. Just the same, you do need a way of displaying respect, because if you’re too casual you might lose the possibility of transformation. We can apply a modern methodology to gain the same result. The question is, how do we find a balance? How do we modify that method in culturally appropriate ways and still skillfully enhance the mind?

How did you answer those questions? We dropped the prostrations but not the idea of respect. Respect is a powerful tool. The problem is when we confuse respect for the teacher with the notion that this teacher is a supreme and infallible being. Simply adopting a ritual can conceal the teachings and present forms that fail to serve us as they should. At Juniper we call this the problem of “reification.” It means the process of suspending critical thinking and holding up something as more than it actually is, like seeing a teacher as a king or a god.

How do you handle this? The trick is to remove the inessential aspects—the negative cultural artifacts—yet maintain the potency of the method. If you just follow someone blindly, like you sometimes see in the teacher/student relationship, it is limiting. So how does the teacher gain enough respect so that when he or she says something that triggers you emotionally and holds out the possibility of transformation, you do not simply turn away or blame the teacher?

So the cultural forms themselves can become a distraction? Absolutely. In both ways, the old culture and the new. Both have to be understood.

How would a student express the respect you refer to, then? If you really understand the path you’re walking, your commitment to walking it will naturally engender respect. Like an athlete respects the coach in order to bring about his or her potential.

How would a student express the respect you refer to, then? If you really understand the path you’re walking, your commitment to walking it will naturally engender respect. Like an athlete respects the coach in order to bring about his or her potential.

When you mention energy and power, how do you understand it? If it is embodied by the teacher, doesn’t that create the sort of relationship that is one not of respect but of great inequality? Those words—energy and power—worry me. I don’t think they translate well. Let’s take the classical understanding. In the classical tradition, they refer to a “potent” master. What they refer to in this sense is a “very well realized” teacher who, by their realization, can help you to achieve that same realization.

You use “energy” and “power” and “realization” in close context. Can you speak to that? I try to avoid the word “realized” because it could take us into the realm we want to avoid—sanctification, reification, putting a person up on a pedestal. I translate it as energy, which is really what is being transmitted. That energy is used to bring about transformation, and that’s what I talk about when I say energy.

In fact, each one of us has levels of the energy I’m talking about. Some have high energy but little control over it. Others have high energy that is blocked. And some have weaker energy that needs to be developed. Power is the capacity to enhance that energy, to apply that energy properly. I was empowered because my teacher himself was realized and passed that energy on to me. Now I hold that seed and can pass it to others, and so on. “Energy” is the best word I can come up with, but it’s not perfect. I also try to avoid getting trapped in the new age groove.

You discuss lineage often. What do you mean by it, especially since some may see you as having broken your lineage? Up until he died two years ago, I had an unbelievably close relationship with my teacher—for over 25 years. He supported everything I am doing. Our relationship was based on mutual devotion, love, and understanding. Lineage is a particular tradition that is passed along from teacher to student. We receive transmissions— seeds—and put them into practice, and that will produce fruits and new seeds. Those new seeds will be able to propagate to new students, and so on. This process isn’t particular to a culture. What we have done is extend this lineage in a way that is suited to a Western understanding of this tradition and an ability to use it. So it is not at all broken. Enjoying this accessibility in our culture also comes with a responsibility, however. If we want this tradition to be ours, and to pass it on to future generations, we have to have the will to maintain it. This is Juniper’s most important task, finding and encouraging individuals in our culture who will take pride and joy in this effort.

We rely heavily on the bedrock Buddhist principle of critical thinking—testing the teachings as you would gold. What we found was that little of that is happening at many dharma centers. We’ve taken contemporary knowledge, physics, neuroscience, and so forth, and applied them to karma, reincarnation, and so forth. We ask, where does this new knowledge require that we look anew at old knowledge? What survives critical analysis? This has been exactly the crux of the discussions we’ve had and continue to have. It is a process of deconstruction. What could be more consistent with Buddhist teachings?

Where do you come down on reincarnation, then? Next question, please! [Laughs.] We don’t follow the classic presentation of reincarnation. In the classical model, the mind is defined as “luminous” and “knowing” and “immaterial.” We know that the immaterial cannot affect the material; that cannot not be the case. Many Tibetans still believe in the immaterial, but we must avoid making statements for which we have no evidence.

There are younger tulkus and scholars who have a different, more modern view. Juniper has a modern view. We say that you are the cumulative result of all that has come before. Everything is a continuation of what came before. So why worry about the rest? Pay attention to now. We have a great capacity for growth, and we must put our attention on it now, at this moment! This way, we do not have to make reincarnation the focus.

As for what happens when we die, we cannot say for sure. My belief is that something happens, but I don’t follow the classic interpretations for what that is. We do a lot of work with the dying, and in that work we apply the transition of the mind practices of our lineage. We have developed a beautiful, accessible version of it. All I can say from my experience is that it helps. It helps calm people as they prepare to pass, and it helps the transition that occurs at death, however one may choose to describe it.

The Dalai Lama once said to us at a conference at Stanford University that whenever science undermines a traditionally held belief, we must let that belief go. Take traditional Tibetan cosmology—it’s clearly outdated. Yet two days after I sat on the stage with the other monks and heard His Holiness say that, I went to visit a venerated master to present our work at Juniper. We mentioned what the Dalai Lama had said. The master responded, “He’s saying that for Westerners. That knowledge of our world is hidden. When you really become a buddha, you will be able to see Mount Meru at the center of a flat earth.

