Bangkok Tuesday, March 15th, 1993

After a twenty-two-hour flight from L.A. the Bangkok airport feels like a high-tech pit stop in an endless “bardo” tunnel.

Dazed and wrecked, my wife Lynn and I stumble through customs, only to be met unexpectedly by Prince Chatri, a member of the royal family. He had been notified of our arrival by an English-Italian movie producer who had asked me to direct a script I had written from one of my novels, Slow Fade. In the time-honored tradition of the Italian film industry, the producer had failed to show up to scout locations but at the last minute had provided a substitute. I had completely forgotten about the film plan, as we have been concentrating on Lynn’s assignment from a New York magazine to photograph the sacred Buddhist sites of Thailand, Burma, and Cambodia.

And then I remember the real reason we have come.

Nearly a year ago Lynn’s twenty-one-year-old son, Aryev, was killed in a car accident. To forget the wonder, the terror, the utter finality of this fact, even for a moment, is to experience it again as if for the first time. One of the perils of traveling which we would learn over and over again.

But after long weeks of solitude, we needed to break out, to become part of life again, to be far away from everyone and everything in order to be closer to what, in any case, we are going through.

We have survived by cutting our life down to the bone. The most ordinary gestures have become the most nourishing; the gaps between thoughts and memories the most necessary. But now, on the road, everything is on the clock. The outside has taken over from the inside and we don’t have enough spiritual muscle to resist. We bounce back and forth from paralysis to gathering information to compulsive distraction. Too many thoughts. Too many plans. Too many of the three Buddhist poisons: addiction, aversion, and delusion.

Ironic. Before landing, Lynn had been saying what a relief it was not to be on some kind of demented film trip, much more appropriate to be on a pilgrimage where we can allow all the levels of grief to unfold about Aryev’s death, a loss whose presence is inside us everywhere. But, once again, a film net has dropped over us. A part of me welcomes the intrusion. We are more exhausted and vulnerable than we thought we would be and it will be a relief to let others navigate for us. On the other hand, part of me feels compelled to push toward the margins of my “aloneness,” to give in to alienation, exhaustion, and grief, not to mention the odd unexpected moment of wonder.

The Buddha has a different take on solitude. Talking to the old monk Thera, in theTheranana Sutra, he says:

“I will tell you how to achieve complete solitude. In the solitude that I am talking about, Thera, all that which is past must be relinquished. All which is in the future must be relinquished. Desire and lust in the present must be fully mastered. This is the way, Thera,

that the true ideal of solitude can be completely realized . . . The sage who overcomes everything, who knows everything, who is attached to nothing, who is completely free because he has renounced everything, who is without thirst, he is the true sage. This man I call ‘one who lives alone.”’

We let Chatri, as he prefers to be called, guide us through customs. We are neither alone nor together, neither in the present nor the past.

Chatri is Thailand’s foremost film director, with more than forty films and several Thai “Academy Awards” to his credit. A delicate middle-aged man with a trim mustache, wearing faded jeans, untucked white shirt, and untied Adidas, he seems, at first, to possess all the distracted casualness of an aristocratic world-class hippie, and yet one soon becomes aware of his insatiable curiosity and energy as he maneuvers, with an almost ferocious focus, through the eccentric complexities of life in a city that seems on the verge of gridlock and breakdown.

Outside the terminal, we step into the hot humid night. No sense of the East. Only the busy stench of the West.

Dharma quotes swim up. I can’t stop them. They are beacons against my own subjectivity, which threatens, at times, to overwhelm me.

