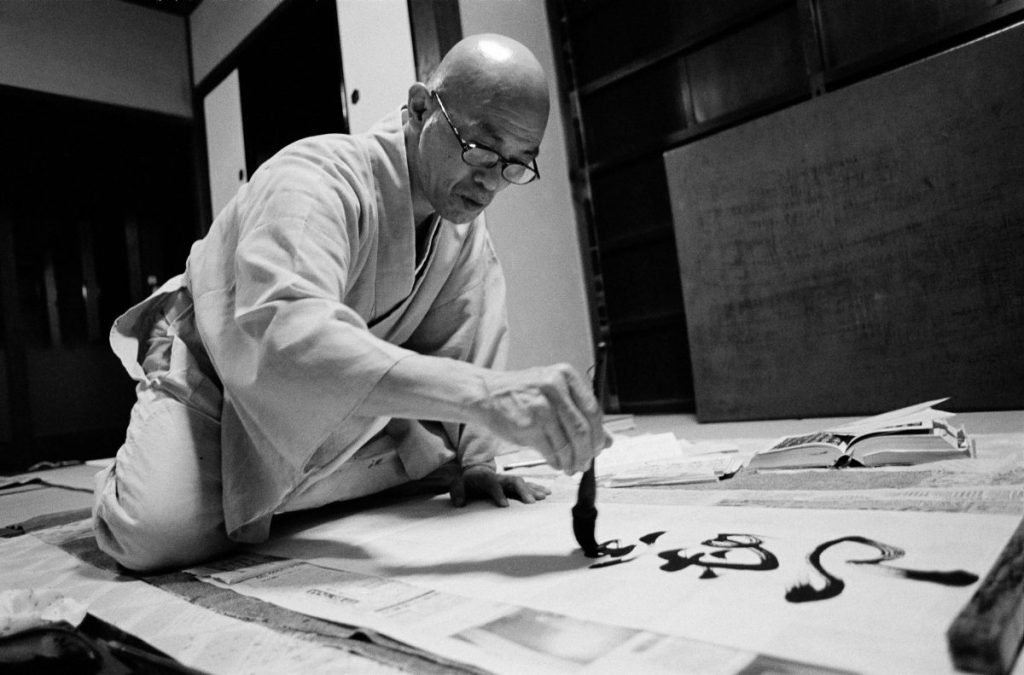

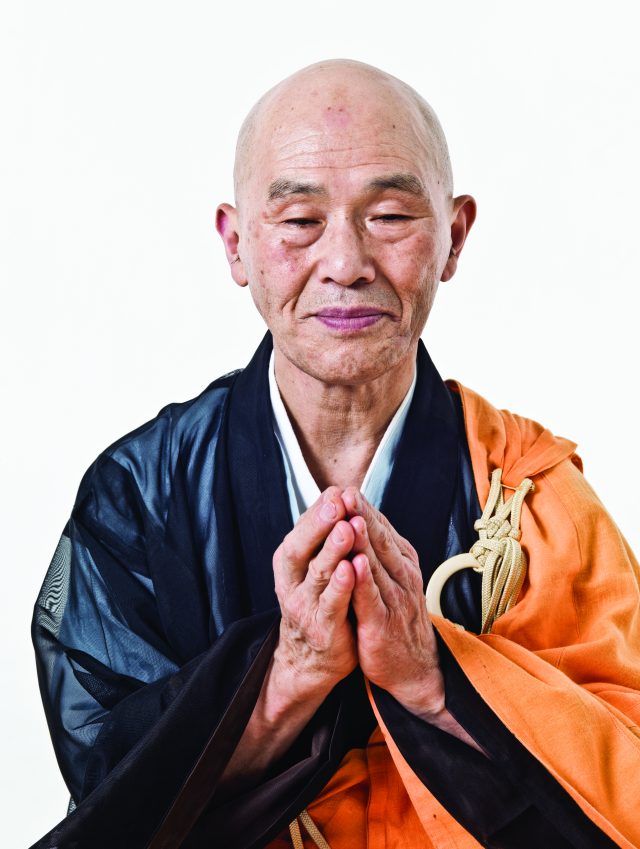

The following teaching is a commentary by the contemporary Japanese teacher Shodo Harada on the fourth chapter of the Platform Sutra. One of the most popular and influential texts of the Chinese Chan Buddhist tradition, the sutra is attributed to Fahai, a disciple of the Sixth Patriarch of Chan, Huineng (638–713 CE). Its ten chapters relate the patriarch’s talks.

