In 1992, a forty-one-year-old Chinese man named Li Hongzhi revealed that he was the heir to a spiritual tradition that combined elements of Buddhism, Taoism, and other philosophies. He called his system Falun Gong. Fa is a Chinese translation of the Sanskrit word “dharma,” meaning Buddhist teachings. Lun means a wheel or turning a wheel. Falun is thus the dharma wheel, a metaphor for studying, practicing, and spreading Buddhist teachings. However, Li takes this one step further. The dharma wheel, the falun, is an energy center within the lower abdomen. It cannot be seen with the physical eyes but only with the “heavenly [spiritual] eyes” because it exists in another “space,” a subtle, invisible dimension. Gong means “a skill” and is often short for Qigong (pronounced “chee gung”), the skill of cultivating healing energy (qi) to enhance well-being. Thus Falun Gong means “a method of Qigong that turns the dharma wheel.” Alternately, Falun Gong is sometimes called Falun Da Fa, the Great Method (Da Fa) of Turning the Dharma Wheel (Falun).

Falun Gong consists of a series of specific standing, moving, and seated exercises, all very gentle and easy to learn. The belief that one can perceive an energy wheel revolving in the lower abdomen is not unique. T’ai Chi students commonly practice a Qigong exercise called dan tian nei zhuan, “internal rotation of the abdominal energy center,” to generate subtle coiling and turning movements in the lower abdomen, as though a small sphere is revolving behind the navel. As in Falun Gong, the goal of this practice is to harmonize the student’s qi (life energy) and consciousness with the forces of the universe.

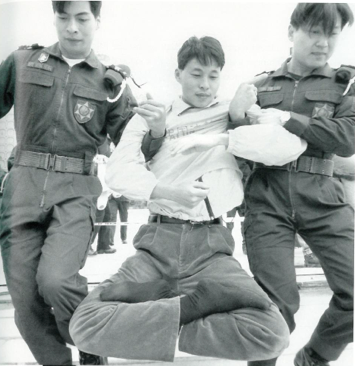

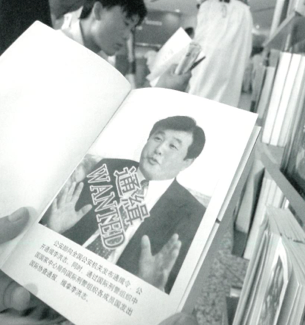

Why, then, all the political hoopla about another style of Qigong, an art that has been around for more than three thousand years? Why is Falun Gong the subject of international politics and controversy? Here’s the simple answer: Falun Gong has become a social movement. Li Hongzhi, who now lives in New York City, has at least 70 million followers, 10 million more than the Chinese Communist Party. China considers Falun Gong a “threat to social stability” and has prohibited its practice. Meanwhile, Li Hongzhi is on China’s “most wanted” list. The Chinese government has destroyed all Falun Gong promotional literature, videos, and publications and has arrested numerous followers. On December 26, 1999, Beijing courts issued seven- to eighteen-year prison sentences against four Falun Gong leaders after a one-day trial. China’s official state news agency, Xinhua, warns that Falun Gong is incompatible with Marxism and that any party member who has faith in Falun Gong will “fall captive to idealistic heresies and finally lose credit as a communist.”

On September 23, 1999, Health Daily, the official newspaper of China’s Health Ministry, reported that prohibitions against Falun Gong had been partially extended to include Qigong in general. Under the new restrictions Qigong may not be practiced in government or military institutions, embassies, airports, train or bus stations, ports, streets, or other “important places.” Qigong schools are also banned. Qigong that is clearly “health enhancing” or “general” is allowed, but only in small, scattered, local, and voluntary groups. All Qigong groups must cease activities until they are registered with the government. The law is ambiguous enough that it may give license for party leaders to persecute Qigong practitioners whenever it suits their fancy. How does one distinguish the “important places” where Qigong is prohibited from unimportant places where Qigong is allowed? When does “health” or “general” Qigong become an unsanctioned form of spiritual cultivation? Who decides if a group is “small” and, thus, legal, or large and illegal? How does one define a Qigong school: fifty students practicing together, or a master guiding two apprentices?

