This past spring I fell into the lovely habit of sitting on my fire escape at dawn with a pot of black coffee and The Roaring Stream: A New Zen Reader, an anthology published in 1996, edited by Nelson Foster and Jack Shoemaker. Each chapter in the book introduces a famous master from China or Japan and provides excerpts from his most significant writings and lectures. I began jotting down poems in response to the lines, images, and metaphors that I encountered—one poem per chapter, one chapter per morning. It was an enjoyable, aimless exercise, and it was exciting to see what my own mind did when allowed to build upon the wisdom of the ancients, using scraps of their language as a foundation. (Of course, I am neither ancient nor wise, only caffeinated.)

As the spring progressed and I worked my way deeper into the history of Zen, I settled on the idea of making a poem for each of the 46 profiled masters. After about 20 poems, though, my library copy of The Roaring Stream was due back, and the next person to check the book out lost it. Ha! Transience! I told a friend about my predicament and he suggested I go out and buy myself a copy—apparently the quirky beauty of the situation escaped him. I suspect that one day the dawn will find me back on the fire escape, my pencil running wild on the blank white page, old men in robes looking over my shoulder. Until then, here’s a brief selection from what I’ve taken to calling “Eddies in the Roaring Stream.”

–Leath Tonino

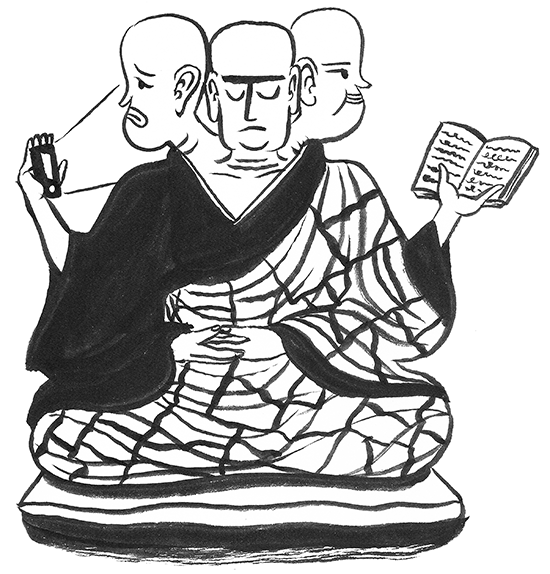

Chao-chou

(778–897)

we’re all on the job

all the time,

moving materials, staging supplies,

trying not to trip

on uneven ground slick with spring rain,

building houses, bridges, cities,

building a world on top

of the world,

half-blind, always looking left.

and to think some of us

live 120 years

carrying a board

on our right shoulder,

balancing it

on the bone.

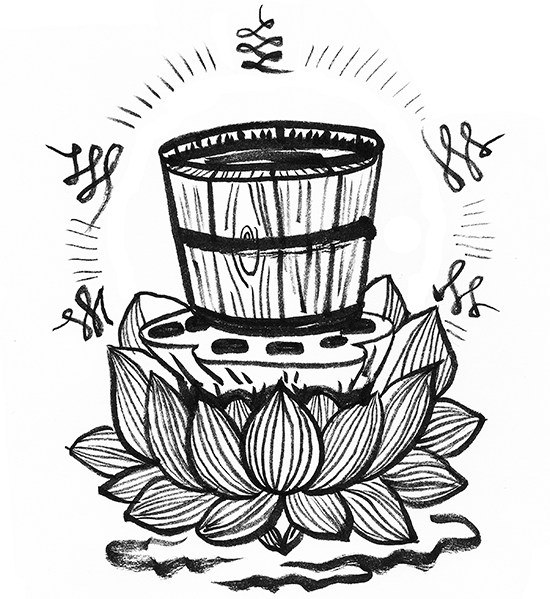

Hsueh-feng

(822–908)

dumb as a bucket,

they say,

but I say hear the bucket

speak, its voice

full of water, full of air,

emptied then brimming

with river, with rice.

who wouldn’t want to be

a bucket like this?

good for carrying, good

for spilling, never hungry

but always eating,

talking with its mouth full.

