By some estimates, there may now be three million or more people in the United States who identify themselves as Tibetan Buddhists. Sixty years ago, there were precisely 587 of us who could assert that claim—and we were all Kalmyk Mongols.

Eighteen years before Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche—the charismatic tulku widely assumed to have brought Tibetan Buddhism to North America—set foot in the States, a small band of Kalmyks, America’s earliest Tibetan Buddhists, would establish the religion’s first temple in the Western hemisphere. Refugees from Stalinism and unlikely beneficiaries of America’s early Cold War maneuverings, the Kalmyks transformed an unassuming town in the middle of New Jersey into the epicenter for Tibetan Buddhism in the West.

The community’s most learned lama, Geshe Ngawang Wangyal, was the first Tibetan Buddhist lama in the United States to take on American students. His long list of accomplishments would include pioneering efforts in establishing Tibetan Buddhism’s intellectual bona fides in American academia and popular culture, making possible the successful escape of His Holiness the Dalai Lama from Tibet in 1959 under contract with the CIA, and finally, spearheading a two-decade-long undertaking to remove political proscriptions on American visits by the Dalai Lama, an endeavor that reached up to the highest levels of US government. Not many Western Buddhists know this story—or that the tradition’s first congregation here would have such an improbable yet discernable and documentable impact on Tibetan Buddhism’s future in America.

In the summer of 1952, Jersey Shore–bound travelers zipping down US Route 9 would not have noticed anything that set Freewood Acres, New Jersey, apart from thousands of similar villages throughout America. Nothing on its public face suggested that Freewood Acres had, over the previous winter, become a demographically singular community on this side of the world. The distinction was due, in part, to the decision by a band of about 200 Kalmyks to resettle there permanently (amid an already established Cossack community) shortly after their 1951 Christmas Eve arrival in America. These Kalmyks had avoided all but certain extinction because of their propaganda value in a spirited battle for global domination being waged by their once and current sovereigns.

The emigrants—nearly half of whom, myself included, were children under the age of 10—landed with only the tattered mementos of six joyless years in a series of Bavarian Displaced Persons (DP) camps cobbled together by the US Allied Forces in Germany to accommodate a portion of the millions uprooted by the Second World War. Each could trace his or her immediate origins to the Russian steppes northwest of the Caspian Sea, to a land they fondly called Hal’mag Tangach’, dubbed “Kalmykia” by their Russian and Cossack neighbors, from a word of Turkic origin meaning “to remain.” The Kalmyks had done just that after emigrating from western Mongolia to the Volga Basin in the early 17th century, establishing the only Buddhist polity in Europe at around the time the Puritans landed at Plymouth Rock.

Most of Freewood Acres’s Kalmyk adults had fought or worked for the Third Reich following the Nazi’s massive attack and subsequent occupation of their Russian Soviet Republic in the spring and summer of 1942. Spurred by the woes of Stalinist oppression, some became “guest workers”; the rest bore arms against the USSR, either as part of the doomed Russian Liberation Army or as members of the so-called Kalmyk Cavalry Corps, created by the German Wehrmacht during its Sixth Army’s brief occupation of Kalmykia as it mustered for the coming disaster in nearby Stalingrad. Understandably, no Kalmyks acknowledged this toxic allegiance in the wake of Germany’s defeat, and at war’s end each would profess involuntary servitude as the reason for his presence in Germany, usually under an assumed name.

Perhaps that was why we were among the very last of Europe’s DPs, still homeless and stateless six years after the end to hostilities. Desperate to preserve a unique cultural heritage in the midst of a physically devastated and morally depleted Germany, Kalmyk DPs rejected opportunities for individual or family resettlement, knowing that any attempt to break them up was tantamount to a death sentence for our culture and survival as a distinct people. Furthermore, in contrast to other past DPs, we were undeniably Asian, physically and culturally. Surprisingly urbane and broadly polyglot on the one hand, Kalmyk Mongols also unabashedly embraced and celebrated religious beliefs and core values found only in more exotic locales and distant times. For a mostly Christian Europe, this feature may have fostered a perception that Kalmyks were little more than godless primitives, perhaps not so far removed from our “barbarian” forebears. Little wonder, then, that there were few offers of safe haven from the community of nations.

