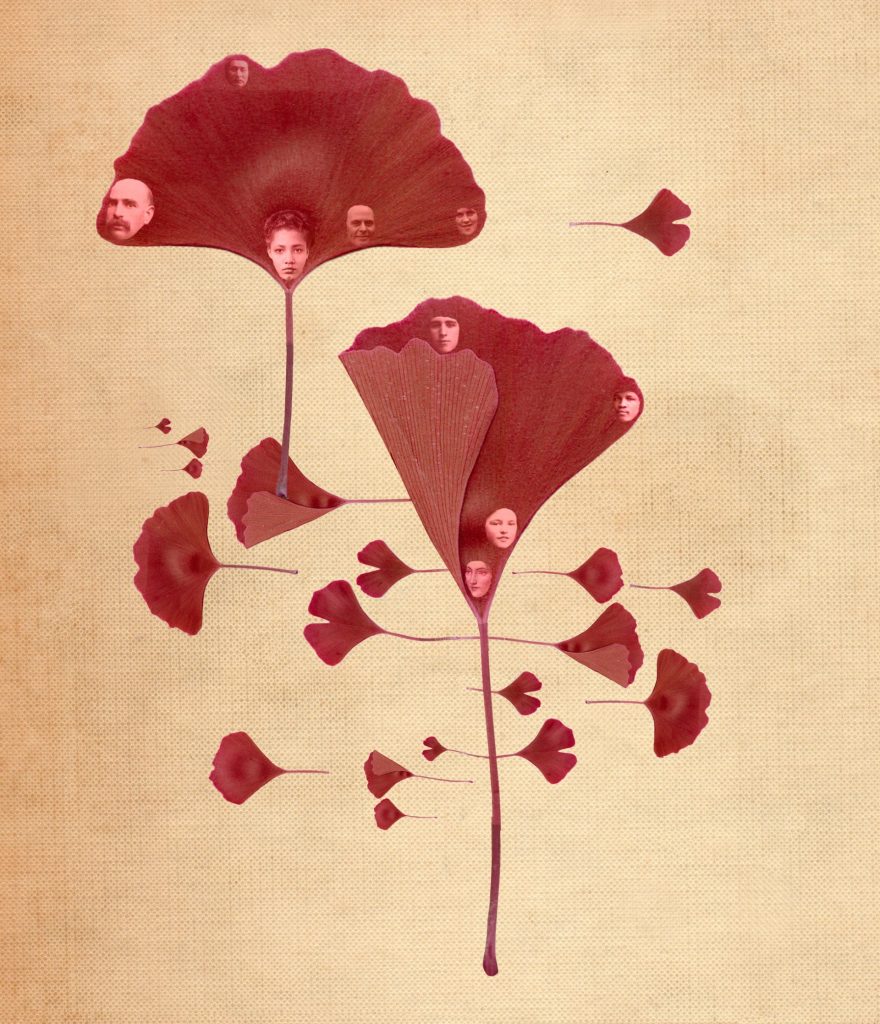

my elders slowly

becoming my ancestors—

red leaves in the wind

–Valerie Rosenfeld

The poet Basho once remarked, “What is the use of saying everything?” As contemporary haiku master Mayuzumi Madoka explains: “It is between the lines—in the words that have been left unsaid—that the haiku communicates the poet’s deepest sentiments and thoughts. Words alone cannot describe the fullness of the human experience.”

“My elders are slowly becoming my ancestors,” confesses the poet in her Fall 2025 Best of Season haiku. She then pivots to the image of “red leaves in the wind.” She holds back from asserting a relationship between the two parts of the poem. Their meaning lives in that unspoken connection.

In haiku poetry, red leaves are associated with that noticeable quickening we feel as the year begins to draw toward its close. Thus, the final image accelerates our experience of time. The poem invites a metaphorical comparison between the leaves and the elders, but there is a difference. The latter have entered the timeless realm of the ancestors, while the leaves are falling now: right before our eyes.

From its earliest origins, haiku was a collaborative form of literature that relied upon an imaginative exchange between poet and reader. The poet’s job was to establish a range of possible meanings that would allow the reader to intuit the substance of the poem. With that in mind, on first reading most of us will find ourselves standing outside on a late autumn day as the wind snatches a few crimson leaves from trees. But something curious happens when we read the poem again, touching back on the beginning to grasp the moment whole.

Basho described the little flash of cognition we experience in a good haiku as the movement of “the mind that goes out and returns.” Having ventured briefly into the shared space of the poet’s reality, the pendulum swings back to the reader to complete the poem. That is where the meaning happens. It lives in the reader and not on the screen or the page.

The word “slowly” suggests a series of significant losses in recent years. Something about the red leaves falling all around her triggers the poet’s realization that there are still more losses to come. They will go on as she ages until, finally, no one from her parents’ generation will remain on this side of the veil.

The windblown leaves add a layer of seasonal allegory to all of this, as the poet approaches the autumn of her own life. Her leaf won’t fall this year perhaps, and hopefully not for some decades. But her time will come. Our lives feel long, but the slowness is a trick of perspective. The truth is in the leaves.

♦

The Tricycle Haiku Challenge asks readers to submit original works inspired by a season word. Moderator Clark Strand selects the top poems to be published in Tricycle with his commentary.

To see past winners and submit your haiku, visit tricycle.org/haiku

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.