Ts’ao-shan

(840–901)

three cups of wine and still thirsty,

the drinker doesn’t know

the drink has set in

until standing up

his legs swerve left

and he falls right,

reaching out for a wall,

a friend, something

that isn’t

there.

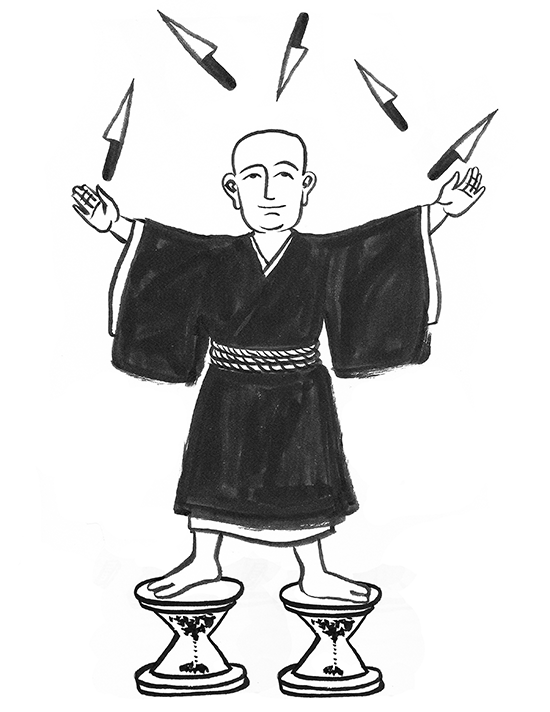

Fa-yen

(885–958)

when we say yes

or no, this

or that, without

having first traversed

mountains and seas

in searching,

that is five knives

leaving our hands,

flashing silver

in the sunlight,

and us

calling

the moment

juggling.

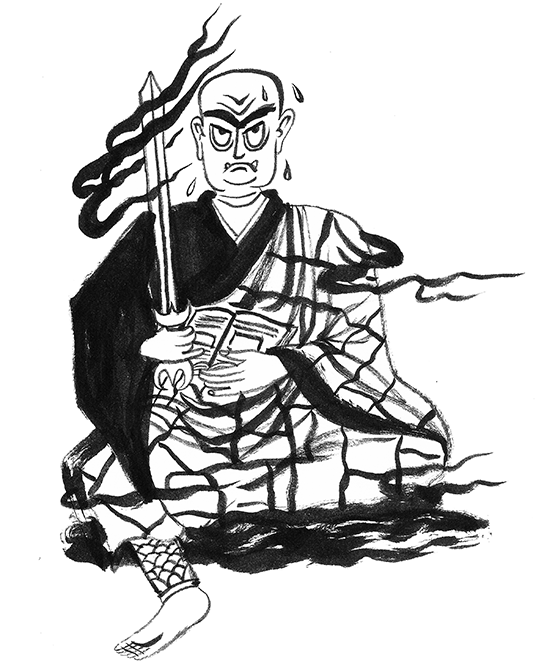

Ta-hui

(1089–1163)

love of finery, sloth, status-seeking,

evil of all kinds, we face

these as a warrior faces

his war, his fate,

riding straight at them

on a slow donkey

loaded with books

and bread.

Dogen

(1200–1253)

pretend to laugh

and you will come to laughing.

pretend to cry

and you will one day weep.

sit long enough

and you will lose your legs,

won’t stand,

won’t ever walk again.

this is a good thing.

it gets you where you’re going.

Enni Ben’en

(1202–1280)

having committed a crime,

the thief makes his getaway

in muddy socks,

thinking because he’s ditched

his shoes

he can’t be tracked.

had he only locked himself

in the safe

and eaten the money

we’d still be on the case today.

Keizan

(1264–1325)

head in the toilet, scrubbing.

no brush, no rag, no sponge.

scrubbing with thoughts, schemes, dreams

of the spotless.

driving

these hard against the hard

ceramic bowl.

what’s cleaning what?

who’s cleaning

who?

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.