In a perhaps apocryphal tale, the painter Ito Jakuchu (1716–1800) once came across live sparrows for sale in Kyoto’s Nishiki Market. Taking pity on the birds, as they were “fated to roast on a spit,” he bought a large number of them and released them into his garden. According to the Rinzai Zen monk Daiten Kenjo, a friend and mentor to Jakuchu, this expression of pity “was the compassion of one destined to become a bodhisattva.”

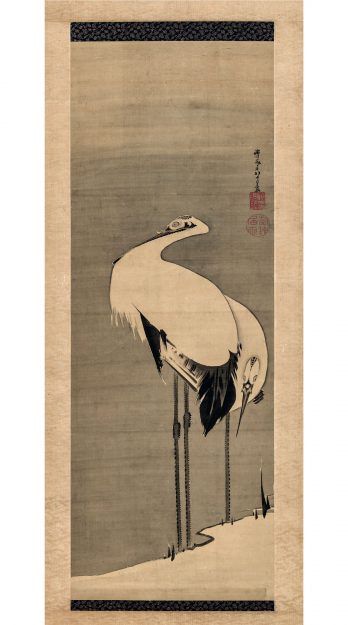

Jakuchu brought this same spirit of compassion to his artistic work, directing a careful attentiveness toward ordinary creatures often considered too humble for traditional Japanese painting. A devoted lay practitioner, or koji, he maintained close friendships with Zen monks throughout his life, and his Buddhist practice provided a framework for his art. His name, likely given to him by Daiten, translates to “like a void” and was taken from a phrase from the Tao Te Ching, “The greatest fullness is like a void.” Jakuchu’s work indeed demonstrates the fullness and vibrancy of life that close observation reveals, and his technical precision and almost obsessive attention to detail give his paintings a vivid realism that sometimes borders on the surreal.

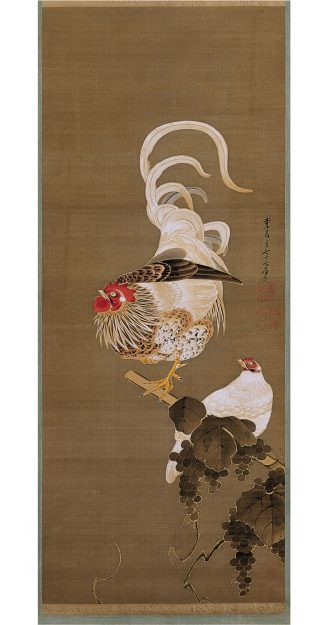

The eldest son of a Kyoto greengrocer, Jakuchu spent much of his youth in the bustling Nishiki Market among the stands of vegetables and fish. As a teenager, he trained in classical painting under Ooka Shunboku, a minor master in the Kano school known for his bird-and-flower paintings; however, Jakuchu ultimately found this school too strict and opted instead to learn to paint through studying elements of his daily life, from the vegetables in his father’s shop to the fish in the market to the assortment of roosters and fowl he raised at home. In fact, he sometimes imported exotic birds into his garden so that he could observe them firsthand and render them with appropriate vivacity and character.

Jakuchu’s work demonstrates the fullness and vibrancy of life that close observation reveals.

After his father’s sudden death in 1739, Jakuchu took over the family shop; however, he had little interest in business and often sought refuge from the bustle of the market by retreating to the mountains. According to Daiten, Jakuchu “was quite oblivious to the luxurious attractions that daily seduce one’s eyes and ears in cities and towns” and was instead “inclined to enjoy solitary pursuits, patiently labor[ing] day by day to develop his talents and expressive means.” To this end, he built himself a studio on the outskirts of Kyoto, which he called Shin’en-kan, or “Villa of the Detached Heart,” pulling a line from the 4th-century Chinese poet Tao Qian.

