In 1976, I read a great essay in the second edition of the fine but short-lived publication Loka: A Journal from Naropa Institute. I’ve remembered the essay for more than forty years, and though my memory of many specifics had faded, my recollection of the experience of reading it remained vivid. It opened up the world in a surprising and compelling way. I was changed by it. The essay was called “The Coconut Monk,” and it was written by John Steinbeck IV. John was, as you might guess, the son of the iconic American author; he was also an immensely gifted writer in his own right. The essay resurfaced for me recently when I came across the book The Other Side of Eden: Life with John Steinbeck. When John died suddenly in 1991, he was roughly midway through writing his autobiography, and his wife, Nancy, took up the task of finishing it, though it would be more accurate to say that she both filled it out and completed it with her own singular perspective. The resulting collaborative memoir was published in 2001, and I wish I had read it sooner.

One chapter of the book is “The Coconut Monk,” the same essay but now updated with a short coda. Rereading it, I found it as absorbing and finely crafted as I remembered. Also, the fullness of time availed a fresh recognition of what had made it so striking all those years earlier. When the essay was first published, it was, at least to me, a way of writing a spiritual narrative that was uniquely and deeply infused with humanity. The Coconut Monk of the title was not an enlightened teacher of the kind that appears as a stock character in the all too familiar form of the seeker’s narrative—one whose every act and utterance, no matter how eccentric or unsettling, turns out, eventually, to be a lesson in wisdom. The Coconut Monk was, in John’s telling, indeed a character, and his abundant eccentricity did not need always to point to some resolution. It was sufficient to itself. And in telling his story, John writes without formulaic awe or piety. Rather, he writes with a keen irony, but it is an irony that is not cool and distant in the usual manner. This is irony that manages to accommodate affection, ambivalence, and even, defiantly, reverence.

“The Coconut Monk” was, and still is, a story worthy of its remarkable subject. It was, and still is, something wonderful.

–Andrew Cooper, Features Editor

In the spring of 1968, a few months after interviewing every Buddhist and Catholic leader in sight, a Vietnamese friend of mine told me about a large peace conference on an island in the Mekong that was hosted by a silent yogi called the Coconut Monk. I bussed the seventy kilometers south from Saigon to My Tho City with a party of novice monks. Arriving with a lot of pushing and tickling, we all climbed into sampans at the My Tho quay on the Mekong.

The river here is about four miles wide, segmenting the delta between little My Tho and Kien Hoa City. Phoenix Island was hidden by other small shreds of land that seemed to float like peach slices along with a salad of coconuts and mango, garnished and strewn together with palm fronds in the swift brown water. As we came around one of these spits of land, what I saw made me almost fall out of the boat. There, like a hallucination floating in the middle of the river, was what resembled a Pure Land Buddhist Amusement Park built on pilings. At the prow of the island, a towering pagoda rose from the top of a seventy-foot plaster mountain. The summit was crowned by a Buddhist swastika, a triangle, and a cross, which looked down on a huge terrazzo prayer circle, separated by color scheme and the elegant sigmoid line of yin and yang; duality in motion. Sporting neon lights on their heads, the nine dragons of the Mekong sprouted a full forty feet high from the prayer circle. The dragons were ancient and revered figures, symbolic of the nine fingers of the Mekong River’s alluvial fan that had in fact created the amazingly rich delta.

While we got closer, the noise of our little outboard motor began to fade and disappeared beneath the din of large wind-bells that hung from the corners of the seven-tiered pagoda. There were hundreds of them. Their size was oddly familiar though and I later learned that they were made out of the brass casings of 175mm howitzer shells. As we came around in front of the island to a landing quay, I saw an extremely large and elaborate relief map of Vietnam, fully seventy feet from end to end, suspended horizontally above the flowing Mekong. The map was complete with little toy towns and cities, mountain ranges and jungles. Sprouting out of the North and the South were pillars that were at least five feet in diameter which rose to the sky to support two ends of a rainbow bridge more than a hundred and fifty feet above the surface, with a little hut on each end.

When we finally edged up to the docking area, I saw about two hundred monks and nuns doing prostrations in the main prayer circle, bowing toward the funny plaster mountain that supported the ascending tiers of the pagoda and looked like something designed for not-so-miniature golf. In a little alcove near the top of the central plaster mountain the Coconut Monk sat grinning. Without a doubt, he was the true embodiment of the classic “Don’t Worry—Be Happy” posture that is eternally endearing and mystifying in a world gone mad.