“In the sky there is no East or West. We make these distinctions in the mind, then believe them to be true….Everything in the world comes from the mind, like objects appearing from the sleeve of a magician.”—Lankavatara Sutra

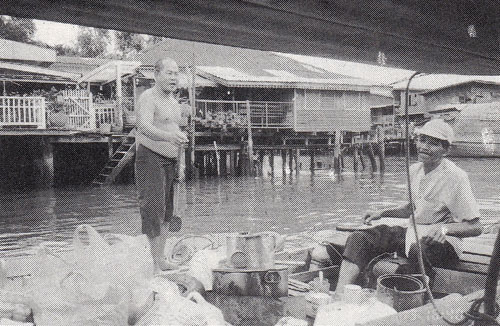

We settle into Chatri’s van, which not only transports him eyerywhere but also serves as his office, dining room, screening room, and family room. Immediately, we are wrapped in the greasy envelope of Bangkok. Welcome to the future, to the worldwide culture of Nikes, Big Macs, and bumper-to-bumper traffic endlessly creating paralysis, continual noise, and clouds of black car exhaust. The average speed of traffic in Bangkok is less than five miles per hour, and more than seventy percent of Thailand’s energy consumption is used for transportation. Everywhere the chaos of overpopulation, ugly high-rises, video stores, advertising. Everyone pluHard Travel to Sacred Placesgged into business-as-usual by cordless phones, faxes, videos. Consumerism run amok.

After an endless drive, we finally arrive at the Erawan Hyatt, a modern hotel in the middle of the city catering mostly to efficient Pacific Rim businessmen and stunned Western tourists.

In our room, we sleep fitfully, holding on to each other in our wretched dreams.

Waking in the middle of the night, I don’t know where I am. I remember the phone call in the middle of the night that told us Aryev had been in a car accident. . . in Arizona. . . He was driving all night to visit his father in Prescott and fell asleep.

Outside, there is still a hum of traffic, like a distant murmur of surf. Careful not to wake Lynn, I dress and go down to the lobby.

Outside I walk around the block, remembering the first line from one of Aryev’s last poems: “I’ve fallen in love with the slowness of time, stillness and perceptions dancing.”

We wake at five A.M. Outside, there is already a slow stream of traffic. Lynn is in bed, looking up at the ceiling, tears in her eyes, a strange half-smile on her lips.

We cannot leave the room. We will not leave the room. Where is my breathing? Where does it begin? Where does it end?

After breakfast, we walk down Ploenchit Road for a few blocks in the thick gray smog, past the Hindu shrine on the corner where pilgrims make wishes, no doubt for an air-conditioned car or a condo way above it all. Bangkok feels likeBlade Runner. A nightmare vision of the future. No air. No space. But everything and everyone busy. Buying, spending, scheming, and hustling.

Drenched with sweat and fear, we retreat to the hotel.

In the Nation, Bangkok’s English-language morning newspaper, a first glimpse of modern Thai Buddhism:

“An ex-monk, caught having sex with a female corpse in a coffin at a Samut Prakan temple in January, was jailed for two years and six months and fined a total of Btl,OOO [$40 U.S.] on Friday by the provincial court.

“However, judges Boonsong Noisopon and Lachit Chai-anong commuted the jail term by half after Samai Parnthong, 38, defrocked after the incident, pleaded guilty to the charge.

“Samai, who was accused of other offences, was sentenced to eight months jail for possessing 32.58 grammes of marijuana, two years for damaging other people’s property, fined Bt500 for engaging in a shameful act in public and fined Bt5000 for creating a public nuisance after getting drunk.

“But the ex-monk could not pay the fine and the court ordered that he serve an additional jail term instead at the rate of one day per Bt12, the standard rate for all offenders.

“On Jan. 20, after performing a religious ceremony at the funeral of a woman in her early forties at Ratpothong Temple in Samut Prakama’s Muang district, Samai sneaked into the coffin shortly before midnight.”

That night we go with Chatri to the annual film awards, Thailand’s version of the Oscars.