How did you answer? I said, “Thank you,” but my thought was that this master is strongly conditioned in one belief, one that is obsolete. It’s dogma, nothing else.

Many people believe all sorts of things. Some dismiss evolution, for instance, or the notion that human activity affects the climate. People who have such convictions—fundamentalists, say—tend to exert great influence, often to our detriment. Why is the counternarrative so weak? Because we permit too much blind action based on fear, without proper rationale. The dogma and fundamentalist views in our culture are still very strong and deep. We have to push back harder.

Can’t it also be that we’re living in question? Is that mistaken for a lack of conviction? To question is unbelievably powerful. But if you question all the time and you remain in doubt, going first this way and then that, conviction is absent. If you develop a line of inquiry and learn from your experience, conviction grows. Then you put that conviction into practice but remain open to new information and experience. You set a steady course and remain willing to grow and learn. That is powerful.

So you advocate engagement and taking a stand? Yes. We try to follow the thoughts of the Buddha: if we want to change the quality of our experience, we need to go inside and develop our minds and apply what we’ve learned. Think of how creative we are. It’s wonderful. With deepening conviction we can change for the better. I think Buddhism is a cutting-edge methodology for advancing human civilization. It’s not based on old, inaccessible scriptures. It depends on the methodology of inquiry. That brings about real conviction. Drop dogma so you can see to your own growth.

Have your own convictions about the classical teachings triggered a negative response? They haven’t. We are not at war with classical tradition. We should be careful not to demean it. We should honor it without backing out of the more modern view. We can do that without attacking anyone. In time, I believe, we’ll gain a strong voice.

We are not interested in dogma, which is the trap so many fall into when they adhere to long-held beliefs. To be dogmatic is to hold to a view no matter what, no matter how things change. That’s not the sort of stand we take.

At Juniper we definitely take positions, political and otherwise. For instance, on our website we take a position in favor of same-sex marriage and know that we are arguing in a way that is entirely consistent with Buddhist teachings.

The Dalai Lama has said that Buddhists should not be involved in same-sex relationships, and yet you’ve argued otherwise. Is this a case of not following blindly? I think definitely that’s the point. I think the Dalai Lama might say that to protect Tibetan monastic culture, but I cannot make a judgment about his position.

Let’s look at it differently. In our quest for freedom, enlightenment, or whatever we want to call it, we have to let go of our conventions. Favoring a particular gender, sexual preference, or way of life cannot be the definitive way to freedom. These are merely aspects of how we appear in the world right now. They are no more limiting than having blue eyes or small hands. I think the Dalai Lama understands this but cannot be so open as we’d like sometimes, as he must adhere to a traditional Tibetan view of things.

This is why I wear brown robes and not red. I could not take part in an interview like this if I were wearing the other robes. A different voice—that’s what wearing brown means for the Juniper school.

Have you received criticism from traditional teachers in the Gelug school? No. As I said before, I don’t attack them or offend them. I praise them as holders of a great tradition. I went through the tradition, and I know how to behave within it. I have a strong relationship with my fellow Gelugs.

You seem easygoing about this. So many people have had such nasty breaks with the tradition. Put it this way: I had no crisis. It doesn’t change my capacity to be a monk because I believe differently. A lot of people reacted strongly to the cultural pressures of the tradition, but my status as a rinpoche, I suppose, made it easier for me. I believe in the work of Juniper, and I’m very comfortable and confident in my brown robes.

Do you ever wear red robes any more? It’s been a gradual transition. In 2010, when I went to India to pay respects to my teacher, I wore red robes. And when I go to special initiations, and so on, I’ve worn red. In the near future red will fade into brown. This way, I am a bridge between the old and the new.

How would you describe your teaching style? Most of the time I like to lead from behind the scenes. We can pay a price for the traditional guru model. In that model, one does nothing without consulting the teacher. Some become so narrow in their view and so dependent that they become dysfunctional. There’s no critical thinking. This is not healthy. I don’t like it because it blocks their creativity, independence, and growth, and so on.

When people ask me what to do and then resist, I ask, “What do you want?” If you don’t have the capacity to modify your way of being right now, there’s no point to doing anything else. You continue being the way you are. I am patient, though. Maybe the opportunity will arise at a later time. That’s okay. I have been successful with that model, and without demanding or expecting that anyone do what I say.

Curiosity, engagement, and awareness bring growth. On the other hand, resistance, or thinking you know, only perpetuates your way of being, your patterns. It’s up to you.

I think we are very fortunate we can do what we are doing at Juniper, and now our goal is to open to more people to engage in this process.

And ritual? Pujas? Initiations? You dismissed them once, but now you’ve reintroduced them to some extent, although much modified. People can get lost in life, and ritual can provide them with a framework. What do I do? I think ritual is an important methodology. Ritual loses power when it becomes a method of reification, pure devotion without knowing what you’re doing, with blind belief and fear. Then you lose capacity for transformation. We are doing with ritual what we are doing with the expression of the teachings: making it more accessible and understandable.

Do you consider Juniper an experiment? Absolutely not. Juniper is not an experiment. It’s real. It’s a spiritual lineage. It is Buddhist training for modern life.

Photographs by Mirissa Neff

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.