Thus have I heard:

The army ordered

All Japanese faces to be evacuated

From the city of Los Angeles.

This homeless monk has nothing but a Japanese face. He stayed here thirteen springs

Meditating with all faces

From all parts of the world,

And studied the teaching of Buddha with them. Wherever he goes, he may form other groups Inviting friends of all faces,

Beckoning them with the empty hands of Zen.—Nyogen Senzaki, “Parting,” May 7, 1942

The story of America has long been cast as one of westward exploration and expansion, beginning with settlers from Europe who crossed the Atlantic Ocean to the New World, and radiating out from initial outposts on the Atlantic Coast across the plains of the Midwest to the Pacific Coast and beyond. As the 19th-century doctrines of manifest destiny and American expansionism make clear, claiming territories to accommodate the ever-increasing populations of immigrants from Europe was justified in terms of both culture and religion; the United States was described as uniquely destined and divinely ordained to take on the role of a “civilizing influence” that would spread Anglo-Protestant values into lands supposedly empty of civilization. Implicit in this view of history has been the idea that America is, at its base, a Christian nation.

But what happens when we flip the map? For the hundreds of thousands of Asian immigrants who crossed the Pacific to reach America in the 19th and early 20th centuries, the American West was the Pacific East. Their American story has an eastward trajectory—one that begins in the mid-1800s on the sugar plantations of Hawaii and moves through California and the Pacific Northwest and eventually toward the Atlantic Coast.

American Buddhism thus begins with the migration of Asians who brought the teachings, practices, and institutions of a 2,500-year-old religion across the Pacific. These immigrants saw in America the promise of a country that could provide not only a source of livelihood but also the right to freely practice their own religious beliefs. In this, they were putting their faith in one of the central tenets of the United States Constitution: the First Amendment, which, agreed upon and ratified by the Fathers, guarantees religious freedom.

So which is it? Is America best defined as a fundamentally white and Christian nation? Or is it a land of multiple races and ethnicities and a haven for religious freedom? More pointedly—does the fact of being nonwhite and non-Christian make one less American?

Never has this question been asked with more urgency and consequence than it was in the time of the mass incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II. War, with its reflexive interrogation of who can be trusted and who cannot, who belongs and who is the enemy, often brings to the surface the deepest questioning of a nation’s identity. In the wake of the Pearl Harbor attack, the question whether persons of Japanese ancestry would remain loyal to the United States became the subject of considerable debate among government and military officials, the media, and the general public. At stake were issues of both morality and law—two-thirds of the Japanese American population were American citizens and thus presumed to have constitutionally guaranteed rights of equal protection, due process, and religious freedom. But could they be trusted? Within months, debate was brought to a swift and irrevocable conclusion when, on February 19, 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed into law Executive Order 9066. This gave the military discretion to do whatever it deemed necessary to secure the safety and security of the United States. Pursuant to it, the Army removed all persons of Japanese ancestry—more than 110,000 men, women, and children—from the west coast and put them in camps surrounded by barbed wire and guard towers. Anyone with even a drop of Japanese blood was rounded up and incarcerated.

Does the fact of being nonwhite and non-Christian make one less American?

Marked as they are by ethnic, racial, and cultural differences from the majority European-origin population of the United States, Asian immigrants have long faced such nativist prejudices. Starting with the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, which erected a symbolic wall on the Pacific to keep out the so-called “heathen Chinee,” and continuing on through various laws that banned Asian immigrants from naturalizing as citizens, owning land, or marrying white Americans, decades of legal and social structures of exclusion anticipated what happened to the Japanese Americans after Pearl Harbor.

But while it has become commonplace to view their wartime incarceration through the prism of race, the role that religion played in the evaluation of whether or not they could be considered fully American—and, indeed, the rationale for the legal exclusion of Asian immigrants before that—is no less significant. Their racial designation and national origin made it impossible for Japanese Americans to elide into whiteness. But the vast majority of them were also Buddhists; in fact, Japanese Americans constituted the largest group of Buddhists in the United States at the time. The Asian origins of their religious faith meant that their place in America could not be easily captured by the notion of a Christian nation. Religious difference acted as a multiplier of suspiciousness, making it even more difficult for Japanese Americans to be perceived as anything other than perpetually foreign and potentially dangerous.