One day, when addressing those gathered to hear him teach, the Sixth Patriarch focused on the nature of meditation and wisdom, explaining, “Meditation is the essence of wisdom, and wisdom is the function of meditation.”

Meditation and wisdom are not two separate things, as is stated clearly in the first two verses of the Dhammapada, a canonical collection of sayings attributed to the historical Buddha:

We are what we think, having become what we thought.

Like the wheel that follows the cart-pulling ox,

sorrow follows an evil thought.

We are what we think, having become what we thought.

Like the shadow that never leaves one,

happiness follows a pure thought.

zazen

(Chinese, zuochan), literally “seated meditation,” a basic practice followed by all schools of Zen (Chan). Here it is meant to be understood as letting go of preconceived ideas and remaining unmoved by external circumstances.

This is the essence of zazen, or meditation. Some people have many thoughts, and some have few. What we think about and hold on to affects what we perceive. When we hold on neither to thought nor to anything at all within, we perceive correctly with all our senses. Yet zazen and wisdom are not two separate things; we don’t do zazen and then become able to function wisely. Both our sitting and our actions are clarified when we let go of obstructive thinking.

samadhi

(Sanskrit, literally “placing together”); the meditative state of sustained one-pointed concentration; meditative absorption.

mu

(Japanese and Korean; Chinese, Wu), literally “without,” “nothing,” “not,” or emptiness; Mu is the first koan received in Zen practice in which the student works on becoming one with every action and situation of the day.

Wisdom comes forth only from clear, quiet mind. To hold on to nothing and not leave behind any remnant of thought is the mysterious nature of wisdom and the samadhi of meditation. Then everything we do is that samadhi, that Mu—eating, sleeping, standing, walking. But if we become attached to that practice, we again become trapped in our thoughts about it. Instead, leave no remnant of any thought behind, all day long! Even if you can do it in the zendo [meditation hall], if you are not able to keep it alive in your daily life, that is not true zazen. Zazen is not the form of sitting, but the practice of continually cutting away every extraneous mind moment. We cut as we see, as we hear, as we taste, as we smell, as we think, as we feel, and because we do this we are no longer pulled around by all that we see and hear and smell and taste and feel. But this does not mean that we don’t respond to things—we respond more sharply than ever, and more appropriately. If we are all falling asleep, feeling vague and fuzzy, we are not doing zazen correctly. It is a question of whether we are truly cutting and doing the practice thoroughly.

shikantaza

literally “just sitting,” the style of seated meditation practiced in Soto Zen. Rather than seek awakening by concentrating on a koan or following the breath, Soto Zen masters teach that one already possesses the awakened Buddha mind; by simply sitting in meditation, with nothing added, one manifests the awakened state.

Here the Sixth Patriarch is talking about the actual essence of the continuing, clear mind moments of shikantaza. Many claim to be doing a shikantaza practice, but this is an advanced practice that is difficult to do correctly. In shikantaza practice our mind, exactly as it is, is the Buddha. This is not just a technique; it is an actual realization of this state of mind. Following a technique is not the point. If what we realize in the zendo is useless outside the zendo, we will be unable to guide others. This is not about causing a physical change in the brain either. We have to use our brain fully, but without being moved around by things in any way whatsoever.

Although we talk about sudden awakening or gradual awakening, there is only one path. Even though everyone hears the same dharma [teaching], some realize it quickly and some take longer. This doesn’t mean that there are different dharmas, only that those who walk the path have different characteristics. The Sixth Patriarch was one who awakened suddenly, on merely hearing the words “abiding nowhere, awakened mind arises.” In that instant all his burdens fell away. But there are not many like this.

koan

Special words and experiences of the masters of old that are used to train our mind going beyond the intellectual abilities. In Zen training they are being used to help the student cut through their dualistic way of perception. They are given by a rosh [teacher] to the student, and are mulled over during zazen in an intuitive way.

Nonetheless, if we continue to be diligent, the more we realize, the deeper we go—until abiding nowhere, awakened mind arises. Just hearing these words, the Sixth Patriarch understood. We may hear and understand as well, yet in our daily lives still be subject to our habitual ways. And so we do zazen to cut all of this habitualization away. If we don’t cut, we end up carrying more and more burdens around. We have to use our koan or our susokkan practice as a sharp sword for cutting away everything! If we don’t actualize this, then we will have only an intellectual understanding of the words “abiding nowhere, awakened mind arises” and not be able to help others to awaken either.

susokkan

A breathing practice in Soto Zen meditation. One’s exhalations are counted with complete concentration and followed to the last point before inhalation, as ideas and memories arise and are allowed to pass.