Chatri is not up for an award this year and we sit through the ceremonies with no one to root for. All through the ceremonies I think of Bertolucci’s new film, Little Buddha, and those parts of the script I wrote for him, a process which took almost a year and which ended with a bad case of burnout and self-recrimination. Writing the Bertolucci script, I felt nailed to the dichotomies of hope and fear. Sacred and profane. Success and failure. And I knew just enough about Buddhism to realize that I knew nothing at all. One evening in New York, when I was in the early stages of the script, I took Bertolucci to meet a Tibetan lama, Gelek Rinpoche, in an effort to satisfy a list of questions we had struggled with, questions about reincarnation and the laws of karma. Before answering our questions, Gelck Rinpoche looked at me and said abruptly: “The first thing you should do is take off your Buddhist clothes.” I was never really successful. My Buddhist clothes remained tightly wrapped around me, almost to the point of choking me. I could never let go of my self-consciousness of the task of writing about Buddhism for a mass audicnce. And I was too determined to please. I wasn’t enough of a Buddhist to drop being a Buddhist.

In the room, sudden grief and disorientation. Is it jet lag or my all-around exhaustion which causes a dive into such morose subjectivity? Or the poignancy of missing Aryev, who would have prowled these streets with such vitality and enthusiasm? All of them, no doubt. Plus the overwhelming certainty that we should be anywhere but in Bangkok.

But as the sutras say, I am everywhere and nowhere.

“What is born will die, what has been gathered will be dispersed, what has been accumulated will be exhausted, and what has been high will be brought low.”

In the morning newspaper:

“Once hidden from public view, alleged misconduct by Buddhist monks has increasingly made the headlines for the past several years to tarnish the image of the revered Sangha institution. This ranges from minor charges of fortune telling or giving tips on lottery numbers to serious charges of making personal gains from temple property or having sex with female worshippers.

“The latest controversy involves Phra Thep Silvisut, the abbot of Wat Arun Ratchawararam. The abbot recently allowed a political rightist group to make use of the temple facilities and made a public statement praising military strongman Gen. Suchinda Kraprayoon, as the ‘right person’ to become Thailand’s prime minister.

“In the eyes of several monks considered to be intellectuals among monks, the cause of the Sangha’s decline is that it has stood still while other parts of the society have been changing rapidly.

“For modern Thais, the Buddha’s teachings might sound absurd to people in modern society. But that is social ‘karma’ which reflects the ultimate truth of the Buddha’s teaching on the natural law of cause and effect:

As the seed, so the fruit

Do good, get good,

Do bad, get bad.

“Setting sight on the status of becoming a newly industrialized country, Thai society has adopted social values from the West. As a result, Thai people think that the desirable kind of progress is material progress.

“It has become a national passion to reach for that economic miracle. In so doing, it has created a cultural distortion which focuses on an ever-increasing rate of consumption. The whole Thai way of life is altered, leading to rejection of religion and a decline in morality. The Sangha institution, now neglected, finds itself cut off from all movements of the outside world.”

The next day, we sleep and order room service and stare vacantly out the window at the stalled traffic. We have hit a slump. Neither of us feels like continuing and we even contemplate flying back to our home in New York’s Hudson Valley or finding a place on the beach in southern Thailand for a few weeks. But we are obligated to fulfill Lynn’s photo assignment. Perhaps it is just as well, without obligations we would be no more than a matchbox on the ocean. Rather than being on a pilgrimage, even a failed one, we would be on a vacation, or worse, an adventure. And going back will be as arduous and melancholy as going forward, because most of the time we both know there isn’t any difference.

Our last night in Bangkok, Chatri and his wife Kamla take us on a tour of Patpong, Bangkok’s world-famous sex quarter. A blazing display of neon signs, sex shops, and nightclubs where every imaginable sexual variation is for sale. A hymn to desire. Full relief for your dollars from such clubs as the Playmate, the Pink Panther, the Lucky Strike Disco, etc. Sex, drugs, and rock ‘n’ roll. Every erogenous zone available for exploring, probing, penetrating. Even in this age of AIDS, the streets are jammed with American, European, and Japanese businessmen.

The whole scene is so consumer-oriented and busy that one feels curiously removed, like grazing through a huge supermarket.

The first club we enter is a new four-story Las Vegas style building hosting over a hundred young girls, most of them sitting on tiers behind a hundred-foot-high plate glass window. The girls are very beautiful in their elegant high-necked silk evening gowns. As they chat among themselves, they seem totally oblivious to the array of men staring at them through the window. The whole display is like an exotic zoo.

