Throughout its history, Buddhism has worked as a civilizing force. Its teachings on karma, for instance—the principle that all intentional actions have consequences—have taught morality and compassion to many societies. But on a deeper level, Buddhism has always straddled the line between civilization and wilderness. The Buddha himself gained awakening in a forest, gave his first sennon in a forest, and passed away in a forest. The qualities of mind he needed in order to survive physically and mentally as he went, unarmed, into the wilds were key to his discovery of the dharma. They included resilience, resolve, and alertness; self-honesty and circumspection; steadfastness in the face of loneliness; courage and ingenuity in the face of external dangers; compassion and respect for the other inhabitants of the forest. These qualities formed the “home culture” of the dharma.

Periodically, as Buddhism adapted to different societies, some practitioners felt that the original message of the dharma had become diluted. So they returned to the wilderness in order to revive its home culture. Many wilderness traditions are still alive today, especially in the Theravada countries of Sri Lanka and Southeast Asia. There, mendicant ascetic monks continue to wander through the remaining rain forests, in search of awakening in environments similar to that in which the Buddha became awakened himself. Among these traditions, the one that has attracted the largest number of Western students, and is beginning to take root in the West, is the Kammatthana (Meditation) forest tradition of Thailand.

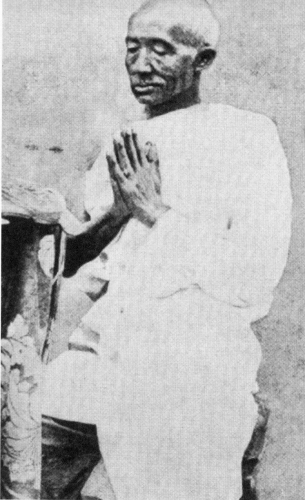

The Kammatthana tradition was founded by Ajaan Mun Bhuridatto (Ajaan is Thai for “teacher”) in the early decades of this century. Ajaan Mun’s mode of practice was solitary and strict. He followed the Vinaya (monastic discipline) faithfully and also observed many of what are known as the thirteen classic dhutanga (ascetic) practices, such as living off almsfood, wearing robes made of cast-off rags, dwelling in the forest, and eating only one meal a day. Searching out secluded places in the wilds of Thailand and Laos, he avoided the responsibilities of settled monastic life and spent long hours of the day and night in meditation. In spite of his reclusive nature, he attracted a large following of students willing to put up with the hardships of forest life in order to study with him.

Ajaan Mun also had his detractors, who accused him of not following traditional Thai Buddhist customs. He usually responded by saying that he wasn’t interested in bending to the customs of any particular society—as they were, by definition, the customs of people with greed, anger, and delusion in their minds. He was more interested in finding and following the dharma’s home culture, or what he called the customs of the Noble Ones: the practices that had enabled the Buddha and his disciples to achieve awakening in the first place. This term—the customs of the Noble Ones—comes from a story in which the Buddha’s father upbraids his son for living in the forest and going for alms, things that the customs of their family regarded as shameful. The Buddha’s response: “I now belong, not to the lineage of my family, but to the lineage of the Noble Ones. Theirs are the customs I follow.”

Ajaan Mun devoted most of his life to tracking those customs down. Born in 1870, the son of rice farmers in the northeastern province of Ubon, he was ordained as a monk in 1892. At that time there were two broad types of Buddhism available in Thailand. The first can be called Customary Buddhism—the mores and rites handed down over the centuries that, for the most part, taught monks to live a sedentary life in the village monastery, serving the local villagers as doctors or fortunetellers. Monastic discipline tended to be loose. Occasionally, monks would go on a pilgrimage they called “dhutanga,” but which bore little resemblance to the classic ascetic practices. Instead, it was more an undisciplined escape valve for the pressures of sedentary life. Moreover, monks and laypeople practiced forms of meditation that deviated from the path of tranquility and insight outlined in the Pali canon. Their practices, called vichaa aakhom, or incantation knowledge, involved initiations and invocations used for shamanistic purposes, such as protective charms and magical powers. They rarely mentioned nirvana except as an entity to be invoked in shamanic rites.