On this particular day, the little community of about four hundred was choked with tourists and guests for the two-day peace festival. With others I made the pilgrimage up the micromountain to receive a blessing from the master. My friends introduced me as an American Buddhist. His eyebrows rose comically and he began clapping. For a silent man, he was a most communicative person. I somehow understood him perfectly when he questioned in a gesture whether or not I ate meat. I did, and he sort of unclapped and sent an attendant running down the mountain to the kitchen area. The attendant quickly returned with mangoes and coconuts. The master made me eat. He watched intently until I gobbled the juicy fruit down completely. My genuine enthusiasm was applauded by all as a sign of conversion, or at least sympathy.

I explained to the Coconut Monk (Dao Dua in Vietnamese and pronounced Dow Yua) that I was very interested in Taoism and of course Buddhism. The day before, when I had sat stoned in the Dispatch office staring at a map on the wall, I noticed that if one drew a circle around Vietnam, a simple yin-yang curve appeared. Ton Le Sap Lake (yin) in Cambodia and Hi Nam Island (yang) in the South China Sea, separated by the curved coastline of Vietnam itself, made a perfect, classic yin-yang symbol. The center of the completed visualization lay smack on the infamous DMZ.

When I told him about this discovery, the Coconut Monk’s eyebrows jumped up again and he stared at me seriously. After a very long moment, he suddenly sent another monk scurrying down to a little library in the grotto/heart of the pagoda mountain. When the monk returned he had an exquisite map of Vietnam highlighted with the exact same circle around it which Dao Dua had drawn himself the day before. He was going to release this meaningful cosmo-geographical discovery to the guests later as a kind of explanation for the Vietnamese predicament; and here this round-eye had stumbled on the same thing, perhaps picking up the master’s vibrations. It was a tremendously awkward moment. The surrounding monks and nuns started clucking their approval, and whispering to each other about my prophetic perceptions. Dao Dua and everyone began complimenting these friends who had invited me. No mere coincidence this, which had brought the American Buddhist to Phoenix Island. Within an hour of being there, I had become a sign, of what I’m not sure. Nonetheless, I was to pay for that little exchange of symbol-awareness with a mixture of pride and embarrassment for the rest of the years I was to be associated with Dao Dua, as the incident eventually spread on the Taoist tomtom circuit throughout the delta.

I didn’t see it happening at first but an increasingly deeper understanding of the life-and-death lessons of Vietnam were to be miraculously furthered by this jungle monk, whose eccentric attitude indicated a compassion and humor that made pathos and simpleminded commiseration unworkable. For me this lesson has never become obsolete.

My year in Vietnam as a soldier had left me with the memory of being a very realistic target. I was always frustrated by my army role and the desire to be near the people without my olive-drab identity. Soon I started going down to Phoenix Island every weekend on my little motorbike. I felt happy in the countryside and that I was no longer such a juicy bull’s-eye in the dress of the foreign invader. My shoulders were light as I motorcycled through the flickering sunlight on my little bike under the palms. I felt very secure with the people and as my accent got better, I began to lose the notion of what it was to be non-Vietnamese.

I was happy here. Perhaps happier than I had ever been in my life. The island became my refuge for the next five years.

On Phoenix Island, the mutual grief about the war was honest and penetrated all cultural barriers so that I felt like just one of the million carp swimming along in the silt-rich brown water of the Mekong, whose bounty travels all the way from Central Tibet to fan out here in the delta and on into the South China Sea. I was happy here. Perhaps happier than I had ever been in my life. The island became my refuge for the next five years.

Any sort of happy equipoise was Dao Dua’s play. He was the father figure I’d longed for and we forged a deep affection for each other. Inversions, centering in chaos, transmutation, and a hilarious annihilation of negativity, were seemingly possible here. An incestuous exhibition of symbols swung around on a pole in the wind. A sign pivoted there, displaying Buddha with his arm around Christ; the flip side, the Holy Virgin, Mother Mary embracing the Bodhisattva of Compassion, Quan Yin. Always, bells out of bullets, inverted aggression.

In response to this extraordinary display of concrete pacifism, and to his Harpo Marx impression of a Buddha, my commitment to the Coconut Monk grew.

One day, the Coconut Monk summoned me. He asked me to stay more permanently with him on the island. He handed me his coconut begging bowl, and I accepted. That night, in the small hours I was woken up, and all the monks took me into the large cave in the plaster mountain and handed me the maroon robes (pajamas really) of the community. Having accepted the robes and the rules of the community such as they were, I moved into a tiny hut which we built on top of an old wooden river barge.