In the immediate aftermath of Germany’s defeat, millions of their former countrymen and women—Cossacks, Soviet POWs, German collaborators, and other anti-Stalinists—were forcibly repatriated to Russia by its US and UK allies. Like most of those forcibly returned, Kalmyks harbored a visceral hatred of Communism and Stalin, nurtured in their beleaguered homeland and in European exile. In the early years of the Cold War, this particular stance, and the conviction with which Kalmyks held it, perhaps trumped the negative factors hindering our search for a permanent communal home. Impeccable anti-Communist credentials coupled with a history of persecution in the Soviet Union tipped the balance in our favor when the United States relented and offered Kalmyk Mongols permanent refuge. Our flight from Communist tyranny and eventual “redemption by the West” was valuable propaganda fodder for the political era that followed Mao’s revolution in China, witnessed an alarming upsurge in Communist-led national liberation movements in Southeast Asia, and saw the grisly escalation of hostilities on the Korean peninsula. Virulent anti-Communist Asians, it seems, were at a premium.

At first, the passage and enactment of the DP Act of 1948, a humanitarian measure to grant permanent US residence to 200,000 refugees still languishing in European DP camps, did not affect the Kalmyks’ eligibility, because its benefits applied only to white people. It was only with the help of Leo Tolstoy’s youngest daughter, Alexandra, one of perhaps a half-dozen Americans who even knew what a Kalmyk was, that we were granted asylum. Through her foundation, Tolstoy posited before an immigration tribunal that the Kalmyks’ centuries-old inhabitation of their own polity within European Russia far outweighed their actual and obvious Asiatic origin. In other words, Kalmyks were really Europeans. Despite the initial tribunal’s rejection of this argument, its appellate superiors, the Board of Immigration Appeals and the US Attorney General, reversed the decision months later, making the European Kalmyks beneficiaries of an innovative legal ruling exempting us from the anti-Asian (“Yellow Peril”) hysteria that had swept America and found purchase in its immigration laws.

By figuratively sticking her foot in America’s front door and keeping it wedged there long enough for an anonymous band of war-tossed Mongols to navigate around daunting racial barriers, Countess Tolstoy not only became the architect of the Mongol “invasion” of New Jersey and the country’s first ethnic Mongolian community, she also served as the midwife for the birth of Tibetan Buddhism in America.

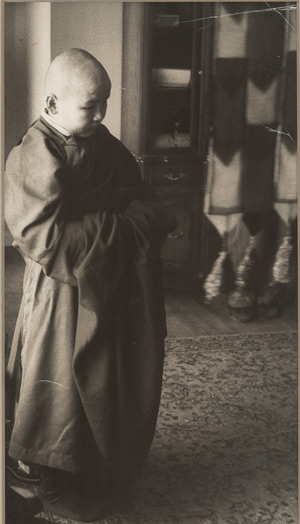

One month short of the first anniversary of their arrival in America, the Kalmyks of Freewood Acres consecrated a communal worship center, their main priority since leaving the camps. The extensively renovated garage, once ritually transformed, symbolized the Kalmyks’ determination to bring their long, arduous journey to an end. The two modest bungalows that shared the site with the transformed garage became housing for the sangha of a half-dozen monks and lamas who had followed their parishioners out of Russia. They gave their new temple a traditional Tibetan name, Rashi Gempil Ling, hoping that it would indeed be a “Sanctuary for the Increase of Auspiciousness and Virtue.” That it was the first Tibetan Buddhist worship center established in the Western hemisphere probably was not foremost in anyone’s mind.

Coverage of the sanctifying rite in The New York Times betrayed the Cold War mentality typically found in the era’s news stories about recent refugees, fixing as it did on the group’s collective plight in recent years and its eventual deliverance from Soviet Communism by the US. The Siberian exile of the Kalmyks’ unfortunate compatriots in Russia was also mentioned, perhaps as an example of what these lucky ones had avoided through America’s compassionate intervention.

The brief article was the most prominent press attention Kalmyk DPs had received to date. And because it was published in the paper of record, it was the most widely disseminated account of the circumstances of our arrival the previous year. Beyond the hundreds of thousands of Times readers and subscribers learning for the first time that there were now “descendants of Genghis Khan” in their midst, the story’s reverberations eventually reached halfway around the globe to the West Bengal town of Kalimpong, India. There its message resonated with a fellow Kalmyk Mongolian who had been living in exile in the former hill station of the British Raj since shortly after the 1950 invasion of Tibet by China. Geshe Ngawang Wangyal’s curiosity was piqued.