Human rights groups are outraged by China’s crackdown on personal and religious freedom. Warren Allmand, president of the International Centre for Human Rights and Democratic Development, a Canadian human rights organization, expressed dismay at the way China has contravened international law “including the Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, which China recently signed . . . China is not only making a mockery of its international obligations but it also violates its own constitution . . . ” James Rubin, a spokesman for the U.S. State Department, objects to the “heavy-handed tactics being used to prevent Chinese from exercising internationally protected fundamental rights and freedoms, particularly the freedom of expression, association, conscience, and religion.” As late as February of this year, a Hong Kong-based rights group, the Information Center of Human Rights and Democratic Movement in China, reported that police had beaten to death a Falun Gong member and that the current repression campaign against the Falun Gong by Chinese leaders was the largest since their crushing of the pro-democracy protests of 1989.

Qigong is a comprehensive system of physical and spiritual cultivation from ancient China. It consists of postures, breathing techniques, exercises, and meditations designed to cultivate healing energy in the body (qi) and awareness of the energies of life around us. There are thousands of styles of Qigong, divided into several interconnected categories:

o It is the self-healing and wellness system of Chinese medicine (medical Qigong). oIt is a method of meditation (spiritual Qigong).

oIt conditions the body and improves performance in the martial arts and other sports (martial Qigong).

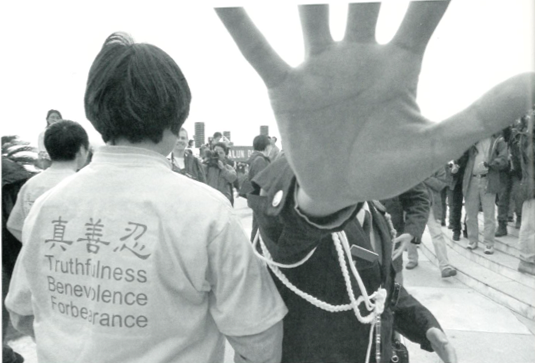

oQigong develops character (Confucian Qigong). To his credit, Li Hongzhi recommends the classical ethical dimension of Qigong. He advises his students to pay attention to XinXing (mental and spiritual nature) by cultivating Zhen-Shan-Ren (Truthfulness-Compassion-Forbearance). He tells his students to act selflessly, thinking of others before themselves and to obey the laws of their country. He eschews any political agenda or interests.

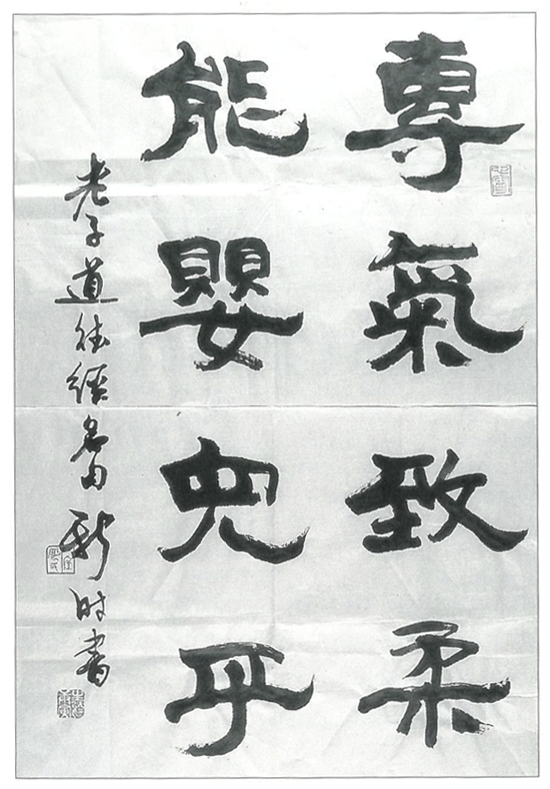

This is not the first time that Qigong or a particular method of Qigong has been prohibited in China. Qigong is rooted in Taoist and Buddhist philosophy, both of which-although not inherently political-have often inspired political activities or movements. Taoism and Buddhism are religious traditions that, while teaching practitioners methods of personal transformation, also teach ways to free oneself from cultural conditioning, particularly the conditioning influences of language and social roles. Lao Zi (fourth century B.C.E.), the founder of Taoism, tells us that if one can speak of Tao, it is not Zthe Tao, the mystical reality. Buddhism emphasizes freeing oneself of egotism and greed. Authoritarian governments often suspect that mysticism is threatening to their power and control. Buddhism, Taoism, and the arts they inspired (e.g., Qigong) seek truth through direct experience and thus encourage individualism, unpredictability, and perhaps a certain eccentricity.

From the beginning, Chinese Buddhists went against Confucian cultural norms. Monks owed their allegiance more to the sangha, their spiritual community, than to their biological families. Confucius said in the Analects, “While your parents are alive, do not wander far”-but monks are qu jia ren, “people who leave home.” Now we find a paradox: On the one hand, monks’ freedom from “the world’s dust” and their lack of political ambition gave them a reputation for being able to judge events impartially. Many emperors sought the guidance of learned Buddhist monks. On the other hand, the Buddhist emphasis on disattachment from society reminded the laity that it was possible to be free of political tyranny and, ultimately, to rebel against it.