No war and a dragon’s roar of nonaggression were the most tangible, and often mysterious part of Dao Dua’s influence. It seemed to rule the environment, and I mean this quite literally. It is one thing to emanate kindness or manage to deflate a kitchen quarrel, but there was something deeper going on here. There actually was no war, or the jagged vibrations of war on this island. Above and around it, yes. Many evenings I used to sit eating pineapple under my thatched hut in the moonlight, watching both banks of the river rage at each other with howitzer shells and tracer bullets whistling back and forth over my head, while the colored lights of Dao Dua’s prayer circle embraced the sadness and the huge bells of Phoenix Island slammed, exchanging and diffusing the suffering.

From a logical or pedestrian point of view Dao Dua was quite mad. His presentation was beyond ridiculous, though in fact he danced in a desperate political world surrounded by an electronic battlefield. He made one’s mind spin, but his style penetrated the heart. A purely analytical mind could never get purchase on his vision.

Whether or not the person you take teaching from is completely out of hand or represents the truth is often an unavoidable problem. This is more and more the case as we have to spiritually grow up and have to take responsibility for our own truth, rather than hide behind a dead doctrine or any old emperor’s new clothes. But in Vietnam, with everyone else in sight trying to slaughter each other, I found it easy to be relaxed about Dao Dua’s debatable relevance.

