When I was five, I soaked a bucketful of pennies in blue starch. It was that kindergarten kind of starch, a magical substance. At night before I went to bed, I poured the pennies under my pillow. The plan was this: While I dreamt on top of them, God would take them for the poor in heaven.

In the morning, it was a moment or two before I remembered that a miraculous absence lay in wait for me under my pillow. I lifted the pillow up from the bed—but it wouldn’t lift. I pulled until the pillowcase ripped, the pillow came away in my hands, and then I saw it: a greenish foam of copper pennies congealed in a sour-smelling glue.

I was stunned: the blue starch, which was to be the medium of transformation, had instead become the medium of a ghastly stasis in my bed. The shiny pennies, which I had been gathering and admiring for weeks, had turned on me. Fortunately, my mother was understanding. She didn’t scold me for the ruined sheet and pillowcase, or for the mattress that had to be washed and dragged into the sun. She explained that there were no poor people in heaven and that God had no need of money.

From that morning on, there was a gulf for me between money and God. I had made a valiant attempt to become intimate with money, I had slept one whole night with it in my bed—and I’d been betrayed. I had mixed it with my soul’s aspiration, in the form of the magic blue starch, but the coins had revealed their gross material nature. Money had fallen out of grace.

When I went to church and heard “It is harder for a rich man to enter the gates of heaven than for a camel to go through the eye of a needle,” I believed. I had seen for myself that money was a dirty thing. Throughout my childhood, those smelly coins mingled with images of Jesus overturning the tables of the moneylenders, Saint Francis preaching to the birds in his brown robe and sandals, frail Bernadette of Lourdes bent under her load of sticks. As a teenager in the sixties, I easily grafted these images of Christian poverty to the bare feet, the paisley clothes, the yurt, the homemade yogurt thickening in the sun, the plastic bags hung out to dry, the backpack and hitched ride that were the modest emblems of my generation’s giant plans to save the planet. Then, discovering Buddhism at eighteen, I was drawn to yet another powerful tradition of simplicity: the monk and his bowl, the moon in his hut, the raked rock-garden, the twirling of a single flower that expressed release from the suffering of desire.

Some years ago, at a friend’s behest, I filled out a questionnaire: “What’s Your Money Personality?” Except that I answered “No” to “Would your friends be appalled at the thought of borrowing clothes from you?” I came out with the highest possible rating for the “Spiritual Poverty” type. When I read the definition of this type, I recognized myself—along with most of the friends who might borrow my clothes. For us there was a link between being poor and feeling blessed.

At twenty-nine, I married a man I met at the Zen Center in Rochester, New York. Eliot lived down the street from me, in a sort of Zen rooming house where he occupied a brown room so unadorned that once I told him it looked like the room of a blind person. The one decoration was a huge yellow moon that hung from the ceiling, a vinyl moon that he had stitched himself, using a cobbler’s awl, as one of his rare theatrical props. He was a mime. He could sit on air, talk on a nonexistent telephone, and swim without water.

After we married, he moved down the street into my house, contributing his yellow moon, his tattered clothes, and the rusted red wagon he’d had since childhood. We set our zafus alongside each other and merged our two extravagant mountains of books on Buddhism. We rose before dawn to go to the Zen Center. We returned in the evenings and on Sunday mornings, and we saved our money to attend retreats whenever possible. He performed for schoolchildren; I worked as a nanny.

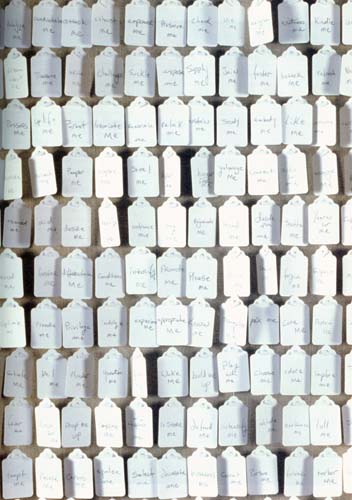

Austere? Yes—but it had its own abundance. Along with our comrades, we felt extremely lucky to be devoting ourselves to The Great Matter: suffering and liberation. This was both a necessity and a luxury to us—and there were other gifts, too. In the shared intensity of Zen practice, deep friendships flourished; in the interstices of strict discipline, wild laughter bloomed. When we weren’t sitting in the zendo or working at our menial jobs, we confessed our great Zen-gaffes, concocted lavish vegetarian feasts, and engaged in a constant potlatch-swapping of clothes, household goods, and services: one massage in exchange for two loads of fine compost, three homeopathic tinctures, four loaves of fresh-baked bread.

And now? Though Eliot and I are no longer married, we live close to each other in northern California, and our teenage daughter moves easily back and forth between our homes. Eliot rents a crooked little house that looks like a glorified chicken coop. I live in a solid little house that I managed to buy last year, having taken my first “real job” as a full-time college professor a few months shy of turning fifty. Though many of our friends from various Buddhist communities did eventually move into professional careers, an equal number remain economically marginal: they drive ancient cars, still shop at thrift stores, have bad teeth and no holdings.

Is it any wonder that most of my close friends and I completely missed the great bull market of the late twentieth century? I’ve found it strange to see those other baby boomers—the ones who tended their money—suddenly discovering spirituality. I marvel at the explosion of books on meditation, the mainstreaming of yoga, the Zen coffee mugs and calendars and Dummies’ guides to enlightenment. “Have you just discovered your mortality now?” I sometimes feel like shouting in the bookstore, as I head straight for the shelf marked “Personal Finance.”

I have no regrets about the course we took. There’s a phrase in Zen about “the fish that can be caught with a straight hook”—and I still feel incredibly lucky to have swum in that school of fish. We didn’t wait to be yanked by the barbed hook of wrinkled faces and creaking joints; we poured the freshness of our youth into the quest to find out where do we come from and where are we going? Sometimes, however, when I think of the lack of concern that my companions and I had for money, it does seem a kind of hubris to me, a blindness to a particular kind of karma, to certain laws of cause and effect. I have come to a belated admiration for people who have truly made their way in the world, to an appreciation of the discipline it took, the generosity it makes possible.

Recently I even tried an experiment. I put a small handful of coins under my zafu, the same red and purple zafu I’ve had since I was eighteen years old. Then I sat on it. It felt weird, as though I might get bucked off at any moment, but I gritted my teeth and continued. I knew that I just had to sit with the weirdness, the feeling that I was somehow desecrating the seat of meditation—but it was hard. When my timer dinged, I lifted the cushion up, and there were the coins. Neither gloriously absent nor disgustingly present, they were just sitting there, as inherently blameless as anything else in the universe: a bird, a rock, a blade of grass. I gathered them up and put them back in my wallet—the red wallet that a friend bought me recently to attract prosperity—and it struck me that perhaps I was beginning, just beginning, to walk the Middle Way.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.