Ajaan Mun devoted most of his life to tracking those customs down. Born in 1870, the son of rice farmers in the northeastern province of Ubon, he was ordained as a monk in 1892. At that time there were two broad types of Buddhism available in Thailand. The first can be called Customary Buddhism—the mores and rites handed down over the centuries that, for the most part, taught monks to live a sedentary life in the village monastery, serving the local villagers as doctors or fortunetellers. Monastic discipline tended to be loose. Occasionally, monks would go on a pilgrimage they called “dhutanga,” but which bore little resemblance to the classic ascetic practices. Instead, it was more an undisciplined escape valve for the pressures of sedentary life. Moreover, monks and laypeople practiced forms of meditation that deviated from the path of tranquility and insight outlined in the Pali canon. Their practices, called vichaa aakhom, or incantation knowledge, involved initiations and invocations used for shamanistic purposes, such as protective charms and magical powers. They rarely mentioned nirvana except as an entity to be invoked in shamanic rites.

The second type of Buddhism available at that time was Reform Buddhism, based on the Pali canon. This began in the 1820s with Prince Mongkut, who later became King Rama IV (and still later was portrayed in the musical The King and I) Prince Mongkut was a monk for twenty-seven years before ascending the throne. After studying the canon during his early years as a monk, he grew discouraged by the level of practice he saw around him in Thai monasteries. So he reordained among the Mons, an ethnic group that straddled the Thai-Burmese border and occupied a few villages across the river from Bangkok, and studied Vinaya and the classic dhutanga practices under the guidance of a Mon teacher. Later, his brother, King Rama III, complained that it was disgraceful for a member of the royal family to join an ethnic minority, and so built a monastery for the prince-monk on the Bangkok side of the river. There, Mongkut attracted a small but strong following, and in this way the Dhammayut (lit., “In Accordance with the Dharma”) movement was born.

In its early years, the Dhammayut movement was devoted to studying the Pali canon, with emphasis on the Vinaya; following the classic dhutanga practices; developing a rationalist interpretation of the dharma; and reviving meditation techniques taught in the Pali canon, such as recollection of the Buddha and mindfulness of the body. None of the movement’s members, however, could prove that the teachings of the Pali canon actually led to awakening. Mongkut himself was convinced that the path to nirvana was no longer open, but that a great deal of merit could be made by reviving at least the outward forms of the earliest Buddhist traditions. Formally taking a Bodhisattva Vow, he dedicated the merit of his efforts to future buddhahood. Many of his students also took vows, hoping to become disciples of that future Buddha

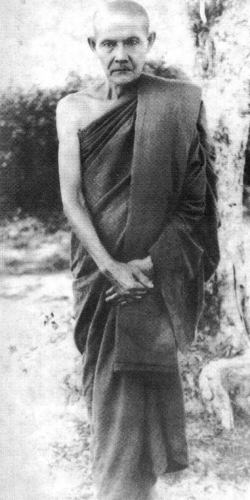

Upon disrobing and ascending the throne after his brother’s death in 1851, Rama IV was in a position to impose his reforms on the rest of the Thai sangha, but chose not to. Instead, he quietly sponsored the building of new Dhammayut centers in the capital and the provinces, which was how—by the time of Ajaan Mun—there came to be a handful of Dhammayut monasteries in Ubon. Feeling that Customary Buddhism had little to offer him, Ajaan Mun joined the Dhammayut order. Unlike many who joined the order at the time, he wasn’t interested in the social advancement that would come with academic study and ecclesiastical appointments. Instead, his life on the farm had impressed on him the sufferings inherent in the cycle of life and death, and his single aim was to find a way out of the cycle. As a result, he soon left the scholarly environment of his preceptor’s temple and went to live with a teacher named Ajaan Sao Kantasilo (1861-1941) in a small meditation monastery on the outskirts of town.

Ajaan Sao was unusual in the Dhammayut order in that he had no scholarly interests but was devoted to the practice of meditation. He trained Ajaan Mun in strict discipline and canonical meditation practices, set in the context of the dangers and solitude of the wilderness. He could not guarantee that this practice would lead to the noble attainments, but he believed that it headed in the right direction.