Around this time, Jakuchu first met Daiten, the Rinzai monk-poet who came to be his religious mentor, close friend, and artistic patron. In addition to providing spiritual guidance, Daiten introduced Jakuchu into literary circles—and gave him access to the extensive archive of classical Japanese and Chinese artwork housed in Kyoto’s Shokoku-ji temple. Jakuchu honed his technique through assiduous study of these paintings, as well as European books on botany, zoology, and mineralogy.

At the age of 40, Jakuchu retired from the family business, passing ownership to his younger brother. Free to pursue painting, he moved to Shokoku-ji and embarked on his most famous work, Doshoku Sai-e, or Colorful Realm of Living Beings. Now designated as a National Treasure, Colorful Realm consists of thirty-three scrolls of animals, plants, insects, and fish, with a triptych of Shakyamuni Buddha and the bodhisattvas Manjushri and Samantabhadra as its centerpiece. A visual menagerie of flora and fauna, the series depicts more than one hundred species of animals rendered in brilliant color and exquisite detail, among them twenty-five varieties of birds, seventy types of insects, and 146 different kinds of seashells. The resulting compositions are dizzying and at times hypnotic, imbuing the everyday with an almost otherworldly vitality. The Zen monk Baisao was so moved by the series that he gifted Jakuchu a hanging scroll that read, “Enlivened by his hand, his paintings are filled with a mysterious spirit.”

Upon its completion, Jakuchu donated Colorful Realm to Shokoku-ji in 1765 in the hope that it would be used for rituals and ceremonies—and that his work would in some way contribute to the temple’s merit. “On a daily basis I devote myself heart and soul to painting, drawing superlative flowers and trees, and attempting to capture the true forms of birds and insects,” he wrote in the series’s dedication. “My aim is not to win fame or glory in the mundane world but to contribute to the sacred accoutrements that adorn the temple.”

Jakuchu’s attentiveness and devotion to the details of daily life allowed him to portray the character of each creature with great humor and theatricality, from his beloved strutting roosters to quizzical cockatoos. He took this personification a step further with Vegetable Parinirvana, a monochrome ink-brush painting depicting the Buddha’s entrance into nirvana using more than sixty varieties of produce. A daikon radish reclines at the center of the scroll as the dying Buddha, surrounded by mourning eggplants, cucumbers, and yams; Queen Maya, the Buddha’s mother, looks on from Tavatimsa Heaven as a quince. The painting has been understood as a testament to the buddhanature inherent in all beings, even radishes.

“Enlivened by his hand, his paintings are filled with a mysterious spirit.”

As he grew older, Jakuchu became more absorbed in Zen Buddhism and began spending more of his time at the Obaku Zen temples in the mountains south of Kyoto. There, he developed close relationships with the Obaku monks and turned to a quieter minimalism, putting aside the bold polychromatic scrolls of Colorful Realms for monochrome ink. His projects also took on more explicitly Buddhist themes, and he began work on a large-scale sculpture garden at Sekiho-ji called Five Hundred Arhats, depicting the eight phases of the Buddha’s life through expressive stone statues.

In 1788, Jakuchu’s studio was destroyed in the Great Tenmei Fire, along with his family’s shop and many of his paintings. Over the course of the next few years, he became increasingly reclusive, eventually taking up residence at Sekiho-ji so he could continue to work on the sculpture garden. Facing financial ruin from the fire, Jakuchu funded the project by selling ink paintings to local villagers in exchange for bushels of rice, which he then traded for silver to pay the stonemasons. Inspired by Baisao, or “The Old Tea Seller,” he styled himself as Beito-o, or “The Old Man of One Rice Bushel.”

Jakuchu continued to work on the garden until his death at the age of 84. After he died, it fell into disrepair as sculptures were stolen, buried by earthquakes, or eroded by time; though at its height it boasted more than a thousand statues of the Buddha and his followers, now only 420 remain. Still, Jakuchu leaves behind an impressive collection of silk scrolls, screens, and ink paintings that illustrate the richness and exuberance of everyday life—if only we learn how to look.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.