The Kalmyk Autonomous Oblast in the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic had barely celebrated its second anniversary in 1923 when 21-year-old Lidjiin Keerab, a Buddhist seminarian, left his home in the Lesser Derbet region to complete his ecclesiastical education in Tibet. He was one in a small but continuous trickle, beginning in the mid-to-late 1600s, of Kalmyk geshe-aspirants making the trek. He and his predecessors intended to eventually return home to disseminate buddhadharma among the Kalmyks, the world’s westernmost Buddhists. Keerab, who would complete his studies to become Geshe Wangyal, did not know that he would be the last Kalmyk to make that passage.

Keerab had been a gifted student in one of Kalmykia’s two monastic colleges (chöra) founded two decades earlier by his guru and patron Lama Agvan Dorjiev, a Buryat Mongol geshe from Siberia and an ecclesiastic tutor and debate partner to the 13th Dalai Lama. Although dragged into the geopolitical feuds of the time, Lama Dorjiev spent most of his life promoting the academic study of Buddhism in Mongolia, Buryatia, and Kalmykia according to a curriculum established by the Tibetan monk and scholar Lobsang Drakpa, better known as Tsongkhapa, the 15th-century founder of the Tibetan Gelug lineage.

Recognizing his protégé’s potential to successfully complete the demanding geshe curriculum at the Gelugpa monastic colleges of Tibet, Dorjiev handpicked the young Lidjiin Keerab to be a member of the Borisov Mission, a secret undertaking hatched by the USSR’s foreign ministry and Comintern functionaries. The expedition’s leader, Sergei Borisov, and his travel companions would pose as religious pilgrims while actually exploring opportunities for Communist proselytizing on the “roof of the world,” which conveniently overlooked colonial India, the crown jewel of Britain’s massive empire. Comrade Borisov, a seasoned Comintern operative of Central Asian descent, donned the robes and persona of a Buryat Mongol lama for the months-long trek to Lhasa. To add further credibility to the ruse, Borisov brought several genuine Russian Buddhist pilgrims into the party, including Lama Dorjiev’s promising disciple.

Knowing well the ulterior political motives of the caravan’s sponsors, Lama Dorjiev admonished Keerab to separate from the caravan before its entry into the holy city and to avoid being identified thereafter as a member of Borisov’s party. Borisov’s group would be the last sanctioned overland expedition from Russia to Tibet, ending a centuries-old practice by which Kalmyk traders, monk-students, and pilgrims could stockpile incalculable merit from completing the holy circuit.

Keerab completed his curricular obligations at Gomang Monastic College’s geshe-degree program in less than ten years, about half the time for typical geshe-aspirants. In 1933 or early ’34, Geshe Wangyal made his first (and last) attempt to return to Kalmykia, an endeavor cut short by the ongoing suppression of Buddhism along his proposed return route in Mongolia and even more vigorously at his intended destination. Stranded in Beijing, Geshe-la took a job with a Chinese publishing venture attempting to reconcile various versions of the Buddhist canon, taught school briefly in Inner Mongolia, and, presciently, began teaching himself English.

Following a quick visit to England at the invitation of the author and mountaineer Marco Pallis, Geshe Wangyal returned to Tibet, resolving to spend the rest of his life there. For more than a decade, Geshe-la would spend most of the year in Lhasa and winter in Kalimpong, India, allowing him to conduct lucrative trade between the two countries and sometimes with China. It was a near-idyllic existence.

Late in 1950, however, the first Chinese Communist artillery shells fell on Eastern Tibet, ending the optimistic notion that Tibet could maintain its historical independence. The Asian expansion of Communism and the consequent devastation of Buddhism that Geshe-la had witnessed over the past three decades had finally caught up with him in Tibet, his most secure redoubt. He could not hope to remain in Lhasa, where his identity as a Russian subject was quite well known and his status as a lama and trader made him an obvious target for the coming wave of ideologues charged with purifying society of its bourgeois elements.

