Let’s try an experiment.

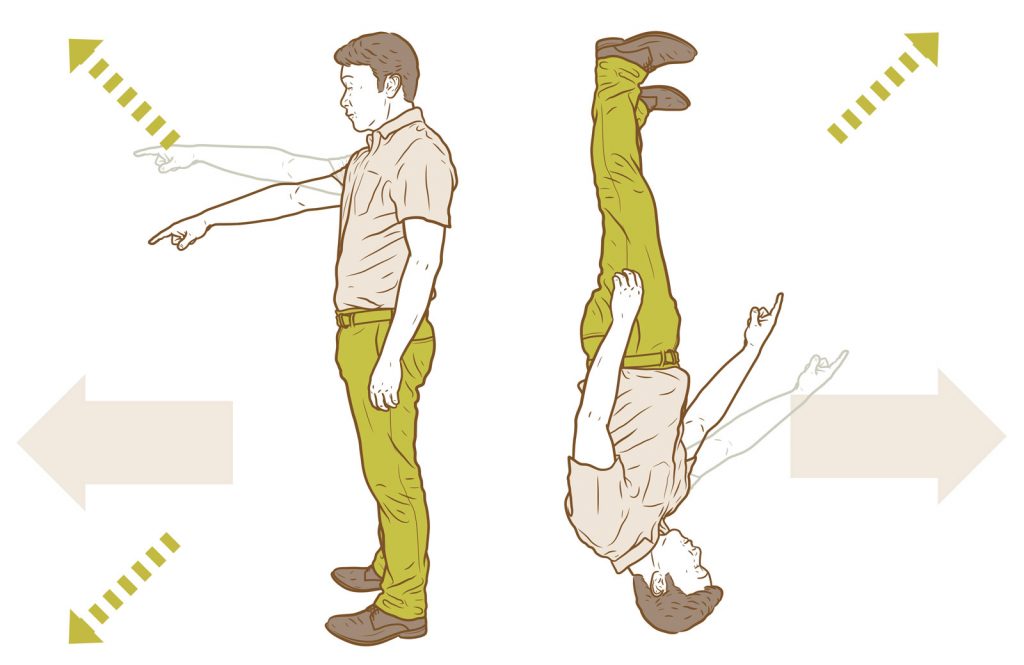

Point at something across the room—perhaps a table or a chair—and pause to really notice what you’re pointing at. Then point at the floor in front of your feet and take that in. Next, point at your belly. Finally, point your finger toward your face. What do you see? Is it what you’re pointing at?

For many, this exercise is a revelation. Our head, presumed to be the locus of thought, memory, and sensation, is missing. Instead, it appears as though we are wearing the world on our shoulders. In this vivid centerlessness, the boundary between “inside” and “outside” may dissolve—along with the usual sense of self-as-experiencer.

The pointing experiment, childlike in its simplicity, is a hallmark of the Headless Way, a method devised by the British philosopher Douglas Harding (1909–2007) to help acquaint people with their true nature. Harding was not a Buddhist, but he was convinced that his insight resembled the sudden awakenings described by Tang dynasty Zen masters, a connection he explored in his most popular book, On Having No Head: Zen and the Rediscovery of the Obvious (1961).

Harding wrote and lectured tirelessly, teaching workshops well into his nineties. Since his death in 2007, Harding’s legacy has been carried on by Richard Lang, a Cambridge-educated psychotherapist who has led the Headless Way workshops around the world, including several with American Buddhist sanghas. Harding’s empirical and avowedly nonhierarchical approach has also been touted by Buddhist-adjacent thinkers such as Ken Wilber, Sam Harris, Thomas Metzinger, and Susan Blackmore.

The pointing exercise and Harding’s other experiments call to mind Zen instructions to “take the backward step,” “see one’s original face,” or “trace back the radiance.” At the same time, these exercises seem to stand in stark contrast to traditional Buddhist teachings that say the breakthrough to enlightenment requires many years (or many lifetimes) of arduous practice under the tutelage of a recognized teacher. One does not need special training to learn Harding’s techniques. They are easy to perform and available for free on the Headless Way website (headless.org), where people are encouraged to try it for themselves.

Given that low barrier to entry, committed Buddhist practitioners might wonder whether the Headless Way is too good to be true—and whether it offers authentic insights.

In Lang’s view, it’s all rather straightforward.

“When I do workshops, I start with the experience, right from the beginning, because then we’re equals,” Lang says, speaking via Zoom from his home in London. “Can you see your head? No. Can you see the world instead? Yes. You’ve got it.

“The more you accept that people have got it—which they have—the easier it is for them to get it. [Getting it] is the easiest thing in the world. Living from it is more challenging.”

