Oryoki, often translated as “just the right amount,” is a highly choreographed ritual of serving and eating food—a ceremonial dance of giving, receiving, and appreciation. It is a practice that was codified in China during the T’ang dynasty and was the model for the sweeping grace of the tea ceremony. Practiced, with a few variations, throughout the Zen schools, it was also adopted—in America—by Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche, the Tibetan founder of the Shambhala lineage. Practically speaking, it is perhaps the most efficient, aesthetically pleasing, and least wasteful way to feed a large group of people sitting in a meditation hall, or a single person at home for that matter. Yet more specifically—and arising from Zen’s insistence on blending the sacred and the mundane—oryoki unifies daily life and “spiritual practice.” It is essentially a state of mind, a way of being.

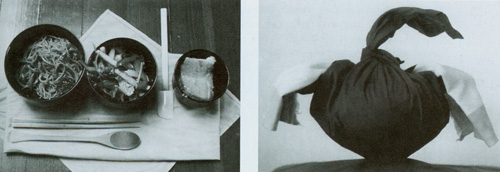

Oryoki practice uses a jihatsu, a set of nested bowls: a Buddha bowl, or zuhatsu, containing three or four smaller bowls tied in cloth with a topknot resembling a lotus flower. The set also contains—in a narrow cloth pouch—a wooden spoon, a pair of chopsticks, and a small spatula-like utensil called a setsu, which is used to clean the bowls. The outer cloth, when untied and refolded in an exact manner, doubles as a place mat upon which the bowls are laid in a prescribed sequence. To complete the package, there is a regular-sized cloth napkin and a smaller cleaning towel used to wipe the bowls dry after they are filled with hot tea or water and scraped clean with the setsu.

Related: Just the Right Amount

Participants sit in a meditation posture and wait to offer their empty bowls as the servers bring food and, in a series of hand gestures (beyond the chants of dedication and appreciation, oryoki is practiced in silence), fill the bowls to the requested level. The ecology of oryoki is complete: there is no waste. Participants are urged to take just the right amount of food—not a crumb should remain. The cleaning liquid, after it is used to wash each bowl, is partially drunk and the remainder collected and distributed in the garden. Each movement of oryoki is compact, subtle, and designed to unfold in harmony, demanding meticulous awareness to what is happening in the moment.

For beginners, stepping into this dance can be terrifying. The Zen practitioner and author Lawrence Shainberg writes of his early encounter with oryoki in his book Ambivalent Zen: “The harder I try, the clumsier I get. Rational it may be, but the ritual seems a nightmare now, one more example of Zen’s infinite capacity to complicate the ordinary.” Oryoki tales abound in Zen. I’ve seen students take too much food (a classic mistake) and then stuff the extra down the sleeves of their robes when they realize that they’ll never finish in concert with the group. Servers have spilled food on people’s heads, bowls have gone flying, minor food fights have erupted, and giggling fits have swept like wildfire through the zendo.

Oryoki is not about living some altered state of sustained “perfection,” nor is it about performance, or even detail—it is simply our lives. Oryoki subtly and steadfastly exposes the patterns and sticking points of our minds and our behaviors. As Zoketsu Norman Fischer, senior dharma teacher at the San Francisco Zen Center and founder of the Everyday Zen Foundation, says, “The intensity of oryoki practice is such that you get to see your own tendencies in relation to eating and serving a meal. Someone eating can ask for too much food, and a server can give too little—greed and stinginess arise. Oryoki practice develops kindness and clarity and the sense of not overdoing or under-doing anything. It teaches smoothness and efficiency and the sense of acting with a good heart.”

Once the initial clumsiness wears off, oryoki can become a wonderfully vital part of Buddhist practice. The form of oryoki, though controlled and precise, can be seen as formless—it is merely a container into which we pour ourselves. Sensei Pat Enkyo O’Hara, abbot of the Village Zendo in New York City, pointed to this when she told me, “I can remember one time looking down at my cloth and my bowls and seeing what a mess my mind was. They were all over the place. It was writ large right in front of me, the exact state of my mind in the moment, and I love that because it’s so transparent.”

