I recently attended a workshop in New York with a lama who was teaching compassion meditation. Part of the approach was to clearly experience our own suffering as a step toward connecting with the suffering of others and radiating the wish for their liberation from it. At one point, a young friend of mine—Columbia University student with the confident ease and healthy glow of one who has grown up in a stable upper-middle-class home—raised his hand. He was, he said, having trouble with the meditation because he was too happy—he couldn’t locate any suffering in his life.

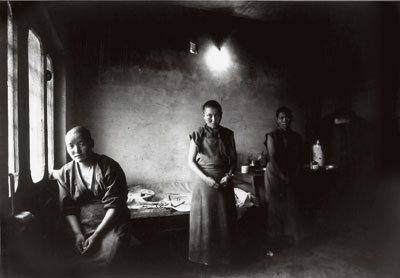

The people in Ellen Bruno’s films don’t have that problem. Bruno, a San Francisco–based relief worker and award-winning filmmaker, specializes in documenting the lives of men and (especially) women in the villages and cities of East Asia, where survival is a daily struggle. Her protagonists include lepers, child prostitutes, and Tibetan nuns. Her films portray a world of routine privation and oppression, essentially unchanged since the time of the Buddha.

The people in Ellen Bruno’s films don’t have that problem. Bruno, a San Francisco–based relief worker and award-winning filmmaker, specializes in documenting the lives of men and (especially) women in the villages and cities of East Asia, where survival is a daily struggle. Her protagonists include lepers, child prostitutes, and Tibetan nuns. Her films portray a world of routine privation and oppression, essentially unchanged since the time of the Buddha.

“I never intended to be a filmmaker,” Bruno said in a phone interview. “I grew up in a house without a TV and with little media consciousness. I was focused on community work, which I started doing in Mexico when I was fourteen.” Later, she worked in New York with Cambodian survivors of the Pol Pot genocide, which killed some 1.5 million people between 1975 and 1979. Many of the survivors suffered from severe psychosomatic diseases that they attributed to spirits, and Bruno made a short film to help doctors understand their perspective. As she heard more stories from the Cambodians, she started wondering how they endured such horrors, and then wanted to share what she had learned. She found herself becoming a Buddhist as well as a filmmaker, in spite of herself.

The result was Samsara (1989), which began as Bruno’s thesis project for an intensive one-year master’s program at Stanford and went on to win a passel of awards, including a Special Jury Award at Sundance. Shot in Cambodia after Pol Pot was deposed, it shows peasants telling their stories of the past genocide and their current hardships—being squeezed between the Khmer Rouge and the occupying Vietnamese, having legs blown off by mines left by both armies, and fighting the age-old threat of drought. (“The rice we plant is all we have. It if doesn’t rain, we starve.”) It is a life so grim that the thought of compassion becomes the only glimmer of light. As one young man says while searching through a former execution camp for records of his missing family, “We have been through such hardship and danger together. Now we must love one another. . . . We must stop being selfish, or we will betray the spirits of those who died here.”

Satya: A Prayer for the Enemy (1993) documents the oppression of young Tibetan nuns under Chinese rule. With a kind of matter-of-fact stoicism, refugees in Dharamsala describe the consequences of daring to protest the Chinese occupation: being tortured with electrical wires and cattle prods, chased out of their convents by Chinese policemen, gagged and raped. In one unforgettable scene strangely charged with both intimacy and violence, we see black-and-white footage from a police video of a demonstration. (Bruno told me that while the government cameraman was changing tapes he dropped one; a protester grabbed it and ran.) A stunned-looking policeman is shown staggering out a monastery gate as a nun clings to his shoulders, riding piggyback. Has he been beating her? Is he carrying her to safety or further abuse? Is she holding on by his order or in defiance?

This is what fascinates Bruno: the ambiguity of one-on-one relationships, despite our earnest political simplifications. “The nuns would remind me to check my outrage,” she says. “‘No, Ellen, they would beat us and beat us, then sip some water and pass the cup to us.’ In that gesture the two cease to be separate, and that’s where there’s hope.” Over the police video we hear a nun say, “The one who tortures me is made to believe that what he is doing is right. He must stay blind to my pain in order to carry on. At the end of the day he returns to his family. With arms that beat me he embraces his woman, wraps loving arms around his child, protecting her with his strength.”