Chinese rebels have often used-and sometimes twisted-Buddhist philosophy for their own purposes. Many have claimed to be Maitreya incarnate, a future Buddha waiting to be reborn to cleanse the world of wickedness. The earliest example of this occurred in 613 C.E. when a man named Song Zixian announced that he was Maitreya but was beheaded before his planned revolt. In 1047 an army officer named Wang Zi, another “incarnate Maitreya,” unified various rebel groups and occupied the city of Beizhou in Hebei Province. Eventually he was defeated by the armies of the Northern Song Dynasty.

The Song government banned Maitreya sects and other “heresies and unsanctioned religions.” Their followers went underground and merged into a new secret society, The White Lotus Society, which was involved in numerous revolts from the fourteenth through nineteenth centuries. (It is important to note that orthodox Buddhists did not support The White Lotus Society and regretted that its name was almost identical to the nonpolitical White Lotus Sect of devotional Pure Land Buddhism.) The imperial government was often extremely vicious in its attempt to root out these groups. During the late eighteenth century, more than 20,000 followers of White Lotus leader Liu Song were beheaded around the city of Wuchang during a four-month period. “Overthrow the Manchus, return to the Ming (Dynasty)” became the battle cry of the oppressed. The Buddhist Shaolin Monastery located on the central sacred peak of China (Mount Song) became a symbol of Chinese nationalism and the unification of the Middle Kingdom (Zhong Guo, China; in Chinese).

Taoism has an equally complex and turbulent political history. During the second century C.E., Zhang Daoling, charismatic leader of the newly formed Taoist Church, created a Taoist theocracy in western China. His soldiers were defeated by the armies of the Han Dynasty under General Cao Cao in 215 C.E. Like the Buddhists, Taoists expected a savior, a second coming of Lao Zi in his deified form as The Most High Lord Lao (Tai Shang Lao Zhun), also called Hou Sheng Dao Zhun (“The Sage Who Is To Come”). Sometimes Taoist groups rebelled against despots; sometimes, as in the Boxer Rebellion (1898-1900), against “foreign devils” who invaded their country from the outside. The Boxers were made “invulnerable” by Taoist ritual, shamanic spirit possession, and Qigong exercises. Unfortunately, they realized only too late that they could ward off magic bullets but not real ones.

Yet, through most of Chinese history and until very recently, Qigong techniques that were clearly part of Chinese medicineremained free of censure. During the 1950s Qigong healing and research centers were founded in several cities. However, with greater acceptance of healing Qigong, the spiritual side resurfaced-the healing and spiritual components, in my opinion, are inseparable. Qigong was again perceived by the government as part of Taoist and Buddhist cultivation. During the Cultural Revolution (1966-76), Qigong was officially prohibited, interest in it was discouraged, and practitioners went underground to avoid jail sentences.

In the early 1980s the ban was lifted, thanks to an endorsement by China’s leading scientist, Dr. Qian Xuesen, an MIT-trained nuclear physicist. Dr. Qian had determined that Qigong was a valid healing science that could lead to “a full development of man’s mental as well as physical abilities.” From 1982 to mid-1999, Qigong research and practice flowered. Medical Qigong was rigorously tested in scientific laboratories. Evidence suggested that it could be a powerful therapy for cancer, heart disease, chronic pain, and a host of other ills. China had reclaimed its great cultural treasure.

But the wheel of dharma turns, and Qigong has again become the underdog.

The question now is why has Falun Gong become so popular in modern China? I once asked a Westerner who had lived in China from 1936 to 1976 if she perceived any change in the character of Chinese people before and after the Communist Revolution. She said, “Yes, after the 1949 Revolution, people didn’t trust each other. You never knew if a remark would be reported to your party leader.” Friendship and true intimacy became difficult if not impossible. Psychological problems were redefined as political problems. According to Communism, maladjustment to an “ideal” political system requires political re-education, and so when people don’t trust-when they are disempowered and without access to spiritual guidance-they are more easily controlled by charismatic leaders and millennial philosophies. Falun Gong is filling a genuine need in Chinese society, a need for soul, a need for connection. Unfortunately, it is such a muddle of diverse beliefs that it is unlikely to accomplish the common goal of Taoism, Buddhism, and Qigong: clear awareness and enlightened wisdom.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.