Sex and death. Pleasure and suffering. This and that. . .

“A man who does not pay attention where he walks will get bitten by a snake. Likewise, sensual desires constitute serious dangers for the present and the future.”

—Alagadadupama Sutra

Chatri is researching a film about a young prostitute from northern Thailand whose father sold her to a brothel when she was fourteen, apparently a common transaction among the poverty-stricken hill tribes. Most girls send money home, and more than three quarters of them, according to Chatri, will be dead of AIDS in three or four years. And yet this commerce goes on.

An interesting fact: Thailand has more than 250,000 monks and twice as many prostitutes.

We check out one of the rooms. A round bed with a round mirror overhead. A bidet in the corner. Everything neat and arranged.

We have Cokes in a darkly lit coffee shop while one of the girls demonstrates for us how she slips on a condom without the customer knowing it’s on. Taking the condom out of her purse in one fluid motion, she blows it up and places it smoothly over a salt shaker. She smiles sadly.

Sometimes a customer refuses to wear the condom and then she either jerks him off or gives him a blow job. She is eighteen, bored, and very professional. She has no regrets. It’s a living. “Karma,” Chatri explains matter-of-factly. “Nothing one can do.” And yet, like many Thais, he exists easily within many cultural contradictions, publicizing AIDS with his film and in newspaper interviews, spending time in hospitals with AIDS patients, and even carrying condoms on his key chain complete with instructions and information about this epidemic which has already claimed hundreds of thousands of lives.

Families as well as customers eat in the brothel’s coffee shop. CNN on the huge TV. Unlike the West, there is no puritanical separation, no rigid duality between right and wrong.

We visit a few other clubs. The most beautiful girls I have ever seen are dancing in white French lace bras and bikini underwear on top of a circular bar, their movements bored and solipsistic as they gently sway their hips to Diana Ross and the Supremes. They wear plastic tags with large numbers around their necks so that they can be easily identified. They also wear pendants on silver and gold chains engraved with images of the Buddha, which they take off only when they are servicing a customer.

Another club offers a live sex show between a bored young couple assuming three or four sexual positions in rapid succession. Afterward, the woman smokes a cigarette between the lips of her vagina.

In another act, her partner, a handsome boy dressed in black leather, cracks a whip over her ass. They are a married couple. The man is a high school teacher during the day, a sex performer at night. He makes more in one week at the club than in a year teaching school. But the burnout is extreme. He has to “get it up” eight times a day and doesn’t know how long he can keep doing it.

In a dark low-ceilinged bar packed wall-to-wall with customers, Chatri speaks to the owner, a plump man in a white suit smoking a huge cigar.

The owner motions to one of the girls, who climbs on top of the bar, takes off her bikini briefs, and sticks a large crayon up her vagina. Placing a piece of white paper underneath her, she moves her pelvis around, writing “I love you Rudy” in big red letters. Then she hands me the paper. When I offer her some money, she refuses. “It is a gift.”

The last bar we visit is gay. Pretty young boys dancing together surrounded by middle-aged Western men. The dancers’ eyes are drugged and listless. Many of them have AIDS.

The fat German sitting next to me slowly strokes the thigh of a boy who can’t be more than fifteen. The German tells him how much he loves him. “Five hundred baht,” the boy says. Twenty dollars. “Then I love you, too.”

We walk away from Patpong. A manifestation of hell, where death is a potential partner in any transaction and life seems less than impermanent.

The next morning, before sunrise, we leave for Chiang Mai by way of Sukhothai, the thirteenth-century capital of the first large Thai kingdom in Siam, with a stop planned at Tham Krabok, a rehab monastery. Chatri has provided us with a van and a driver, and his brother-in-law, Gee and Anna, his girlfriend also come along. Even though we leave before five A.M., it takes several hours of driving through the usual congested traffic to finally free ourselves of Bangkok.

It is a long boring drive over a straight, well-paved highway, past dry parched fields, an occasional rice paddy, modern gas stations and sandwich shops.