People of Japanese ancestry were thus deemed to be a threat to national security and incarcerated indiscriminately and en masse, something that did not happen to Americans of German and Italian heritage, despite the fact that the United States was also at war with Germany and Italy.

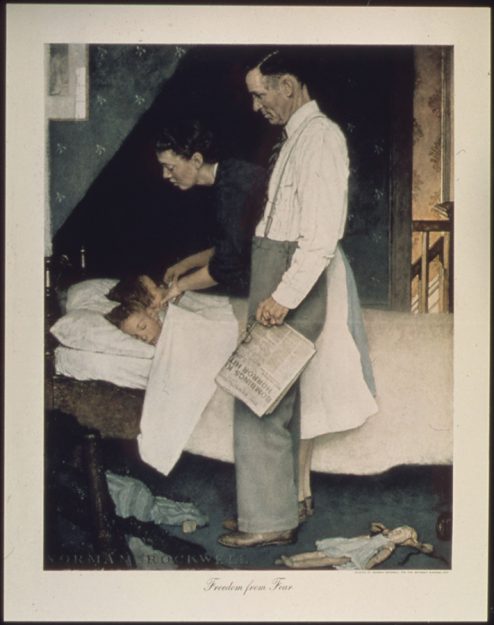

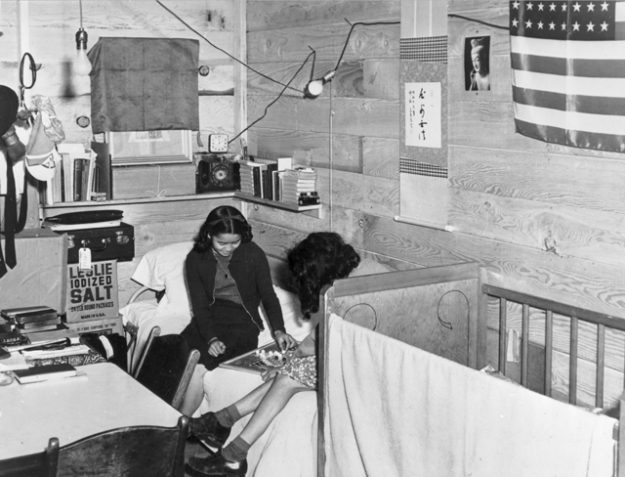

Doubly excluded from whiteness and Christendom, Japanese American Buddhists during World War II represent a particularly poignant object lesson about the perceived boundaries of who can claim the rights of being American. Their insistence on maintaining their Buddhist practices and beliefs despite imprisonment—using the searchlights from guard towers to focus their meditation practice, building Buddhist altars for their barracks rooms out of wood scavenged from the desert, or insisting that space be made available for them to congregate and worship as Buddhists—constitutes one of the most inspiring assertions of religious freedom and civil liberties in American history. Thus, this is a story about America.

But the wartime experience of Japanese American Buddhists is also a story about Buddhism in America: how the roots of what is now a popularly accepted religion were forged in the crucible of war by a community that strove to remain grounded in tradition while also adapting to the multisectarian, multigenerational, and multiethnic realities of Buddhist life in the United States.

Given how thoroughly Japanese American Buddhists have been excluded from the narrative of American belonging, it is perhaps not surprising that their stories are not readily found in most histories of that time. In my own research, I have learned much from accounts by Japanese American Buddhists themselves, drawing from sources such as previously untranslated diaries and letters written in Japanese, dozens of new oral histories, and the ephemera of camp newsletters and religious service programs. These allow a telling of the story from the inside out, and make it possible for us to understand how the faith of these Buddhists gave them purpose and meaning at a time of loss, uncertainty, dislocation, and deep questioning of their place in the world.

To understand how something called American Buddhism came to exist, we must look to the people who embodied the teachings, even during wartime exclusion.