After wandering for several years with Ajaan Sao, Ajaan Mun set off on his own in search of a teacher who could show him for sure the way to the noble attainments. His search took nearly two decades and involved countless hardships as he trekked through the jungles of Laos, central Thailand, and Burma, but he never found the teacher he sought. Gradually he realized that he would have to follow the Buddha’s example and take the wilderness itself as his teacher, not simply to conform to the ways of nature—for nature is samsara itself—but to break through to truths that would transcend them entirely. If he wanted to find the way beyond aging, illness, and death, he would have to learn the lessons of an environment where aging, illness, and death are thrown into sharp relief. At the same time, his encounters with other monks in the forest convinced him that learning the lessons of the wilderness involved more than just mastering the skills of physical survival. He would also have to develop the acuity not to be misled by dead-end sidetracks in his solitary meditation. So, with a strong sense of the immensity of his task, he returned to a mountainous region in central Thailand and settled alone in a cave.

In the long course of his wilderness training, Ajaan Mun learned that contrary to Customary and Reform beliefs, the path to nirvana was not closed. The true dharma resided not in old customs or texts but in the well-trained heart and mind. The texts were pointers for training, nothing more or less. The rules of the Vinaya, instead of simply being external customs, played an important role in physical and mental survival. As for the dharma texts, practice was not just a matter of confirming what they said. Showing true respect for the texts meant taking them as a challenge: putting their teachings seriously to the test to see if, in fact, they did bring release from suffering. In the course of testing the teachings, the mind would come to many unexpected realizations that were not contained in the texts. These in turn had to be put to the test as well, so that one learned—and attained—gradually, by trial and error. Only then, Ajaan Mun would say, did one understand the dharma.

When Ajaan Mun had reached the point where he could guarantee that the path to the noble attainments was still open, he returned to the Northeast to inform Ajaan Sao and then to continue wandering. Gradually he began to attract a grassroots following. People who met him were impressed by his demeanor and teachings, which were unlike those of any other monk they had known. They believed that he embodied the dharma and Vinaya in everything he did and said. As a teacher, he took a warrior’s approach to training his students. Instead of simply imparting verbal knowledge, he put his students into situations where they would have to develop the qualities of mind and character needed for surviving the battle with their own defilements. Instead of teaching a single meditation technique, he taught them a full panoply of skills—as one student said, “Everything from washing spittoons on up”—and then sent them into the wild.

It was after Ajaan Mun’s return to the Northeast that a third type of Buddhism—State Buddhism, which emanated from Bangkok—began to impinge on his life. In an effort to present a united front in the face of imperialist threats from Britain and France, Rama V (1868-1910) wanted to move the country from a loose feudal system to a centralized nation-state. As part of his program, he and his brothers—one of whom was ordained as a monk—enacted religious reforms to prevent the encroachment of Christian missionaries. Having received their education from British tutors, they created a new monastic curriculum that subjected the dharma and Vinaya to Victorian notions of reason and utility. Their new version of the Vinaya, for instance, was a compromise between Customary and Reform Buddhism, designed to counter Christian attacks that monks were unreliable and lazy. Monks were instructed to give up their wanderings, settle in established monasteries, and accept the new state curriculum. Because the Dhammayut monks were the best educated in Thailand at the time—and had the closest connections to the royal family—they were enlisted to do advance work for the government in outlying regions.

In 1928, a Dhammayut authority unsympathetic to meditation and forest wanderers took charge of religious affairs in the Northeast. Trying to domesticate Ajaan Mun’s following, he ordered them to establish monasteries and help propagate the government’s program. Ajaan Mun and a handful of his students left for the North, where they were still free to roam. In the early 1930s, AJaan Mun was appointed the abbot of an important monastery in the City of Chiang Mai, but fled the place before dawn the following day. He returned to settle in the Northeast only in the very last years of his life, after the local ecclesiastical authorities had grown more favorably disposed to his way of practice. He maintained many of his dhutanga practices up to his death in 1949.

It wasn’t until the 1950s that the movement he founded gained acceptance in Bangkok, and only in the 1970s did it come into prominence on a nationwide level. This coincided with a widespread loss of confidence in state monks, most of whom were little more than bureaucrats in robes. As a result, Kammatthana monks came to represent, in the eyes of many monastics and laypeople, a solid and reliable expression of the dharma in a world of fast and furious modernization.

Buddhist history has shown that wilderness traditions go through a very quick life cycle. As one loses its momentum, another often grows up in its place. But with the wholesale destruction of Thailand’s forests in the last few decades, the Kammatthana tradition may be the last great forest tradition that Thailand will produce. Fortunately, we in the West have learned of it in time to gather lessons that will be helpful in planting the dharma’s home culture on Western soil, and establishing authentic wilderness traditions of our own.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.