After four hours we pull into Tham Krabok, a temple complex visible from the road surrounded by craggy limestone hills. Tham Krabok means “Opium-Pipe Cave Monastic Center.” Its main function is as a detox haven for people with a wide variety of addictions, from opium and crack to alcohol and even cigarettes. It is famous for having cured tens of thousands of drug addicts from Thailand as well as many other countries, including the West and Australia. Lately the government has claimed that the Abbot, Phra Chamroon Panchan, who was a policeman before he became a Buddhist monk, is allowing Tham Krabok to harbor illegal Lao immigrants who are trying to coordinate subversive activities against the Communist government in Vientiane. Phra Chamroon denies all charges, saying that the 13,000 Hmong tribesmen in his community were all involved in the opium trade in the Golden Triangle and couldn’t care less about overthrowing the Laotian or any other government.

I feel immediately at home at Tham Krabok, being somewhat of an aficionado of dukkas, or cravings; an excellent place to contemplate the five central facts of Buddhism:

1. I am subject to decay, and I cannot escape it.

2. I am subject to disease, and I cannot escape it.

3. I am subject to death, and I cannot escape it.

4. There will be separation from all that I love.

5. I am the owner of my deeds. Whatever deed I do, good or bad, I shall become heir to it.

The whole place is funky and bare-bones. Walking down a dirt path toward the main temple, we pass a huge black-iron Buddha sitting at the head of a rock quarry surrounded by rusting machinery as well as twenty five statues of his main disciples, all made from iron. Behind the quarry, a rocky mountain is surrounded by thick jungle.

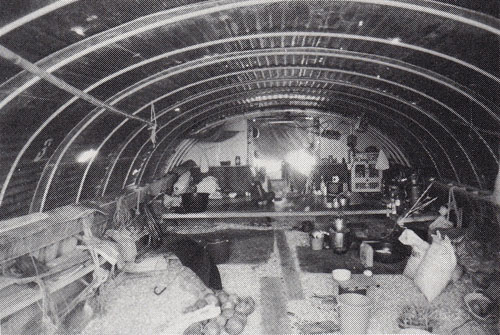

Tham Krabok was founded by Mae-chii Mian, a Buddhist nun. Twenty-five percent of the three-hundred-person staff are nuns, the rest monks. All monks or nuns help with the program and over half have been addicts themselves.

We sit at a small stone table in the shade of a huge tree, watching the patients lounge around languidly in their red cotton pants behind a closed courtyard, while others seem free to wander around the compound, smoking cigarettes and chatting among themselves.

Most of them seem to be teenagers or in their twenties. A lot of them have intricate tattoos. Seventy percent, we learned later, are Asian, mostly from Thailand, Burma, and Cambodia, while the rest are Westerners. No women are visible; they must be in separate quarters.

The main part of the program involves an emetic herbal treatment, which is composed of 150 different herbs. For five days every morning the patient drinks a thick concoction, followed by a sauna in the afternoon and then, in the evening, the patients gather for a group vomiting, kneeling in lines in front of a long cement trough puking their guts out. The session is often accompanied by loud pulsating music played by other patients who have already gone through this part of the process. After five days of sweating and vomiting there follows another twenty-five days of meditation, herbal saunas, and counseling. Before being admitted, the potential patient takes a vow which commits him to abide strictly by the rules of the monastery.

He writes the vow on a piece of rice paper and then swallows it. If he breaks even one rule, he is immediately thrown out and can never come back again. It’s hardball, all or nothing, and for the most part, it seems to work, as Chamroon claims a success rate of over seventy percent.

A black American monk, Gordon, or Monk Gordon, as he prefers to be called, broke it down further for us. “I’ll tell you one thing, dude, most of the people who go back on their vow seem to die. Tanha [grasping or desire] is tough, baby. No prisoners. That’s the way it is when you’re dealing with tanha or dukka. We got all kinds coming here from all over the world. We group them according to their religion and sex. We change their name, give them vegetarian food, and put them through the process. We have one monk for every ten addicts. That’s first-class treatment anyhow you cut it.”

