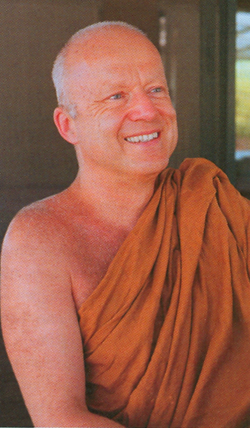

Since 1970, The Buddhist Religion has introduced countless students and practitioners to the history of Buddhism. Readers of the fifth edition, published in July, are in for some surprises: juicy new material on early Indian Buddhism and on the development of the Mahayana tradition, plus a new title, Buddhist Religions, which expresses the notion that Buddhism is not a single religion, as long presumed, but a family of religions with distinct institutions, practices, and views. For background on these changes, Tricycle spoke with Thanissaro Bhikkhu, abbot of the Metta Forest Monastery, in California, and one of the authors of the new edition (along with Willard L. Johnson, of San Diego State University and the late Richard H. Robinson, of the University of Wisconsin).

Why a new edition? Two reasons. We’ve got new evidence—new texts, new documents, new archaeological findings we didn’t have ten or fifteen years ago—that has changed our understanding of early Buddhism. Then, too, people are asking new questions: Why are we studying the history of Buddhist religions? What is meaningful in this story? There’s a point at which new evidence doesn’t change the picture, it breaks the frame.

Why a new edition? Two reasons. We’ve got new evidence—new texts, new documents, new archaeological findings we didn’t have ten or fifteen years ago—that has changed our understanding of early Buddhism. Then, too, people are asking new questions: Why are we studying the history of Buddhist religions? What is meaningful in this story? There’s a point at which new evidence doesn’t change the picture, it breaks the frame.

What are the discoveries that have broken the frame? Among the most interesting rediscoveries are some very early texts known as the avadanas [lessons]. These are stories about how the Buddha and famous arhats [those who have attained the penultimate stage of awakening] got started on the path many aeons ago. Like the jatakas [tales of the Buddha’s past lives], the stories are aimed at inspiring a sense of devotion. A lot of these texts were written when the stupa cult was becoming popular in India. They were advocating the idea that in order to get started on the path one needs to have the merit field of the Buddha. By performing services to the Buddha or his relics, you plant the seeds of merit that will eventually result in awakening.

The avadanas changed my understanding of some the rituals and ceremonies I experienced as a monk in Thailand. Until the rediscovery of the avadanas, it was assumed that popular devotional Buddhism as practiced in Southeast Asia today was a corrupted form. But looking at the avadanas you see that the practices are in fact very old.

These texts, with their emphasis on Buddha-fields and vows for awakening, also provide the missing link between the early canons and the Mahayana, thereby rewriting the story of how the Mahayana arose.

Why is it important for practitioners to know the history of Buddhism? It gives you a sense of where the practice is coming from. You begin to see the context, to see which parts of the teachings and rituals are universal and which are culturally derived. At the same time, you become more aware of the unexamined assumptions underlying your own practice.

In the West, we think we have a right to reform anything that doesn’t fit in with our values. But the question is, are you coming to the dharma to change the dharma in line with what you already believe, or are you willing to set your presuppositions aside and let yourself be changed by the dharma? Buddhism hasn’t changed itself over time. Instead, it has been changed by the people who encountered it. This means we have to be careful how we change it: Are we keeping the doors to awakening open, or are we closing them? Are we helping with the cure for suffering, or standing in the way?

Why the title change from The Buddhist Religion to Buddhist Religions? The title change reflects the notion that Buddhism isn’t one religion but a family of religions. As in any family, there’s a common gene pool on which they draw, but what they fashion from those genes may be very different structurally.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.