By the end of 1951, as Chinese propaganda cadres and armed forces expanded their presence into Central Tibet from the eastern provinces, Geshe Wangyal had permanently relocated to his winter refuge in India. Soon after, the jungle drums communication network of Kalimpong’s sizeable Tibetan exile community informed him that, according to an article inThe New York Times, a group of his fellow Kalmyks had established a small community and congregation in a place called New Jersey.

For a full year thereafter, Geshe-la made multiple requests to the American Consul in New Delhi for a visa. It was eventually granted in late 1954 after the intervention of the Tolstoy Foundation a year earlier. With all his earthly possessions packed into two steamer trunks, Geshe-la made his way to France in time to catch La Liberté’s January 1955 departure for the port of New York. He would spend the next 28 years in New Jersey, the longest continuous residence in one place in his eventful life, making him, in a very real way, the first authentic American lama.

Following his arrival, Geshe Wangyal attempted to join the sanghas of the Kalmyks’ original temple organization, Rashi Gempil Ling, as well as the newest one, Tashi Lhunpo, built on a large communal plot in the adjacent Howell Township. He had been rebuffed by each primarily because of the interventions of Dilowa Khutuktu, a Mongolian-born tulku who had been in America since 1949. The resulting acrimony in the community between Geshe-la’s defenders and detractors exposed fault lines along tribal and clan affiliations that had always been part of the Kalmyks’ group and individual identities.

Membership in either temple organization would have spared Geshe-la the necessity of raising the funds required to purchase property and build the facility he would need to house the modest Buddhist Studies and Tibetan Language program he hoped to start as a faint echo of the academies established in Kalmykia by his own guru, Lama Dorjiev. However, Geshe-la’s initial urgency to be accepted within the existing Kalmyk organizations appreciably diminished around the time he began his contract work for the CIA, in 1956 or early 1957. Recruited to the spy agency with the help of the Dalai Lama’s eldest brother, Thubten Jigme Norbu (Takster Rinpoche), Geshe Wangyal developed the Tibetan telecode the agency would use to communicate with the Tibetan Resistance, the newest surrogates for fighting communist expansion.

Takster Rinpoche emigrated to the United States under CIA sponsorship eight months to the day following Geshe-la’s arrival in New Jersey. His initial visit in 1951, referred to in some news accounts as a lecture tour of seminaries and colleges, was arranged by a CIA-front organization and used to present his own eyewitness accounts of the Chinese invasion and occupation of Tibet at very high levels of America’s foreign policy and intelligence communities. During his second visit, Rinpoche’s friend and colleague Geshe Wangyal served as his translator for the interview at the offices of Rinpoche’s US sponsor. The two had last seen each other in Lhasa 16 years earlier.

The Agency’s choice for its code designer was, according to Kenneth Conboy and James Morrison in The CIA’s Secret War in Tibet, a given, since Geshe Wangyal was “the first (and at that time, only) qualified scholar of Tibetan … in the United States” who could develop the code and then train the Tibetan warriors (some of whom were only nominally literate) in its use. In other words, there was no one else in America who could have done it.

Geshe-la’s mandate within the task force also consisted of deciphering and encoding all messages between the Agency and the guerrilla forces for an extended period. Geshe-la, Takster Rinpoche, and the CIA spooks trained the first group of Tibetan guerrillas in the code and tradecraft for its use on the island of Saipan in the western Pacific in 1957. Later, the majority of CIA-trained nationalist forces would receive that training at Camp Hale, a decommissioned WWII– and Korean War–era army base in the Rocky Mountains outside of Leadville, Colorado. These Tibetans, after completing their training by the CIA, would be airdropped back into Tibet to gather intelligence and relay their information to Washington. They were also trained to recruit more resistance members and to conduct opportunistic sabotage.

The material rewards from Geshe Wangyal’s involvement with the US government became evident when he commissioned the construction of a nondescript, ranch-style home on East Third Street in Freewood Acres. Aside from the deer-and-dharma-wheel emblem (hand-carved by Geshe-la) displayed atop the portico of its front door, there was nothing about the typically suburban structure to indicate that it was America’s first center for the academic study of Tibetan Buddhism. The name on the corresponding mailbox at the edge of the street read Lamaist Buddhist Monastery of America (LBMA). From that point on, Geshe Wangyal would proceed according to his own agenda, which took a decisive turn in the year His Holiness the Dalai Lama escaped to India, a feat in which Geshe Wangyal played no small part.