The insights found in Buddhist scripture cannot be transmitted without people to actualize them. To understand how something called American Buddhism came to exist and persist, we must look to the people who embodied the teachings of the Buddha even during wartime exclusion. Among those who exemplified this struggle to find a place for themselves and their religion in America was the Zen Buddhist priest Nyogen Senzaki.

By the time Senzaki penned the poem “Parting,” which opens this essay, in May of 1942, he had already been in the United States for close to four decades. But six months earlier, everything had changed when Japanese naval planes attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. A day later, his adopted country had declared war on his native country, and most of his fellow Buddhist priests had been rounded up and imprisoned, some of them before the smoke had cleared at Pearl Harbor.

Senzaki stands out because although he had trained in the traditional Buddhist monasteries of Japan, he had made it his life’s work to translate Buddhism into teachings that would be meaningful to his fellow Japanese immigrants and their English-speaking, American-born children, as well as to non-Japanese American converts.

Born in 1876, Senzaki was rescued by a Japanese Buddhist priest from the edge of a frozen riverbank where his mother had died giving birth. He was adopted into a Buddhist temple family and eventually ordained as a novice priest. His Zen teacher, Soyen Shaku, became the first Japanese Zen priest to visit the United States, invited in 1893 to represent Buddhism at the World Parliament of Religions in Chicago. A dozen years later, with barely any English, the 29-year-old Senzaki followed his teacher’s example and arrived in America. Frustrated by the rigidity of Buddhism in Japan, he had decided to cross the Pacific in the hopes of finding a new path forward for the religion in the land he had read about as a teenager in Benjamin Franklin’s autobiography. “See whether it conquers you or you conquer it,” his Zen master had told the young priest as he prepared for his new life in California.

After landing in San Francisco, Senzaki studied the works of Ralph Waldo Emerson and William James in the public library while working at menial jobs. He then moved to Los Angeles, where, over the course of “thirteen springs,” he succeeded in building up a vibrant Buddhist community consisting of Japanese immigrants and converts from a variety of ethnic backgrounds—“Meditating with all faces / From all parts of the world,” as he writes in the poem. He saw in the American outlook an openness that might potentially welcome the teachings of Buddhism.

This optimism was tested but not broken by the US Army’s order for “all persons of Japanese ancestry” to assemble for immediate removal from the Pacific Coast. “Parting,” written on the eve of his departure from the community he had worked so hard to build, is not only a Buddhist commentary upon the US government’s incarceration process, it is also a Buddhist teaching he was leaving behind for those in a home to which he might not be able to return. Addressing the Los Angeles Zen community, he begins the poem with the classic opening words for a sutra, a text said to represent the Buddha’s own teaching: “Thus have I heard.” This phrase is a way of representing Buddhist scriptures as an authentic transmission of religious guidance that could enable the Buddha to be ever present.

“Parting” employs this classic preamble at a traumatic moment for Buddhists, as a way to give inspiration amid the hardships of the American present. “The army ordered / All Japanese faces to be evacuated,” his poem recounts. “This homeless monk has nothing but a Japanese face.” As someone who had experienced dislocation a number of times before finding a home in Los Angeles, Senzaki calmly accepted this new forcible migration. But while the poem serves as a chronicle of his experiences, it is also deeply imbued with Buddhist resonances and his identity as a Zen priest. Upon ordination, Senzaki had dedicated himself to the Buddhist path; a journey that is traditionally termed “leaving home.” As a “homeless monk,” Senzaki was guided not by the comforts of social convention but by an understanding that nowhere and everywhere can be a home in which to practice Buddhism. Yet despite the exigencies of war and facing an unknown period of incarceration, he asserts the possibility of a place for Buddhism in the United States, noting that “Wherever he goes, he may / form other groups / Inviting friends of all faces, / Beckoning them with the empty hands of Zen.” For Senzaki, the act of continuing the practice of Buddhism, even under incarceration, was to serve as witness to the realities of the present moment and make the teachings of the Buddha come alive in it.