Lang has been seeing his no-head since he was a teenager. In 1970 he and his brother attended the London Buddhist Society’s summer school, where they met Harding and were introduced to his experiments. Before long, Lang was sharing the Headless Way with others. “I somehow felt I’d been born to do this,” he says. Later, Lang spent four years living at a Theravada practice center in Cambridgeshire, where he led ten-day meditation retreats. But this, too, became an exploration of the headlessness: “In a way it was an opportunity for me to be still and quiet with the Headless Way.”

Harding, who by his own account was painfully shy as a young man, was raised in a strict Christian sect called the Exclusive Brethren, an experience that left him with a healthy skepticism of spiritual authority. He left the group as a young adult and embarked on a career as an architect, but all along he was deeply preoccupied with the question of identity. “Douglas was asking the question ‘Who am I?’ ” Lang says. Then he came across an arresting self-portrait sketched by the Austrian physicist Ernst Mach that depicts the side of Mach’s nose, his torso, legs and the room in which he was sitting. “When he saw it, he said, ‘Oh, OK, that’s from my point of view,’ ” Lang says. “He knew he had struck gold.”

The headless experience is the point at which we are zero distance from ourselves.

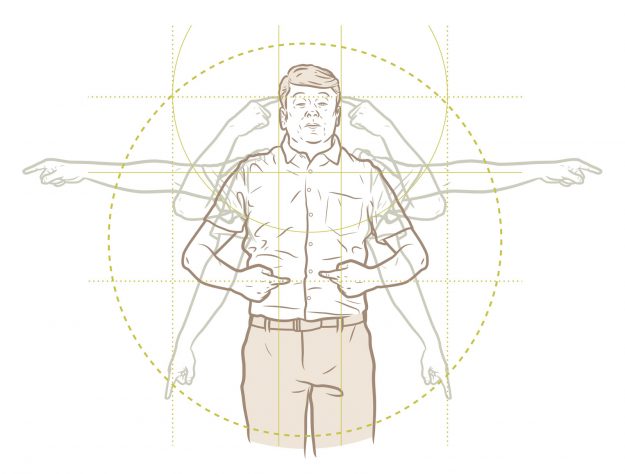

Harding had a scientific turn of mind and sought an empirical basis for reconciling what he had experienced with the startling insights of 20th-century physics. He eventually worked out a schema that said our identity depends on the distance from which we are regarded. Viewed from outer space, we are infinitesimal. Up close, we loom large. And at the subatomic level, we’re mostly empty space. The headless experience is the point at which we are zero distance from ourselves—and where something interesting happens. The customary view of self-as-object has gone missing, and all that’s left is the world. Inside becomes outside, and outside becomes inside, the nondual perspective described by the Zen ancestors. But at the time Harding knew nothing about Zen.

“He came across this independently of any tradition: ‘What I am depends on the range of the view,’ ” Lang says. Harding had his insight while working in India in the 1940s, and he labored for ten years to express his realization in the massive work The Hierarchy of Heaven and Earth, first published in Great Britain in 1952 by Faber and Faber, with a foreword by C. S. Lewis. In the late 1950s, Harding encountered Zen through the writings of D. T. Suzuki and became acquainted with the teachings of Huang-Po and other Chinese Zen ancestors. “He had not really shared the Headless experience with anyone, and so when he came across Suzuki, which led him to people like Huang-Po, he felt he had at last found friends,” Lang says.

Harding’s piqued interest in Zen led him to eventually meet Christmas Humphreys, founder of the London Buddhist Society, who agreed to publish On Having No Head. Harding went on to teach at the society’s summer school until 1975, when his relationship with the institution came to an abrupt end during one of their gatherings.

“Christmas Humphreys was kind of a slow, long, gradual-path guy,” Lang explains. “Humphreys rather pointedly said to the audience, ‘There are some people here who think you can get it straightaway. You can’t—you can’t get it in this lifetime, you can’t even get it in the next lifetime.’ Well, that was the end for Douglas.”

As Harding’s writings gained a wider audience, Western Buddhist teachers were intrigued by what he had to say. One was Roshi Philip Kapleau, the American author of The Three Pillars of Zen, who had trained in Japanese monasteries for 13 years before founding the Rochester Zen Center in New York. Kapleau was an admirer of Harding’s and visited his home, telling a friend, “ ‘Douglas’s house is the spiritual center of England. What’s going on here is great,’ ” Lang says.

Harding went on to pay several visits to Rochester, Lang says. Things went awry on a second visit, however, when Kapleau encouraged his students to subject Harding to some rough-and-ready Zen testing. “A monk came on the stage and pulled his nose, and Douglas said, ‘Look, I didn’t come here to be tested. I’m a friend. I came to share something.’ It was a clash of an old tradition and a man who wasn’t in the tradition.”