The combined efforts of Geshe Wangyal and Takster Rinpoche at the birth of the organized Tibetan resistance made it possible for ST Circus, the CIA’s codename for its anti-Chinese effort, to achieve its most notable success: the Dalai Lama’s escape from Tibet. Fortuitous contact by members of the first class of US-trained Tibetan resistance fighters with the Dalai Lama’s escape party in March 1959 allowed the CIA to be informed daily of the Dalai Lama’s whereabouts throughout the grueling ordeal. At the time, 50,000 People’s Liberation Army soldiers and dozens of spotter planes scoured the Tibetan side of the Himalayas trying to thwart his escape—or, as they suggested, to rescue him from kidnappers.

Besides keeping their CIA patrons updated on the escape party’s coordinates, the guerrillas used Geshe-la’s telecode to request from Prime Minister Nehru’s government political asylum in India for the Dalai Lama, his cabinet, and his family. Three years earlier, Nehru had turned away a similar request and essentially forced His Holiness to return to Tibet after a brief religious pilgrimage to India. It was thus a great relief when Nehru’s consent to the asylum request, after traveling through several bureaucratic levels of the US and Indian governments over a 24-hour period, was relayed to the Dalai Lama’s Lord Chamberlain by the CIA-trained guerrillas. That message permitted a then ailing Dalai Lama to cross into Indian refuge ahead of his pursuers.

His Holiness’s decision to leave Tibet at that time, almost nine years into China’s occupation, and the details of how and whether he was eluding the Chinese army became fodder for international journalistic speculation as hundreds of newsmen flocked to India’s remote Himalayan outposts hoping to witness his arrival. Few can remember today that this was the most internationally covered cliffhanger of that era, one that resonated well in the existential drama of the ongoing Cold War.

Once His Holiness the Dalai Lama was safely in India, Geshe Wangyal would soon discover that the follow-up task of bringing His Holiness to the United States might be more daunting than the just-concluded escape. For that project, he would need other allies—and plenty of patience.

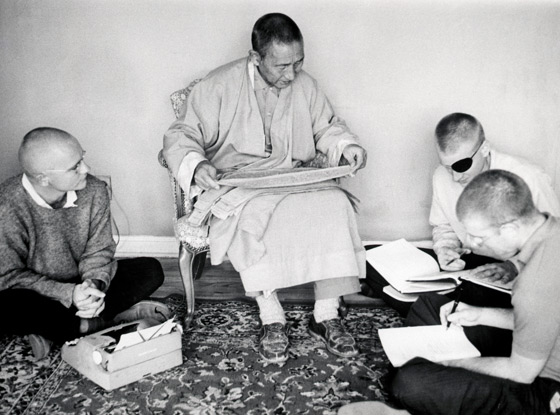

In 1960, Geshe-la quit the CIA assignment. (The CIA’s Tibet program continued for more than a decade without him, until it was ended by order of Henry Kissinger when he began his courtship of Mao in the early 1970s.) As this was also his first year of eligibility, Geshe Wangyal petitioned for and received United States citizenship and an American passport. He used the latter to return that summer to India, where he met with the Dalai Lama, then into his second year of exile. Although Geshe-la, to my knowledge, never spoke openly of his private conversations with His Holiness—just as he never mentioned his involvement with the CIA’s Tibet Task Force—the results of their initial meetings became apparent in 1962 when His Holiness sent four Tibetan lamas from India to Geshe Wangyal’s center in Freewood Acres, primarily to learn English. The group included Geshe Lhundup Sopa, later a decades-long professor of Buddhism at the University of Wisconsin; Lama Kunga Thartse Rinpoche, founder of the Ewam Choden Buddhist center in California; and two teenage tulkus, Kamlung and Sharpa Rinpoches. The steady procession of Tibetan lamas to LBMA under this informal program continued for an additional ten years. Eventually the lamas’ mandate to learn English was expanded to include teaching Buddhism to receptive audiences. Many alumni of the program, like Geshe Sopa and Lama Kunga, would go on to establish their own active American dharma centers, which attracted hundreds of devoted followers and disciples. One of the last to arrive under this arrangement, Geshe Lobsang Tharchin, became the longest-serving abbot of the Kalmyk community’s Rashi Gempil Ling temple.