Senzaki believed that the powers of ultimate truths, spiritual practices, and ethical acts could be activated only when religious teachings were able to escape their hermetically sealed texts and engage with the existential struggles of life. In this view, the reinscription of scripture in a contemporary idiom is a potent act of religious imagination that gives life purpose and meaning. It is by reflecting on his forcible relocation that Senzaki is thus given the chance to write a Buddhist scripture—an American sutra—inspired by the terrible circumstances of his times.

After being deported from Los Angeles, Senzaki initially spent several months in temporary quarters just east of Los Angeles. The War Relocation Authority (WRA) had not yet finished construction of the ten incarceration camps that were to be used for the duration of the war. While those were being built, Senzaki, along with roughly eighteen thousand other people of Japanese ancestry, had been sent to the Santa Anita Racetrack, where they were forced to live in hastily converted horse stalls. Upon hearing that he would be moving again—this time to the now-completed WRA camp in Wyoming called Heart Mountain— Senzaki wrote another poem, entitled “Leaving Santa Anita”:

This morning, the winding train, like a big black snake

Takes us as far as Wyoming.

The current of Buddhist thought always runs eastward.

This policy may support the tendency of the teaching.

Who knows?

By writing that the “current of Buddhist thought always runs eastward,” Senzaki is evoking ideas that originate with the Buddha’s prophecy that, after he died, his teachings—the dharma—would inevitably be transmitted eastward. In the traditional formulation of Buddhism’s eastward advance (bukkyo tozen), at least as it is described in Japan, the spread of the religion begins in India, then moves to China and Korea before finding an endpoint in the islands of Japan. But by the late 19th century and early 20th century, some Buddhists who were migrating to the Americas had begun to think of their journey as a further extension of this eastward trajectory.

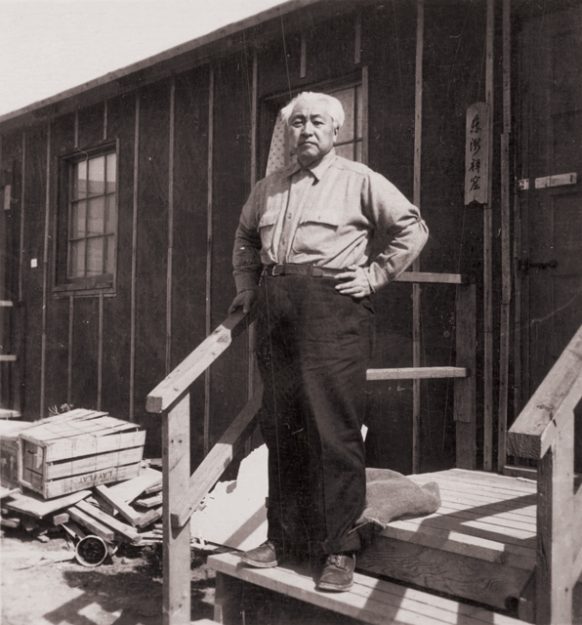

Indeed, once Senzaki arrived at the Wyoming camp, he went so far as to call his makeshift barracks the Tozen Zenkutsu—The Meditation Hall of the Eastbound Teaching. Far from giving up on his faith, Senzaki designated his new home as a Zen meditation hall; a new locus for American Buddhism. Confronted with unthinkable hardships, Senzaki and other Buddhists found that they would have to draw upon the deepest currents of Buddhist thought in order to persist and endure. In this, they were laying claim to the belief that, regardless of circumstance, Buddhism could not only survive but indeed flourish in the United States.

Were it not for Senzaki’s Buddhist teachings, which inspired efforts by postwar Zen adherents to preserve the sermons, letters, and miscellany of their teacher whose perspective they valued so highly, it is likely that this contemporaneous record of a Buddhist perspective on the wartime incarceration would simply have disappeared.

Likewise, the diaries, letters, and other fragments of memories about the wartime experience could easily have been relegated to the ash heap of history. But, like the Buddhism they describe, they have endured. In acts large and small, they were preserved by individuals and families who somehow sensed that there was something inherently valuable—and indelible—in the Buddhism that they had been born into or had brought with them.