Whether it takes 20 years to be realized or one instant, the awakened essence is the same for everyone. Even though this is what the Sixth Patriarch taught his students, his school in southern China became known as the Sudden Enlightenment School, while the teachings of Jinshu Joza (Chinese, Shenxiu) in northern China were called the Gradual Enlightenment School. This dichotomy reflects the poems the two wrote at the request of the Fifth Patriarch. Jinshu Joza’s poem says,

Our body is the bodhi tree,

And our mind a mirror bright.

Carefully we wipe them hour by hour,

And let no dust alight.

In response, the Sixth Patriarch wrote:

There is no bodhi tree,

Nor stand of a mirror bright.

Since all is void,

Where can the dust alight?

We are always thinking and confused, so Jinshu Joza said we should continually sweep our mind clean, but the Sixth Patriarch responded by saying that even thinking there is such a thing as a body and a mind is already extra—there is nothing from the origin, so why should we worry about dust alighting on it? These names sudden and gradual describe ability or perseverance, but in our buddhanature there are no differentiations such as earlier or later, first or last, sudden or gradual—that mind will not open completely if we hold to any such ideas!

buddhanature

The potential of all beings to attain buddhahood.

The Sixth Patriarch’s unique way of putting this is:

This teaching of ours has first taken nonthought as its central doctrine, the formless as its essence, and nonabiding as its fundamental. The formless is to transcend characteristics within the context of characteristics. Nonthought is to be without thought in the context of thoughts. Nonabiding is to consider in one’s fundamental nature that all worldly things are empty.

No one else has expressed the deep awakening of the Buddha and all of the patriarchs as well. We may believe otherpeople are good or bad, sick or healthy, but as long as we are concerned with our form or the form of others, we will be pulled around by our beliefs. In our true nature there are no such distinctions. This is Zen’s fundamental point. In our essence of mind, mountains are simply mountains, flowers are flowers, and the sound of the wind is the sound of the wind. We hear, we see, and we leave each thing as we hear or see it, adding nothing at all to it. Everything but that is just dualistic thinking. Changing with every single moment, our mind manifests our clear nature. This is “abiding nowhere, awakened mind arises.” In this way the Sixth Patriarch taught us.

We have a physical body, but our body is only a robe, and we will eventually have to take this robe off. Our body is not just moving around aimlessly, manipulating its arms and legs. Something is moving through it, something is wearing this body like a robe. Everyone takes the robe for what they are, but our true essence is not restricted by the design or form of this robe. In the words of Master Hakuin in his Song of Zazen: “Realizing the form of no form as form, whether going or returning we cannot be any place else. Realizing the thought of no thought as thought, whether singing or dancing we are the voice of the dharma.”

the platform sutra

The Platform Sutra (Chinese, Liuzu tan jing) is an account of the oral teachings given by the sixth (and last) Chan patriarch, Huineng (638–713), at Dafansi monastery in southeast China. The text is recognized as foundational in the development of East Asian Chan Buddhism and ultimately in the spread of Zen to the West. Its compilation is attributed to Huineng’s student, Fahai. One famous story related in the Platform Sutra is that of the context between Huineng and his rival, Shenxiu (see p. TK). Huineng was said to represent the Southern school’s “sudden teachings,” according to which enlightenment is a singular experience—a “re-cognition” of one’s innate enlightened nature; Shenxiu represented the Northern school’s “gradual teachings,” proposing that enlightenment is to be attained through a progressive overcoming of the distracted mind and its afflictions. While it was disputed whether or not the contest ever even happened, the account in the Platform Sutra of Huineng’s intellectual victory would give subsequent generations of Zen Buddhists, including those in the West today, an emphasis on the nonduality of enlightenment and a rejection of a linear path toward awakening.

