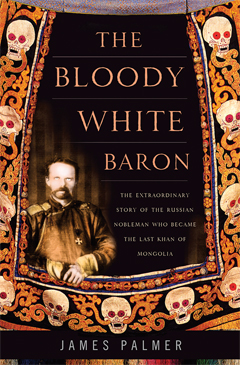

The Bloody White Baron: The Extraordindary Story of the Russian Nobleman Who Became the Last Khan of Mongolia

James Palmer

New York, NY: Basic Books, 2009

288 pp., $26.95 cloth

On the flat Earth of the imperial imagination, most anything is possible. Constraints of geography and time do not limit fantasies of conquest so much as they arm them with rich and varied paints for a worldly canvas. But the many sprawling empires of history, whether Mughal, Japanese, or British, have not arisen easily or overnight. While the unending struggle for dominion may appear in the historical record as so many moves on a chessboard, each pawn’s final farewell is much less graceful in real life.

On the flat Earth of the imperial imagination, most anything is possible. Constraints of geography and time do not limit fantasies of conquest so much as they arm them with rich and varied paints for a worldly canvas. But the many sprawling empires of history, whether Mughal, Japanese, or British, have not arisen easily or overnight. While the unending struggle for dominion may appear in the historical record as so many moves on a chessboard, each pawn’s final farewell is much less graceful in real life.

James Palmer’s The Bloody White Baron, a debut work of popular history shortlisted for Britain’s John Llewellyn Rhys Prize, exhumes a historical figure who ended up as a casualty of his own grand scheme: a man who dreamed up a new world order and then chased it across the desolate steppes of northern Asia only to meet his own miserable demise. With this biography of Baron Roman Nikolai Maximilian von Ungern-Sternberg, Palmer unearths an easily forgotten episode in early 20th-century Eurasian geopolitics. As the Baron’s story unfolds, the margins of both history and human psychology take center stage in a work that unravels more comfortable accounts of modern nationhood and spirituality.

At first take, there is nothing especially unusual about Ungern’s military life. A minor aristocrat by birth, he rose through the ranks of the counterrevolutionary White Russian army to assemble his own cavalry and briefly conquer Mongolia. It was the Baron’s motivations that distinguished him from any number of sword-wielding European contemporaries— he mounted this eastward crusade in the name of Buddhism. In a short-lived but hugely violent campaign to win a kingdom from which to overthrow the Bolsheviks, Ungern sought to reestablish a monarchical order that he would follow to the Pure Land or death.

Ungern was born in Austria in 1885, to a German mother and an Estonian father of German heritage. Upon his parents’ divorce, the boy was sent with his father to Estonia, then a part of the vast Russian empire. There, his privileged childhood as a son of marginal nobility seems to have been lonely, filled with war games and punctuated by a string of school expulsions. Palmer’s description of the youthful Ungern is unsettling: “I imagine him not to have been a bully as such, but, as his later behavior suggests, rather one of those pupils of whom even the bullies are afraid, the kind who violate the unwritten rules of childhood fights, whom nobody wants to sit near, and who cannot be trusted with compasses or scissors.”

Unsurprisingly, Ungern jumped at the chance to fight for Tsar Nicholas II in the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–5. The tall, athletic soldier reveled in the violent clashes and ascetic discipline of the trans- Siberian cavalry campaigns. Upon Russia’s overwhelming defeat by the Japanese and the popular rebellion of 1905—including the infamous Bloody Sunday, when the Imperial Guard gunned down demonstrators in St. Petersburg—something in Ungern clicked. As the monarchic order spiraled downward, he saw that a reversal of fortune for the upper classes would require more than young blood to contain the uppity peasantry: it called for the rise of a new order to resurrect the old.

Like many upper-class Russians at the time, Ungern dabbled in various spiritual philosophies inspired by Eastern religions and occultism. Although nominally Lutheran, he had connections to the Theosophical Society of St. Petersburg, and while little is known about his motivations or involvement, Palmer tells us that he subscribed to an “esoteric Buddhism.” The notion of an Eastern “Yellow Peril” that had exploded in 1890s Germany worked wonders on Ungern’s worldview. He caught the bug, but his spiritual investment in “the East” turned it upside down: in his campaign, the “Asiatic hordes” would play the role of heroic ally and redeeming counterbalance, an otherworldly answer to the pleas of the floundering aristocracy.

The Baron’s alchemic mix of spirituality and anticommunist passion inspired his storming of Mongolia. He assumed the role of Shambhalan savior from the north, charging to defend the Bogd Khan (Holy Emperor)—Mongolia’s Buddhist political figurehead—against the recently vanquished Chinese and growing Bolshevik and Japanese threats. When Ungern won Urga, the Mongolian capital, in 1920, he took the religious inheritance no less seriously than the political, declaring himself a reincarnation of the Fifth Bogd Gegen (Holy Shining One). The swastika-emblazoned ruby ring he wore, a gift from the Bogd Khan, was important to him for both its anti- Semitic and its Buddhist symbolism.

But the Baron’s prejudices were strategically narrow in scope. In the attack on Mongolia, he enlisted a broad range of help: his brutally disciplined White cavalry included Japanese, Mongolians, White Russians, Cossacks, and Buriats (Mongol Buddhists of Siberia), many of them forcibly conscripted.

Palmer picks up on the historian Isaiah Berlin’s idea that individuals born on the fringes of great empires are prone to “borderlands syndrome.” He situates the Baron in a lineage of iron-fisted rulers—including Na poleon (Corsican), Hitler (Austrian), and Stalin (Georgian)—who have fallen victim to what Berlin characterizes as “exaggerated sentiment or contempt for the dominant majority, or else over-intense admiration or even worship of it.”

This view, however, places the burden of history on a few small souls, and The Bloody White Baron, like many biographies, often seems to be doing just that. In the unrelenting parallels to Hitler that Palmer offers as evidence of Ungern’s world-historical significance, the Baron’s “hunger for power” looms larger than life—and indeed, larger than history. Still, the depth of that hunger is intimidating.

In taking Ungern’s devious fantasies seriously, Palmer offers more than an inventory of military excursions. Working with the sparse historical knowledge of the Baron’s shaky psychological moorings and spiritual pursuits, he illuminates the malleable imagination of power, to which Buddhist politics have never been immune. One of Ungern’s most powerful allies was the 13th Dalai Lama, who, fearing communistinspired revolution in Tibet, sent troops to fight for the White cause. (Following the British invasion of Tibet in 1906, the Dalai Lama fled to Mongolia, where he coexisted tenuously with his religious equal, the Bogd Khan.) But the growing Red Army was too powerful even for this alliance. After a Bolshevik defeat that all but sealed his capture, Ungern veered south. His plans for a modern Mongol empire dashed, he plowed ahead, bedraggled troops in tow, toward the last destination in his deranged grasp at spiritual significance—the towering Himalaya. Eventually, betrayed by his own men, he was executed in 1921.

Baron Ungern-Sternberg was undoubtedly psychotic, but he was also human, and his terrible schemes were informed by the most basic assumptions of the culture he grew up in. Easy as it is to dismiss him as the putrid reminder of a barbarous past, the exotic representations of the East that drew Ungern to Mongolia continue to appear in all sorts of Westernized spiritual practices. And as Donald S. Lopez, Jr., reminds us in his groundbreaking book Prisoners of Shangri-La, romanticized misinterpretations of Tibetan Buddhism—and Buddhism generally—are a burden to the individuals expected to uphold the mirage of Oriental authenticity. The Bloody White Baron serves as a warning against clinging to such projections too dearly.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.