Shortly after the arrival of that first group of “ESL-lamas,” LBMA took in its first resident students when a trio of former Ivy Leaguers—Christopher George, Jeffrey Hopkins, and Robert Thurman—who, as The New York Times wrote, could “trace their American descent to the early days of the Republic,” came to begin study in Buddhism and Tibetan. In return for their studies with Geshe Wangyal and the new lamas, the Americans provided English language lessons for the newcomers and manpower for the addition of an altar room and dormitory, which Geshe-la ordered to accommodate LBMA’s sudden population explosion. The bargain struck between scions of America’s oldest settlers with members of its newest furthered the future expansion of Tibetan Buddhism in the West for decades to come, primarily from the efforts of two of these pioneers, Robert Thurman and Jeffrey Hopkins.

Dr. Thurman’s academic career and record of activism on and education about Tibetan spiritual, cultural, historical, and political issues in the past half-century is well documented, as are Professor Hopkins’s contributions to the academic study of Buddhism since his apprenticeship at LBMA. Teaching at Columbia University and the University of Virginia, respectively, together they form two pillars upon which much of Tibetan Buddhist studies in America rest today. These two trailblazers contributed to the emergence of a second generation of scholars, teachers, and activists who made their own unique contributions to the remarkable growth of interest in and understanding of Tibetan Buddhist doctrine in America.

In 1964, Geshe Wangyal traveled to India, taking Thurman along. He introduced him to the Dalai Lama, who had just moved to the hill town of Dharamsala. There, Thurman served a brief tenure as a Tibetan Buddhist monk—the first American to do so, and the first Westerner to be ordained by the Dalai Lama—before returning to America later in the 1960s and reentering Harvard University to earn his PhD in Buddhist Studies. While at Harvard, Thurman befriended two undergraduates, Joel McCleary and Joshua Cutler, who had been taking introductory Tibetan Buddhism classes with him. Both expressed a keen interest in continuing those studies after their upcoming graduation. Naturally, Thurman referred them to his own lama.

More than 40 years later, McCleary still remembers the first task Geshe-la assigned him after he and Cutler arrived at the LBMA retreat house in the summer of 1971: Bring the Dalai Lama to America. Geshe-la’s decade of experience with bringing Tibetan lamas from India had been both rewarding and extremely frustrating. True, there were more Tibetan (and even Mongolian) lamas and geshes in the United States than at any other time. Yet seemingly intractable obstacles, mostly of a political nature, had thus far blocked any hope that the Dalai Lama would someday be able to join them. As early as December of 1959, President Eisenhower, on a state visit to India, refused to meet with His Holiness despite clear overtures from the Tibetan side requesting a meeting. That semi-public snub established the official policy of the United States toward the Dalai Lama for the next 20 years: His Holiness was persona non grata despite the absence of any formal announcement of such status.

At the time, much of America’s foreign policy regarding Asian issues was determined by supporters of Chiang Kai-shek and his Kuomintang regime’s claim to be the real government of China, even after its forces were driven out of power and into Taiwanese exile by Mao Zedong’s minions. This influential group was called the China Lobby, and their claims to ownership of Tibet mirrored the ones put forth by their political rivals. That the Dalai Lama’s Government-in-Exile was then promoting Tibet’s de facto independence since 1911 insured that neither Chinese faction would look favorably on any official contact between the United States and His Holiness, and that each, indeed, would do all it could to thwart it.

McCleary’s one-man letter-writing campaign to Congressional leaders, begun in response to Geshe-la’s request, took a substantial turn for the better when he became Deputy Assistant to the President for Political Liaison in the Carter Administration at the end of 1977. (McCleary’s path to the West Wing and eventful career as an international political consultant after leaving LBMA are explained in his essay “Confessions of a Buddhist Political Junkie,” published in Tricycle’s inaugural issue in the fall of 1991.)