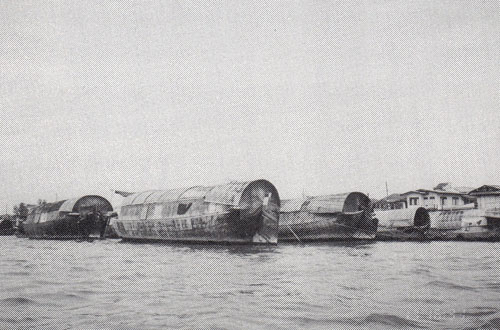

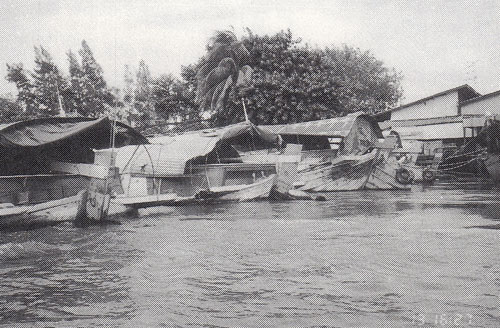

This is the first of two excerpts adapted from a book of the same name, to be published in the fall by Shambhala Publications. The first installment features extracts of a travel journal written in Thailand; the second excerpt, which picks up the journey in Burma and Cambodia, will appear in the Summer Issue. Snapshots by the author.

Being a monk at Tham Krabok demands discipline. Aside from dealing with the addicts, there are other chores, such as breaking rock at the quarry, making your own robes, cutting wood, planting rice, growing the herbal plants (the mixture of which is a secret), and building and repairing all the structures on the 350-acre grounds, not to mention finding time to meditate. When I ask Monk Gordon about vipassana, or insight meditation, he says they all do it but in different ways. The most common way of measuring how long to meditate is by how long it takes to burn an incense stick, or cello—somewhere around forty minutes. He himself is a “five-hundred-stick-a-year man.”

The monks also eat only one meal a day and renounce all forms of transportation except walking. Every year just before the Rains Retreat, the monks go onthudong, or forest walking, for a few weeks, taking only a parasol and a mosquito net. They sleep on the forest floor and never stay in one place more than a night.

Abruptly, Monk Gordon stands up. “I don’t say goodbye,” he says. “I only say hello.”

Turning away from us, he walks down the path.

After a six-hour drive, we arrive at the Sukhothai Hotel, a large two-story cement pile with rooms set around a circular courtyard, a large swimming pool in the middle. Perhaps because this is the hot season no one is about. The whole place feels sterile and oddly fascistic. It reminds me of the Japanese hotel in Lumbini, near Siddhartha’s birthplace, Kapilavastu, in what is now southern Nepal. Cold, charmless, antiseptic: constructed for large tour groups who just want to bop into one of the major Buddhist holy spots, grab some “merit,” snap a few photos, buy a souvenir or plastic relic to take home, and sayonara, on to Bodhgaya or Boudnath or Borabudur, other stops on the pilgrimage circuit.

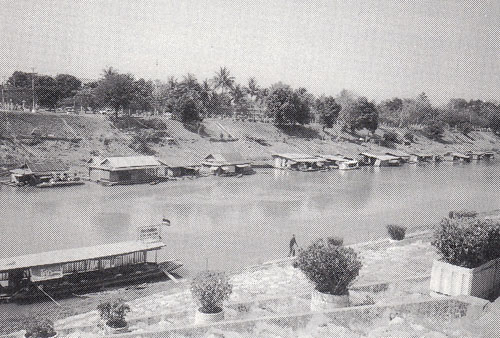

The next morning Lynn has already left when I take a taxi out to the ruins, passing the Yom river, which flows through the entire site, over fifty miles across a flat plain bordered by low mountains in the far distance. The city was the center of a kingdom that included Luang Prabang on the Mekong river in Laos, lower Burma, and Malacca in Malaysia.