As we go to the zendo or to do our work, we have to see how our mind actually functions. And so we carry our koan or our susokkan while working, sitting, eating, with no sense of doing any of these activities. With Mu as a sharp sword, while we eat, work, and sit, we are not moved around by the doing of that activity—a full, taut state of mind pours through us, manifesting as the activity. Not fuzzy and foggy but sharp and taut, we become the zendo. As we do in kinhin [walking meditation], we become the floor, with our whole body. With our whole being we work, we eat meals, and in this way we become that place of nonabiding. Not absorbed by objects when in contact with objects, we become one with whatever we do, becoming ever more transparent.

In our daily lives we are always carrying around self-conscious awareness. Being so familiar with that state of mind, we think it is normal and have to work at cutting it away. The more varieties of contact we have with the outside, the more we have to cut away. In this way Jinshu Joza’s lines “Our body is the bodhi tree, and our mind a mirror bright,” have relevance. And the Sixth Patriarch’s lines, “There is no bodhi tree, nor stand of a mirror bright,” tell us we cannot just conceptualize in that way and feel we have truly understood. We have to do it with our whole body; our practice has to be done with everything we are. As long as you are stuck in your head, your buddhanature will not be revealed. When you realize the actuality of each movement and can let go of all that differentiation, your breath naturally aligns. You come to know this place of “Realizing the form of no form as form, whether going or returning we cannot be any place else.” This is what the Sixth Patriarch is teaching.

In what way do we realize and awaken to the Buddha’s mind? Everything in nature has a physical body, yet a rock doesn’t call itself a rock or a flower call itself a flower. Only humans are stuck on how they are or should be. The healthiest way of being is to have no need to explain our being, but for it to manifest naturally. We get stuck because we feel a need to explain. We express many forms, but do we say when we are working, “Now I am working”? We don’t need such an explanation. While having a body, we must not get caught on the fact that we have a body. This is the essence of zazen: in everything to become what we are doing completely and totally. We live completely, and then we die completely. We don’t set our lives aside because of a fear of death; instead, we live wholeheartedly with every bit of our being. A dead person doesn’t say, “Now I am dead.”

Nonthought does not mean not to think; it means not to be carried away by any particular idea. We are humans, so of course we think; that’s what humans do. It has even been said that humans are legs that think. The purpose of Zen is not to become people who don’t think, but to think only what we need to; not to be lost in unnecessary thoughts, but to see what is most necessary right now. If we cook rice, we have to think about how much to cook and how to do it the best way. If we are chopping wood, we have to think about the best way to chop, or if we grow vegetables, we have to think about the best way to cultivate them. But people are always thinking instead about how they look to others. When it is cold, put on clothes; when you are hungry, just eat. No extra decorations need to be added to these actions. When you are sick, become sick completely. When meeting a crisis, instead of grumbling and saying, “Why did this have to happen to me?” just become that crisis completely, without separating from it and complaining. Don’t think about extra things, but live totally embracing just what comes to you, not carrying thoughts about the past or wondering what’s going to happen in the future. If you only think what is necessary, you won’t be carrying the past around, thinking, “I should have done that,” “Oh, if I’d only done it this way.” We miss the present when we carry around these kinds of thoughts. Live this moment fully in the most appropriate way!

the sixth patriarch huineng

Huineng was born to a poor family in present-day Guandong province of southeast China. The stories of his life are many and varied, but according to the Platform Sutra, he joined a monastery as a young man after hearing someone recite the Vajracchedikaprajnaparamita Sutra (Diamond Sutra) in the marketplace and becoming enlightened on the spot. He received transmission in secret (along with the robe and bowl of Bodhidharma, the founder of Chan) from Hongren, the fifth patriarch of Chan, but went into hiding to avoid pursuit by followers of his rival Shenxiu; after some years he emerged to teach at Baolin temple on Caoxishan, a mountain in northeastern China.

Nonabiding or nonattachment is the characteristic of our essence of mind. With nonattachment we have no time to get caught on things; we are always flowing. When we stop flowing, our mind becomes foul like stagnant water or fixed like water frozen into ice. If we are distracted by extraneous thinking while doing zazen, it is not dangerous. But if we are driving a car and get lost in our extraneous thoughts, it is dangerous. The nonabiding mind of zazen is not just for being in the zendo. Whether we are sitting, moving, working, silent, or speaking, all of it is zazen. The cultivation of flowing mind is zazen. Then we can become the flower, become the moon, become the stars—absorbed into them, we become everything we encounter completely and totally. That is our correct state of mind.

♦

From Not One Single Thing: A Commentary on the Platform Sutra, by Shodo Harada © 2018. Reprinted with permission of Wisdom Publications.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.