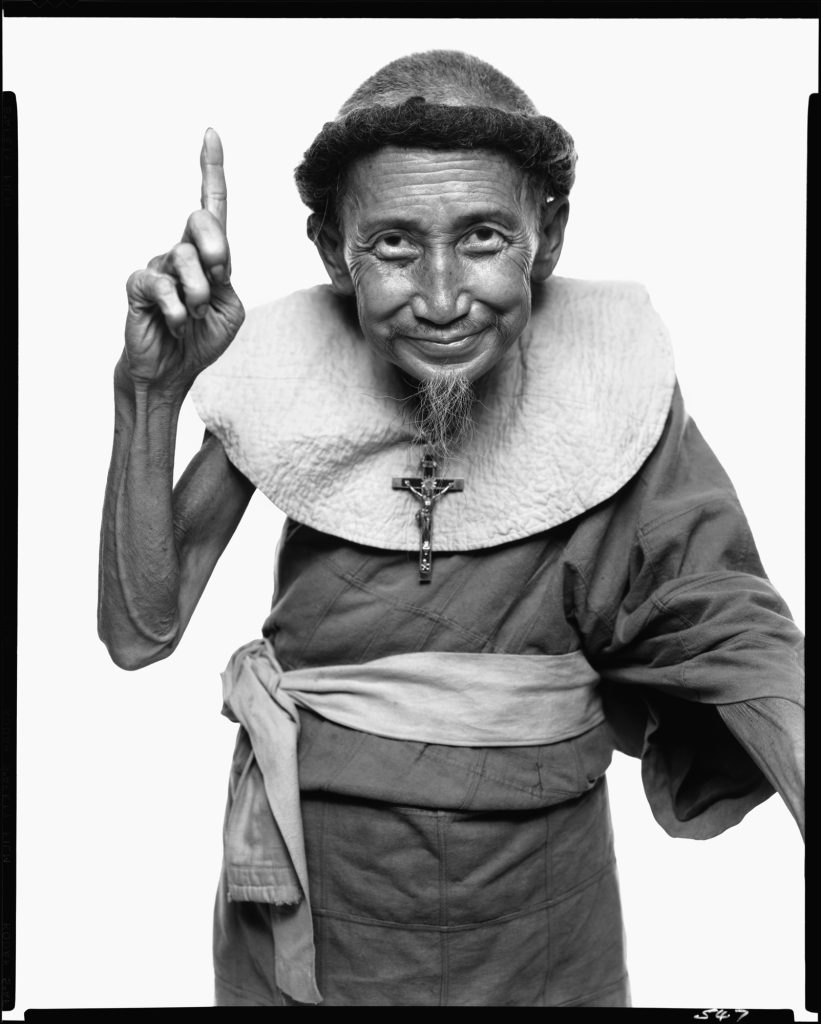

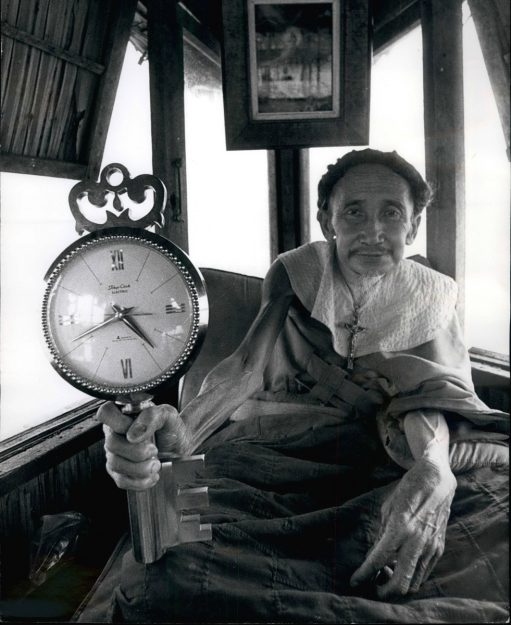

Dao Dua was the epitome of his creation. When I met him he was well under five feet tall. He used to be taller, but he had fallen out of a tree that he was meditating in and broken his back. He asked his disciples not to worry, and get him back up in his tree. His lower back became fused in a sitting posture. His arms seemed to sprout out of his chest instead of his shoulders. His expression mixed a mock-seriousness with a huge approval of everything, except the demonstration of war. The fact of it, however, didn’t faze him.

Dao Dua was special. He normally wore his ponytail wound around the top of his head with the tip tucked in at the back. He thought this could symbolize Christ’s crown of thorns. Sometimes he let the ponytail hang down in back, which he said represented Maitreya, the coming Buddha. Then again, he would pull it full around like a beard under his chin and stuff it over the far ear. This one always eluded me. Abe Lincoln perhaps? Symbols are always good advertising, but Dao Dua’s knees and the overall shape of his body reflected years of really industrial sitting practice and prostrations.

Dao Dua’s expression mixed a mock-seriousness with a huge approval of everything, except the war.

The Coconut Monk always wore a large crucifix over the saffron robe of a Buddhist monk. It rested on a large round saffron collar, similar to what a clown might wear. I’d never seen anything like it. I studiously asked Dao Dua its origin. He scribbled a note which when translated said, “It’s really a bib. I invented it. I only eat vegetables, but I always seem to spill my food.”

Having discovered the peaceful eye of the hurricane, I felt a little selfish about my niche, but Dao Dua’s generosity compelled me to invite friends from Saigon to come down and spend a few nights on the island and enjoy his peace. Most of my friends were combat photographers working for the networks and wire services. They, too, found Phoenix Island and its master the only refuge available when the succor of gallows existentialism ran dry. Quickly Dao Dua realized that he had a built-in public relations department through me and these new war-orphans. In some way the Aquarian age had delivered AP, UPI, Time and Newsweek, CBS, the BBC, and French television, as well as National Geographic, into his lap.

One full-moon night Dao Dua decided to make a move. I was awakened at about 4:00 a.m. by my friend Dao Phuc, the Coconut Monk’s only English-speaking devotee. The wind was blowing small ripples across the Mekong, and Phuc threw his cloak over me against the chill as we walked across the wide prayer circle to the plaster mountain. The morning star had risen over the river palms but the moon was still up and Dao Dua was eating his breakfast of coconuts and hot red peppers. He wanted me to go to Saigon and arrange for my journalist friends to come to lunch as his guests in Saigon’s Chinese suburb of Cholon. My motorbike was already strapped into a sampan waiting to take me to the mainland. When we hit shore I started out nervously for town. I knew that if Dao Dua were to meet his luncheon date and leave the island, he was risking imprisonment. As for myself, I was risking my visa and general credibility. In a way, it was really like being Soupy Sales’s press attaché.

I contacted everybody I had ever brought to the island, many of whom had grown to love the Coconut Monk. The lunch was a huge feast prepared and served by some of Dao Dua’s Saigon-based devotees who ran a Chinese pharmacy. Dao Dua did not appear at first, but about halfway through lunch he arrived in a 1954 Buick Century with a saffron-painted roof. Though he wouldn’t leave the backseat of his car, he handed me an outline of his plans. He wanted my friends in the media to know that on the following day he would arrive at the presidential palace, and then march up the boulevard to the US Embassy to present Lyndon Johnson’s emissaries with his updated plans for peace.

After lunch we all went our various ways. Dao Dua had disappeared in his car, leaving us all apprehensive about the mess that we knew would follow any public demonstration on the streets of Saigon. Dao Dua had managed to get off his island by meeting the car at a secluded part of the river, but his presence in the backseat of his car on a Cholon street had started a buzz through the city.