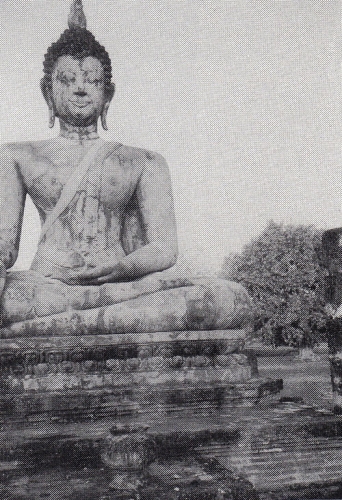

At Wat Mahathat, I catch a glimpse of Lynn’s head, her long white hair bowed like a silver curtain over her camera as she stands before a statue of a standing Buddha over thirty feet tall. Around her are large broken columns and chedis, called stupas in India and Tibet, pagodas in southeast Asia. Most of the chedis in Thailand, as in Burma, Sri Lanka, and Cambodia, have a greater sense of verticality than the Indian or Tibetan stupas. The chedis of Sukhothai are made out of laterite, a building material of red-colored porous soil which hardens when exposed to the air.

I watch Lynn as she stands without moving, contemplating the huge Buddha with its oval head bearing a crown, its face dominated by a serenely transcendent smile. Perhaps, for a moment, she has found relief and acceptance of her grief.

Walking around the statues and chedis, almost all of which have collapsed, I find a position in front of a “walking” Buddha, a figure that I have never seen before and which is, in fact, not found in many other periods. This one is positioned on a raised stone platform, its left hand raised in the “attitude of dispelling fear,” the thumb and forefinger delicately joined, the right leg stepping forward, the left heel rising in the process.

But it is the elegance of the slightly curving right hand that holds me.

Open and yet hesitant, vulnerable and at the same time reflecting the courage of “walking on,” the totally relaxed fingers are androgynous, beyond gender, neither coming nor going, but endlessly becoming. Even so, the fingers seem to beckon. They are slightly seductive, tantalizing, inviting. Not at all the stern detachment of Indian or even Tibetan Buddhist sculpture. I look up at the face, at the erect confident posture of the body. The whole expression, from the delicately turning fingers to the mysterious beatific smile, is one of total equanimity. The figure walks forward as if within an illuminated dream. The journey is not revealed, because it cannot be told and cannot appear. It is a “flight through the air” of one who no longer needs to move at all in order to be anywhere.

The movement seems beyond grace. Its aesthetic demands contemplation, a focus that suddenly fills me with shock. The Buddha seems to be walking right through me. It is a levitation that is more than I can assimilate. The Amitayur-Dhana Sutra is explicit: if you ask how is one to behold the Buddha, the answer is that you have done so only when the thirty-two major and eighty minor characteristics have been assumed in your own heart.

But I can’t name these characteristics. I can’t recognize or inhabit them. My mind is too ignorant, too cluttered and conceptual. My heart too full of unassimilated closures and weird obscurations. I’m still a “road junky” looking for sensations, for adventure. Even, god forbid, for entertainment. I can look. I can be thrilled. I can be appreciative. But can I endlessly be?

I close my eyes and open them again. The Buddha is still there, but I am somewhere else.

To be continued in the Summer issue.

Monk Gordon is a broad-shouldered, middle-aged ex-junky from Harlem who has fought as a mercenary in the Falkland Islands, South Africa, and Cambodia, as well as in Vietnam. As the only resident foreign senior monk among the monastery’s clergy, he has made a vow to stay for life and has already been at Tham Krabok for over ten years.

His approach is straightforward. No bullshit, no “idiot compassion.” He gets the job done. “We mostly get them eight to forty-five years old. The younger the better. Lot of these kids got strung out from their mama blowing opium up their nostrils to chill them out. Lot of them coming down from the Golden Triangle. Not to mention the South Bronx.”

Each patient gets five visits and then only from a relative, for not more than twenty minutes. “We watch them. They blow this chance, most likely they blow it all.”

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.