One element that makes these brutal images bearable is Bruno’s lyrical visual style. Evolving beyond the more straightforward approach of her earlier work, she uses smeary slow-motion shots, glistening with burnished colors, that transcend the immediate image. The technique began, she told me, as an accident, when a friend in Dharamsala pressed the wrong button on her camera (a cheap one-chip consumer camcorder), opening the lens too wide. The result is that these unflinching contemplations of a world of sorrow become suffused with otherworldly beauty. The flame of a butter lamp, the turning of a prayer wheel or cotton spindle, the glowing embers of a cremation fire, the billowing of a nun’s robes—all hint at a sublime Existence behind this existence.

Bruno certainly needed that sublime element for her next two films—Sacrifice: The Story of Child Prostitutes from Burma (1998) and Leper: Life Beyond Stigma (2005). At fifty minutes, Sacrifice is her longest and most harrowing film. It was also the most heartbreaking and dangerous to shoot. In one of the brothels, she and her small crew were arrested. “We were taken to the police station and booked for trespassing. The police demanded our videotapes and started framing us on a drug charge. We had to sit there while they erased all our tapes from the past few days.”

Once again, we see people—this time Burmese village girls as young as five or six—victimized by forces bigger than themselves. Ethnic discrimination, the Myanmar dictatorship’s ruinous economic policies, and ignorance of the outside world lead them to trust adults who, promising jobs that will help them support their families, lure them to the cities of Thailand, only to imprison them in lives of sexual slavery. There, every business dinner is expected to end with a visit to the brothels, and the threat of AIDS is met not with condoms but with ever younger victims. Testifying to the camera, the girls relate tales of being sold repeatedly as virgins, beaten by drunks, exploited by police, and treated with occasional tenderness by men from their home provinces who recognize their accents. One girl who looks no older than fifteen tells us, “I slept with about a thousand men a year. . . . It was more than six years. You can figure out how many men I slept with. I’ve never been to school, so I can’t add it up.” Says Bruno, “When I finished shooting, I started cutting it and felt I couldn’t be around it any longer—it was so toxic—and put it aside for a few months.” Then she heard that this same girl had died. “I felt I had to put it together for her.”

The twelve-minute Sky Burial (2005), filmed in Drigung Monastery in northern Tibet, documents the rarely seen ritual of jha-tor, in which rogyapas,or “body breakers,” hack off the flesh of the dead and feed it to flocks of huge, impatient vultures. Aside from the chanting of monks and a short passage from the Tibetan Book of the Dead, this story is told without words, in a few simple camera setups (actually necessitated by Bruno’s being laid low by altitude sickness) that maintain a respectful distance from the dismembering of corpses. While it may sound horrific to Western ears, jha-tor makes sense in a country where arable land is scarce and being recycled into the ecosystem is understood as life-affirming. Why is being eaten by worms less objectionable? If one’s remains must be carried somewhere by something, why not into the sky, the symbol of infinite awareness-space, by vultures, whose high, effortlessly circling flight is a traditional exemplar of meditation?

In college, my vegetarian daughter found herself assigned to a campus job doing food prep in one of the dining halls, slicing and dicing meat. When I asked if she felt revulsion, she reminded me of an article we had once read in this magazine, where a rogyapa described the importance of maintaining a reverential attitude throughout the process. He did so, he explained, by reflecting that he would not want the person handlinghis remains to consider them disgusting. “I just remember that,” my daughter said.

It’s said that we should practice dharma as if our hair were on fire. Actually, our hair is on fire. Our bodies, our homes, our families, our cherished projects and institutions: all are doomed. One day, as in Planet of the Apes, the Statue of Liberty will be a bit of wreckage half buried in the sand. But with the comforts and entertainments of American life, we’ve so skillfully distracted ourselves that we can pretend—for a while—that the processes of decay are not inexorable. In our gleaming malls and cozy living rooms (and air-conditioned dharma centers) it’s easy to forget that our hair is on fire. Ellen Bruno’s films are a powerful reminder.

♦

Samsara: Survival And Recovery in Cambodia (1989)

Satya: A Prayer for the Enemy (1993)

Sacrifice: The Story of Child Prostitutes from Burma (1998)

Leper: Life Beyond Stigma (2005)

Sky Burial (2005)

Ellen Bruno, Director

Available at Brunofilms.com

$30 (DVD/VHS)

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.