Tom Beard, a fellow Deputy Assistant to President Carter at the time and a charter member of his team of outsiders known as the Georgia Mafia, freely admits that his own enthusiastic involvement in upending the State Department’s policy was based solely on McCleary’s compelling arguments in favor of its reversal. Many staunch supporters of the policy, with whom McCleary and Beard tussled, would later become the Dalai Lama’s best friends in America. Once Beard was on board, the two Deputy Assistants, with silent but solid backing from their colleagues in the White House, finally forced the issue of a Dalai Lama visit to vigorous debate at the highest levels of government, something no previous administration had dared to raise. What began as a series of calls to the American Embassy in New Delhi, announced by the intimidating words, The White House is calling, and asking the startled diplomats if they had read President Carter’s policy on human rights, soon became an agenda item before the National Security Council. There the debate would be joined by proponents of the visit, including Hopkins, Thurman, Tenzin N. Tethong (from the Office of Tibet in New York City), Beard, and McCleary, who presented it as a logical extension of President Carter’s commitment to human rights, the hallmark of his foreign policy following the “normalization” of relations with the People’s Republic of China shortly after taking office.

The important point here is not that the Tibetophiles won the debate, but rather that it took place at all. In retrospect, it is hard to imagine a similar scenario taking place in succeeding administrations, whose China policies and sensitivities were identical to those of the ones preceding President Carter’s and whose interest in human rights issues were demonstrably not as keen. If Joel McCleary had not been at the White House at that instant in history, it is doubtful that His Holiness could have come to America when he did—or come at all.

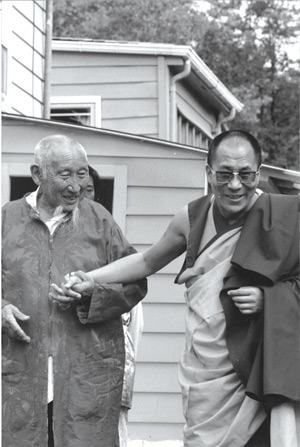

The Dalai Lama made his American debut in September 1979, beginning a seven-week, nationwide teaching tour from the campus of the Lamaist Buddhist Monastery of America in New Jersey. The first private audience His Holiness gave at LBMA on the morning of his first teaching in America was with Joel and April McCleary (and a very surprised yours truly). His Holiness’s maiden visit demolished any chance of reimposing the unspoken ban on US visits by the Dalai Lama. Instead, it marked the start of America’s—and the world’s—love affair with the “simple Buddhist monk.”

The Dalai Lama has returned to LBMA, renamed the Tibetan Buddhist Learning Center (TBLC) in 1984, a total of eight times since his first visit. The most recent came in 2008 when he delivered a six-day teaching, held at nearby Lehigh University, on Tsongkhapa’s The Great Treatise on the Stages of the Path to Enlightenment in appreciation of TBLC’s completion of the English translation of the three-volume magnum opus. The 12-year, multi-translator project had been overseen by Joshua Cutler, who first came to Geshe Wangyal’s center in 1970 with McCleary and stayed long enough to become Geshe-la’s principal disciple. Cutler and his wife Diana would become successors to their lama as TBLC’s Executive Directors upon Geshe Wangyal’s death in 1983.

On the first day of His Holiness’s marathon event, he recalled what proved to be his final meeting in 1981 with his old friend and colleague, “Wangyal-la.” Geshe-la had convened all of his disciples and closest friends in the library of the LBMA’s schoolhouse in preparation for a communal farewell to His Holiness after he concluded his second teaching visit to LBMA. When His Holiness entered and joined Geshe-la at the front of the room, Geshe Wangyal burst into uncontrollable tears even as His Holiness hugged him closely and playfully tugged at the whiskers of his long white goatee. Finally, His Holiness also succumbed to the poignancy of the moment and began weeping for reasons we all knew could never adequately be expressed with words. It was the most moving spiritual moment I have ever experienced; His Holiness thinks of it too whenever he recalls Geshe Wangyal.

The final piece of the narrative, for me, fell into place in southeastern Russia in the summer of 1991, a dozen years after His Holiness’s American debut. I was extremely privileged then to accompany the Dalai Lama on his first pastoral visit to Kalmykia. As His Holiness the Dalai Lama disembarked into a throng of jubilant Kalmyks waiting on the airport tarmac, someone cried out, “Your Holiness, why are you here?” Without hesitation, the Dalai Lama responded, “I’m here because of my friend Geshe Wangyal.”

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.