Beyond the fringe of urban farmland, where radish and rice fields meet pine-forested hills, stands an ancient temple in northwestern Kyoto called Daikaku-ji, or Big Enlightenment Temple. This venerable site is the birthplace of the Shingon sect, founded in the ninth century by Kukai, the famous saint, scholar, and poet. Daikaku-ji is also the former summer palace of Emperor Saga, a ruler of the same era who loved and preserved the arts. Together with Kukai, Emperor Saga is credited with ushering in the Heian Period, a golden era of artistic and cultural achievement lasting three hundred years. Today, eleven hundred years later, Daikaku-ji is not only a prominent historical temple, but also the international headquarters of the Saga Goryu School of Ikebana.

The word ikebana, commonly translated as “Japanese flower arranging,” literally means “to preserve living flowers,” or “to preserve the essence of nature in a vase.” Through learning a complex system of rules, artistic principles and symbolic meaning, and by observing the beauty and quietude of nature, the ikebana practitioner strives to incorporate Buddhist concepts of peace, harmony, and reverence into daily life. Pursuit of the spiritual through the art of flower arranging is the greater study of kado, the way of the flowers.

Although Japan has various schools of ikebana, the Saga Goryu school is said to be one of the oldest. The story goes that one day Emperor Saga picked a handful of chrysanthemums growing on one of the two islands in the middle of Osawa Pond (a tiny lake on the grounds of Daikaku-ji), and arranged the flowers in a three-tiered manner depicting heaven, earth, and man. Thus the Saga school was born.

Nestled among pagodas and stone statues of Buddha, Osawa Pond has changed little from days of yore. Depending on the season, sightseers come from all over Japan to view flowering cherry trees, famous screens and scrolls, or the reenactment of Heian Period customs when aristocrats—ladies wearing twelve silk kimonos in harmonious shades—languished in phoenix-prowed boats. In autumn the inner temple gardens are filled with giant chrysanthemums, the national flower and symbol of royalty. The towering plants, pruned into heaven, earth, man configuration, line the perimeters of white stone gardens and creaking, centuries-old verandahs.

To view the inner sanctuaries, visitors enter the Daikaku-ji complex over stone bridges thick with moss and lichen. In November, crimson-red Japanese maples adorn paths leading to the mammoth wood door. Inside, winding walkways, enhanced with carved balustrades and gold hinges, zigzag across moss gardens and end at either shrines, viewing verandas, or dark corners. The temple, connected to the school and student dormitories by stepping stones or meandering and embellished corridors, presents a disorienting triangular layout where monks and laypeople work, study, and practice Shingon Buddhism, a sect that utilizes chanting, visualization, and special body postures to achieve enlightenment.

A typical day begins at 5:00 a.m. with a call to morning service. Worshipers gather in a large tatami-matted meditation hall and wait for the monks to arrive. When the shoji doors open, everyone bows their head to the mat while a parade of priests—each one wearing a black silk kimono, a white under-kimono, white tabi (opaque split-toed silk stockings), and a saffron cloth uniformly draped over the left shoulder—flies into the room. At the collar of these traditional robes, where layers of white, black, and saffron meet in a clean flat fold, a wooden fan sticks up like a carp fin.

The monks take their places within the inner sanctuary, a separate area cordoned off by a low black railing. Images of Dainichi Nyorai (the universal Buddha), shogonkas (formal flower arrangements common to Buddhist shrines), and glittering gold objects that symbolize the radiance of enlightenment adorn the altar. As the priests sit on their heels and arrange long billowy sleeves, the only sound is the rustle of silk falling in graceful folds. Simultaneously they arrive at correct and poised postures while a young monk performs a ritual of transporting a sacred text from the altar to the presiding monk. A novitiate begins chanting theHannyaharamita shingyo and is joined by the full-throated warbling of the others. The deep melodic male voices, synchronized into rhythmical tones and cadences, heighten the sacred atmosphere in which the Three Mystic Practices of correct body posture, cultivation of faith through meditative concentration, and divine chanting are employed.

After morning service, visitors, lay students, and monks dine together in the temple cafeteria on a typical breakfast of rice, fish, pickled vegetables, and tea. The light and healthy cuisine complements the discipline of religious worship and the study of kado, a series of ikebana classes that begin by introducing the twenty-eight prohibitions for choosing and pruning plant material. Many of these rules can be interpreted symbolically and act as a guide for not only flower arranging, but proper living.

- Don’t arrange flowers without knowing their names. (This shows lack of respect for the plant.)

- Don’t use entangled branches. (This reminds us of rebellion against one’s parents and goes against the teachings of Confucius.)

- Don’t use branches that point straight up to heaven; don’t use branches that point to earth, our mother; and don’t use flowers that point to each other. (Heaven, earth, and man are considered sacred and to point at them would be considered rude.)

- Don’t use branches that are even, as they will be in conflict with each other. (One path gives clarity, but two will create confusion.)

- Don’t use branches that have two outgrowths going in opposite directions. (This will create conflict, which goes against the principle of harmony.)

- Don’t go against the plant’s natural growth. (Be true to yourself.)