We bring to oryoki all that our mind contains, yet because our body has very specific things to do—bowing, chanting, placing the chopsticks just so—it is very hard for our crazy and distracted mind to stay stuck in any one place. Natalie Goldberg, longtime Zen practitioner and author of Writing Down the Bones and other works, picked up on this when she told me, “I loved oryoki—something finally had order.”

Oryoki is liturgy. It makes visible the invisible. Hakuyu Taizan Maezumi Roshi, the late founder of the Zen Center of Los Angeles and a seminal figure in American Buddhism, often underscored this point. In one of his talks compiled in the book On Zen Practice, he states, “But we need not think that we are speaking only of eating bowls when we mean oryoki. More fundamentally, oryoki is just the Tathagata’s container [the “Tathataga,” or “thus-gone,” is an epithet for the Buddha]. We can appreciate everything as the container of the Buddha. We are oryoki ourselves. Not only us, but also the Buddha’s image. Candle holder, vase, bowing mat, floor, ceiling—each contains everything completely. It is all oryoki.”

The roots of oryoki trace back to the time of the Buddha and the wandering mendicant monks who possessed little more than their robes and begging bowls. The robes symbolized the external (clothing and shelter), the bowls symbolized—through the taking of food—the internal. To this day the robe and bowl are handed from Zen teacher to student as the central symbolic act of dharma transmission. Taking just the right amount of food, as the Buddha discovered, is essential to practicing the middle way of Buddhism. In the Vimalakirtinirdesha Sutra it is said that “when a person is enlightened in their eating, all things are enlightened as well. If all dharmas are nondual, the person in their eating is also nondual.”

As Buddhism moved from India to China, certain cultural influences shifted Buddhist practice. In China, beggars were generally disdained, so the days of wandering mendicant monks came to an end. Monks were encouraged to work. Monasteries were built, and group meditation, not solitary practice, became the norm. Suddenly there were large numbers of mouths to feed, and an efficient and timely system of meal-taking arose as part of a set of rules to regulate the lives of Buddhist monks.

Much of this system still thrives in Zen monasteries today. Master Dogen Zenji, the thirteenth-century Japanese mystic and seed planter for Zen’s Soto school, encountered these monastic rules during his four-year stay in China. When he returned to Japan, he refined the rules, instilling in them his meticulous attention to detail and profound insight. Meal-taking, under Dogen, became oryoki. Dogen writes, “At the very moment when we eat, we are possessed of ultimate reality, essence, substance, energy, activity, causation. So dharma is eating, and eating is dharma.”

Dogen makes it clear that the primal act of eating, our desire and need for nourishment, and the sensuousness of food are in no way opposed to spiritual practice. Oryoki is not about denial. In Thank You and OK, David Chadwick’s 1994 memoir of a four-year stay in Japan, he writes, “The use of oryoki . . . intensifies the experience of eating. It zooms one in on the victuals. In keeping with the teaching of just sitting, just working, oryoki encourages us neither to jump at the meal nor to deny it. Just eat it and just enjoy it.”

We must also remember that when we eat we take life. John Daido Loori Roshi, abbot of Zen Mountain Monastery and founder of the Mountains and Rivers Order, writes in his book Celebrating Everyday Life, “But oryoki is not just a prescribed form of ritual. It is a state of mind. It’s not about chanting and bowing and bells. It’s a state of consciousness. Because food is life, it is of utmost importance that we receive it with deepest gratitude. When we eat we consume life. Whether it’s cabbage or cows, it’s life.”

During oryoki, when we recite the meal gatha, or chant, we are showing our gratitude for both our practice and the labor and sacrifice that bring us our food. Oryoki is gratitude. And for this reason oryoki is not just a practice performed in the meditation hall. “What I like most about oryoki is the way it influences how I serve myself oatmeal in the morning here at home. It’s a sense of appreciating through awareness,” said Sensei Pat Enkyo O’Hara. Zoketsu Norman Fischer concurs: “Of course I don’t use any of the rituals if I’m not eating oryoki, but the feeling is there and the feeling gets into the body, into the heart, and into the mind.”

Oryoki, though it appears to be complex, is really not that complicated. Whether practicing it at home or in the meditation hall, we should just do it as simply as possible. As David Chadwick told me, “I think it’s good to eat silently but not to make a trip out of it.”

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.