Having seen the head-smashing methods used to break up street demonstrations in Vietnam, I was worried about him. People were passionate and the police often cruel. The solution I thought was to go to the US Embassy right away and warn them that a peaceful monk wanted to drop by and deliver a letter for President Johnson. The political section treated me politely, and after informing them of the next day’s activities I left feeling that this little bit of diplomacy would smooth things over. I was very naive. The following day my friends and I rendezvoused in a side street near the palace. Everything looked fairly normal except perhaps for me—a Westerner in maroon pajamas. Dao Dua’s car came around the corner and when he stepped out, half the people on the street stopped and stared and began to giggle among themselves, or make prostrations of obeisance to the jungle holy man. The other half turned out to be plainclothes policemen, many of whom had apparently been following me since I left the US Embassy the day before. Police jeeps quickly tore in, blocking the way to the palace, so Dao Dua started strolling toward the embassy. He had brought one coconut with a naturally formed peace sign on the bottom. Actually, all coconuts have this, but he thought that there could be the outside chance that the American president might be moved sufficiently to halt the war though this lovely organic sign of universal harmony.

Our corps of friendly photographers and journalists snapped away, as the small band of ten monks and nuns made its way up the street toward the US compound. The police were actually very delicate with Dao Dua. The central command had made a faux pas by sending a captain to lead the operation whose family was from Kien Hoa where Dao Dua was most revered as a saint. In fact, the old man knew him as a boy. Anguish and confusion covered the captain’s face as he tried to persuade Dao Dua to please go home to his island and not make any trouble. Dao Dua just kept walking and grinning and as always, pointing his finger to the sky with huge approval as if complimenting the weather or heaven itself.

Helicopter gunships began circling overhead to defend US soil from my four-foot-eight-inch teacher.

As we approached the embassy, a company of marines surrounded the building and locked a huge linked chain around the main gate. As I looked up I saw about forty more soldiers on the roof with quad-barrel 50-caliber machine guns staring down at us. Helicopter gunships began circling overhead to defend US soil from my four-foot-eight-inch teacher. At this show, Dao Dua sat down on the sidewalk and refused to move. After twenty minutes someone in the embassy began to realize that a little old man was making a ridiculous spectacle out of the police and American military might, all with a single coconut.

Since the old man seemed to have half the press corps cheering him on, the atmosphere began to change into a weird sort of party. Dao Dua started preparing his lunch on the street. By this time the Vietnamese crowd, past their nervousness, were howling with laughter. Eventually, a tall and typically sweatless diplomat came out and accepted the letter through the bars of the gate. He refused the coconut on the grounds that the president of the United States could not accept gifts from foreign dignitaries. Dao Dua was satisfied and moved off. Once again with police escort, he was taken back to Phoenix Island with the threat of more severe imprisonment if he ever set foot on the mainland again. To help make the point, a raid had taken place in his absence, and thirty of Dao Dua’s closest monks were arrested.

In his letter Dao Dua had asked LBJ for the loan of twenty huge transport planes to take him and his followers, plus building materials, to the Demilitarized Zone on the Seventeenth Parallel between North and South Vietnam. There, in the middle of the Ben Hai River, Dao Dua would build a great prayer tower and deposit himself on the top without food or water. Along with three hundred monks on one side of the river and three hundred on the other, he would pray for seven days and nights. He assured the American president that this project would bring peace to Vietnam.

In the following years Dao Dua and I played many games together. I was nearly thrown out of the country on several occasions, and it was probably the aura of his wackiness that saved me. Anyway, after this first incident and test of my commitment, I don’t think I was ever really taken seriously again as a serious journalist. I, too, was transformed into a nuisance and a nutcase. Time magazine ran a picture of me in my robes with the caption:

John Steinbeck IV

A yen for Zen?

In the course of the next few years, with the help of myself and his other new friends, the Coconut Monk escaped his island many times, always to be carted right back by the police, who eventually kept a flotilla of patrol boats circling the island. A police station was established on the edge of the community and soldiers began little patrols on the island. Once in a while, US helicopter jockeys would drop tear gas in the middle of the prayer circle during prostrations, but never once did a bullet penetrate Dao Dua’s domain.

It’s all over now. Ho Chi Minh is in his grave, and so is Dao Dua. At first I heard that Dao Dua had left his island and moved back to Seven Mountains. This was in 1973. Then later in 1986, in a Vietnamese restaurant in Paris I overheard my name and his mentioned by some Vietnamese exiles. The Communists had tried to turn the island into a tourist attraction after the war. Later I learned that the Coconut Monk had been put under house arrest by the North Vietnamese and eventually killed. When I saw him for the last time we didn’t say goodbye. He touched his eye, indicating a rare tear. Then grinning, he pointed to the sky where he lived. Memories are obsolete and I can’t forget.

♦

From The Other Side of Eden: Life with John Steinbeck, by John Steinbeck IV and Nancy Steinbeck © 2001. Reprinted with permission of Nancy Steinbeck and Prometheus Books.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.