Harding also befriended Ajahn Sumedho, the American-born Theravada Buddhist monk who established the Amaravati Buddhist Monastery in South East England, and some of his students. And John Toler, an American Rinzai Zen priest living in Japan, also sought Harding out after hearing about headlessness and went to visit him at his home in Nacton, Suffolk. “John was generous and he had no doubt: ‘You see this and it’s self-evident,’” Lang says.

Harding “had a great debt, in a way, to Buddhist friends and to those old Buddhist teachers,” Lang says, “but he did make a progression, and after two or three years he realized that the Headless Way was not Zen—it was its own thing. He had to work that out, because it was so close to Zen. And yet he just had to say, ‘Well, this is something new, and it stands on its own, and it doesn’t need to be under another umbrella.’ ” The two paths shared a family resemblance, it seemed, but they were distinct.

Harding “had a great debt to Buddhist friends and teachers.”

In 1996, Lang cofounded the nonprofit Shollond Trust to carry on Harding’s work. Through Lang’s online and in-person workshops and annual gatherings in the UK, US, and Australia, Harding’s ideas have gained a wider audience in recent years. And influential figures like Sam Harris, who interviewed Lang for his popular Making Sense with Sam Harris podcast and asked him to develop content for his Waking Up app, have brought even greater attention to Lang and Harding.

The Headless Way also caught the attention of Robert Beatty, a former Theravada monk who leads the Portland Insight Meditation Community. “Three or four years ago he emailed me out of the blue and said he loved the Headless Way,” Lang recounts. “There are some unusual characters who are deep in their tradition and yet find the Headless Way and go, ‘That’s great. Let’s bring that in.’ The truth comes before the tradition.”

Around the same time, Hwalson Sunim, founder and abbot of the Detroit Zen Center, encountered Harding’s writings while searching for ways to better translate Zen for students in the West. Myungju Sunim, the center’s vice abbot, said Hwalson realized that Harding “had an experience of awakening without being connected to a lineage, and the language that he expressed it with was uniquely Western.”

Myungju recalls one of Lang’s workshops that he gave in Detroit in April 2019. The atmosphere was light, even playful, as Lang led a group of around 40 people through assorted exercises, like having two partners peer into opposite ends of a paper tube. “You’re looking at another person’s face, and it’s very intimate,” she says. “It’s a little scary. And while you’re in this tube, feeling like you’re ridiculously 5 years old and someone is saying, ‘Now, you’ve traded faces. You actually don’t have a face.’ … [That experience] allowed for an intimacy at the Zen center that was very beautiful.”

She adds, “It’s the practice of true seeing, and it’s very unfettered. But I think Richard and Douglas would be the first ones to say, ‘This is just a starting point.’ ”

The headless way would seem to share with Zen the aim of eliciting a direct realization of a world-without-self—but it more or less stops there. Zen, arising within a monastic Buddhist tradition, prescriptively addresses ethical and metaphysical questions and requires a teacher to authenticate a student’s insights. Traditional Zen practice is a rigorous body-mind discipline, famously presented as a life-and-death matter demanding unrelenting spiritual exertion. As the 18th-century Rinzai Zen teacher Hakuin Ekaku memorably put it, “Should you desire the great tranquility, prepare to sweat white beads.”

Headlessness, by contrast, is resolutely nonhierarchical—Lang refers to fellow practitioners as “friends,” not “students”—and assumes that those who experience headlessness can interpret it for themselves. It offers a straightforward and relatively undramatic method for appreciating what has always been the case: that we never directly perceive our heads—or a separate self. Remembering to see it takes effort, but it can be transformative.

The deeper implications of that seeing elude many people who try Harding’s experiments, Lang acknowledges, and some simply shrug and move on. “My approach is just to keep affirming that the person has gotten the experience and that their response is totally valid,” he says.

Myungju thinks that headlessness may be best suited for those who already have a serious meditation practice and a context within which to appreciate the experience. “The one weakness, if there is one, is if it tries to stand on its own as a lineage without a context for community and practice,” she says. “The greatest pitfall might be thinking, ‘I don’t need a teacher, I don’t need a community, I don’t need a practice—my practice is to just sit here and point at my head.’ ”

Despite the differing approaches, Headlessness could help guide dedicated practitioners toward an initial awakening. But what comes next is a different matter. In the end, perhaps the best perspective comes from the Buddha himself, whose admonition to his monks in the Cunda Sutta (SN 47.13) placed matters squarely in their hands: “Be islands unto yourselves, refuges unto yourselves, seeking no external refuge; with the dhamma as your island, the dhamma as your refuge, seeking no other refuge.”

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.