In a low black bowl the teacher places a corn plant leaf at a forty-five degree angle and positions a dracaena leaf and freesia blossom next to the corn leaf, making sure there are no gaps between stems in order to achieve the illusion of oneness. To show variety, she de-thorns and prunes a quince branch, and replaces the corn plant leaf with this new material while explaining the principles of sai no hana—an ecological style of flower arrangement for the twenty-first century that uses fewer flowers to create simple, elegant lines. Her actions are confident; her movements easy and graceful. In a matter of minutes, she has achieved an asymmetrically balanced arrangement that conveys a feeling of serenity and inner harmony. In gazing at such an arrangement, the viewer is reminded of the Shingon teaching that artistic creations are Buddhas in their own right; that nature, art, and religion are one; and that all persons are intrinsically enlightened but live in a state of delusion until awakened.

The teacher continues to write the twenty-eight prohibitions on the board while the students take copious notes.

- Don’t arrange flowers so that they cover each other. (Each flower, like each person, should shine with individual uniqueness.)

- Don’t make an arrangement that looks like an arrow going toward your guest. (This suggests violence and goes against the principle of harmony.)

- Don’t use stems having the same width, instead, think of them as strings of a samisen (Japanese balalaika). (Different widths produce a variety of tones, an aura of complexity.)

- Flowers should not face the viewer like a mirror. (This implies narcissism and lack of humility.)

- Don’t have two leaves be directly opposite each other. Prune one or the other. (Avoid competition, as it can turn into a battle.)

- Don’t place flowers as if they are holding each other. (Stand on your own, strong and independent.)

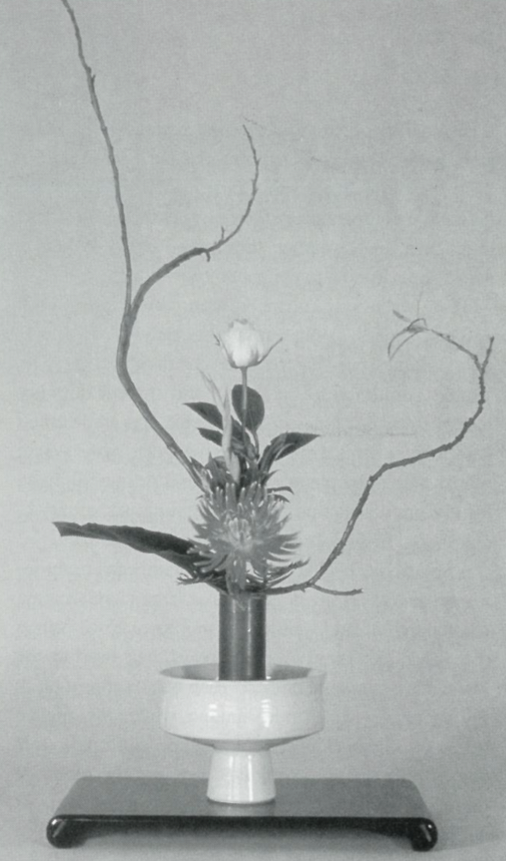

Once these rules are established the class turns to the task of morimono, one of the five variations under the Bunjinka.Bunjin means “cultured person” and comes from Bunjinga, a Chinese drawing school introduced to Japan in the eighteenth century. Bunjinka incorporates freedom of composition and playfulness of design while still maintaining the artistic principles of balance and harmony. Arrangements in this style are given titles taken either from the symbolic meaning of the flowers—pine as eternal youth, rose as everlasting spring—or from old Chinese folk tales and poems. To create morimono arrangements, dai (wood or bamboo platforms) are fetched from an ancient storeroom built with wood beams as thick as tree trunks and lined with heavy shelves sagging with the weight of hand-built ceramic containers.

On the rectangle dai (square shapes are considered uninteresting—too symmetrical), students place a Japanese pumpkin off to one side, consider the color combinations, stack carrots, peppers, and mushrooms in asymmetrical configurations, and are reminded that groups of three and five are better than fours and sixes, although two is okay. Bitter is good with sweet; green is good with red—all part of achieving yin and yang, the balance of opposites that makes a harmonious whole.

The final ikebana lesson goes back to the religious roots of the Saga school and the six elements of Shingon Buddhism: earth, water, wind, fire, space, and knowledge. Symbolically, these six elements embody aspects of Buddha-nature, each one perfect unto itself but not existing apart from the whole. Earth depicts mountains and prairies, but also bones and muscles; water represents oceans and rivers, but also blood and tears; fire is at once sunshine and body heat; wind symbolizes breath.

Many kinds of materials can be used in the shogonka style, but for this lesson the teacher uses long sweeping willow branches for fire and water, a pruned azalea branch for wind, leathery ferns for earth, pink amaryllis for space, and yellow lilies with cedar for knowledge. The colors create harmony; the six elements work as a dynamic unit; the whole radiates oneness of body and mind. To engage in the creation of a shogonka arrangement is to contemplate the body of Buddha through the metaphor of nature. Once the arrangements are complete, they are placed in viewing alcoves to be contemplated as spiritually inspired art by anyone passing by.

Joan D. Stamm lived in Japan from 1991 to 1993. “Buddha Nature and Ikebana” was first published in Seeing Through Symbols, Chrysalis Reader No. 5, pp. 85-89 (Swedenborg Foundation, West Chester, Pennsylvania, 1998), and is reprinted by permission of the publisher.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.