When Brice Marden saw the “Masters of Japanese Calligraphy” exhibition at New York’s Asia Society in 1984, he was so captivated by the beauty and authority of the work, by the living energy of the drawn lines, that he kept a copy of the catalogue with him wherever he went. For the first time, he saw calligraphy as drawing. And drawing for Marden—like calligraphy for the Japanese and Chinese—is “the most direct form of all artistic expression.” Long a believer that art is a form of spiritual communication, Marden felt an affinity with this work, which evolved in a kind of inspired state. In fact, the Chinese expression for a piece of Zen calligraphy is “heart print.”

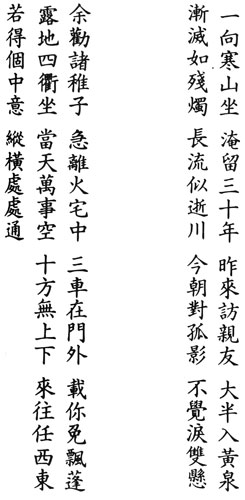

Yet the meaning of calligraphy as words remained elusive. Marden turned to translations of Li Po (705-762 C.E.) and Tu Fu (712-770 C.E.) but he had a revelation when he received a copy of Red Pine’s translations of poems by Cold Mountain (Han Shan, early T’ang Dynasty). With English-language versions on one page and Chinese calligraphy on the facing page, the book provided a way to connect the visual form of the Chinese characters with the spiritual and emotional content of the language: “I did drawings using the form that the poems take in the Chinese, then I started joining image and calligraphy as a skeleton.”

Marden was compelled not only by the beauty of the poetry but also by the story of Han Shan’s life. The poet abandoned his wife and a son and traveled over 750 miles from a comfortable home in Imperial China to live as a hermit on Cold Cliff in T’ien-t’ai. He took up residence in a pine hut roofed with bamboo leaves, cooked greens over a weak fire, and slept in a caved-in bed. And while he never ceased striving to become a holy man, Han Shan continued to experience—and write about—the pain of being separated from his family. The eminent translator Arthur Waley once wrote, “Cold Mountain is often the name of a state of mind rather than of a locality. It is on this conception, as well as on that of the ‘hidden treasure,’ the Buddha who is to be sought not somewhere outside us, but ‘at home’ in the heart, that the mysticism of the poems is based.”

Marden’s six Cold Mountain paintings took almost three years to complete. The artist evolved a new method: unlike the layered oil and wax surfaces of earlier works, which had masked misstep, indulgence, and painterly invention, Marden decided to keep his materials thin. To this end, he methodically scraped and sanded pigment after every brush stroke. Each canvas, calloused with corrections and eroded by erasure, lays open a vast accumulation of decisions. It is this openness, this exposure—not just of the creative process but of the self—that Marden painted into Cold Mountain: “To be an artist is to do your work and let your work express the evolution of a vision …. We move toward that something along a visual path. It’s the opposite of knowing yourself through analysis. It’s more like knowing yourself by forgetting about yourself, learning to be not so involved with yourself.”

Adapted, with permission of the author and publisher, from Brenda Richardson’s “The Way to Cold Mountain,” in the monograph Brice Marden/Cold Mountain (Houston: Houston Fine Art Press, in cooperation with Dia Center for the Arts, Walker Art Center, The Menil Collection, 1992).

once I got to Cold Mountain

I stayed thirty years

finally looking up family and friends

most had entered the Springs

slowly fading like a sputtering candle

or far flowing like a passing stream

this morning facing a solitary shadow

suddenly two tears welled

—Han Shan

Red Pine 53

children I implore you

leave the burning house

three carts wait outside

to take you away from this mess

sit at the crossroads on open ground

before the sky everything’s empty

no high or low in any direction

come and go east and west

if you understand what I’m saying

you can go anywhere when you’re free

—Han Shan

Red Pine 253

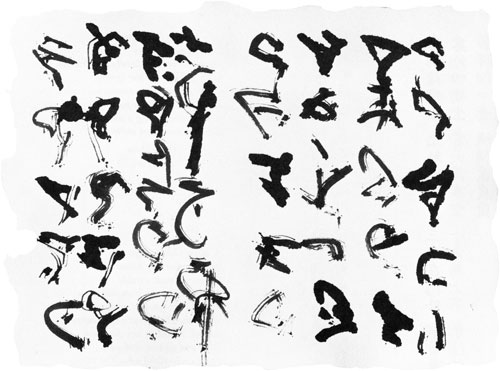

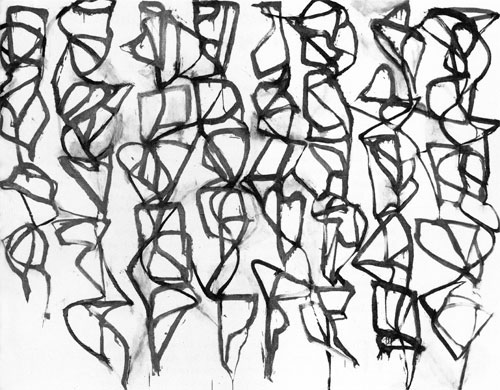

From Group of Five, Cold Mountain, by Brice Marden, ink on paper, 1988

Courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery, NY

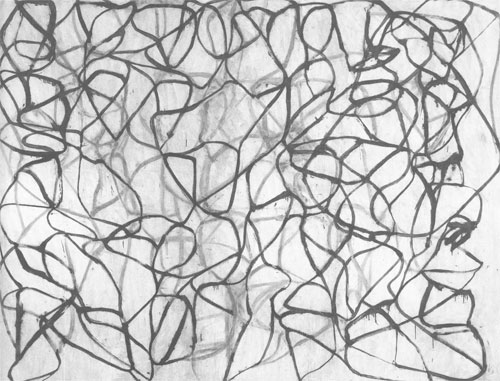

Cold Mountain 5 (Open), by Brice Marden, oil/linen, 1988-91

Cold Mountain 5 (Open), by Brice Marden, oil/linen, 1988-91

Courtesy Mary Boone Gallery, NY

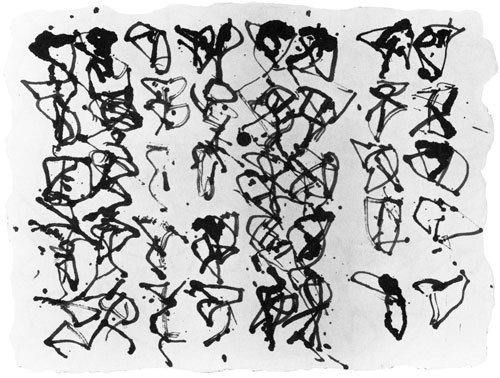

From Group of Five, Cold Mountain, by Brice Marden, ink on paper 1988

Courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery, NY

Cold Mountain 1 (Path), by Brice Marden, oil/linen, 1988-89

Cold Mountain 1 (Path), by Brice Marden, oil/linen, 1988-89

Courtesy Mary Boone Gallery, NY

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.