Confronted with unthinkable hardships, Senzaki would have to draw upon the deepest currents of Buddhist thought in order to persist and endure.

I came upon two such accounts in 2000, shortly after the death of my graduate school advisor, Professor Masatoshi Nagatomi, when his widow asked me to help sort out his papers. For over forty years, starting in 1958 when he joined the faculty at Harvard University as an instructor in Sanskrit and later as the university’s first professor of Buddhist studies, Nagatomi had mentored generations of scholars of Indo-Tibetan and Sino-Japanese Buddhism, many of whom ended up teaching at leading American universities. I was one of his last students.

His files were, needless to say, voluminous. But buried in his great mass of papers—mixed with dissertation chapter drafts and letters from journals— was a handwritten Japanese document with the name Nagatomi written on it, though not in my professor’s familiar script. After a few days, I realized I had come across personal notes penned by Professor Nagatomi’s father, Shinjo Nagatomi. Though Professor Nagatomi rarely spoke about it, his father had done pioneering work as a Buddhist priest, first in Canada and then in the United States. The notes I found among my professor’s papers included a journal and drafts of sermons Shinjo Nagatomi had delivered in the tar paper barrack that had served as his Buddhist temple in the Manzanar camp in eastern California.

Upon request from Professor Nagatomi’s widow, Masumi Nagatomi, I spot-translated several selections of the notes. One of them urged the elderly to persevere, despite the loss of their homes, livelihoods, and everything they had worked for as immigrants to the United States. Another exhorted young Japanese Americans to be law-abiding Buddhists loyal to their country, despite the war with their ancestral homeland.

As I learned from Mrs. Nagatomi, at the time of the attack on Pearl Harbor, Masatoshi Nagatomi was fifteen years old and living with relatives in rural Yamaguchi Prefecture, having traveled there without his mother, father, and siblings, who remained home in San Francisco. With the outbreak of hostilities, he found himself unable to return to the United States, and spent the remainder of the war stuck in Japan, where his only news of his parents and sisters would come from the rare International Red Cross letters his father sent him from behind barbed wire.

Conscripted to the shipyards of the port city of Kobe, Masatoshi Nagatomi struggled with others there to survive horrific working conditions and ever-diminishing food rations. Granted a brief leave to visit his relatives, he found himself on a train packed with weary and wounded soldiers that passed through the city of Hiroshima on August 6, 1945, the day it was bombed. Ordered to close the window blinds, Nagatomi could only peek at the devastation. Amid the chaos of the final days of the war, he resolved to rejoin his family in America as soon as he could.

As Mrs. Nagatomi told me her husband’s story, her own wartime story began to emerge. Masumi Kimura (her maiden name) was 10 years old and living with her parents in Madera, California, when the Japanese planes attacked Pearl Harbor. More than sixty years later, she still vividly recalled the tension and fear that gripped her family and hometown that December day. Word had quickly spread that all the Buddhist priests at the nearby Fresno Buddhist Temple, a temple of the Jodo Shin tradition, had been arrested, and white teenagers had shot up the temple’s front door. The board president of the Madera Temple, also Jodo Shin, had also been apprehended by the FBI, a matter of great concern for Masumi’s father, who was a prominent board member of the rural temple. Like many residents of the small farming community in California’s Central Valley, her parents were issei—first-generation Japanese Americans—and Buddhists.

In the wake of Pearl Harbor, in a climate of growing suspicion and hostility toward Japanese Americans, Masumi’s father decided to take steps to prove the family’s loyalty to America. One day, Masumi was performing her daily chore of lighting the furnace next to their Japanese-style bathtub when her father entered the room. He was carrying items he had found throughout the house that had Japanese-language inscriptions or “Made in Japan” written on them. Among them were Masumi’s precious Hinamatsuri dolls. As tears rolled down her cheeks, she watched him throw the dolls and all the other Japanese artifacts into the fire.

Her father did not burn everything, however. He could not bring himself to destroy the bound edition of Buddhist sutras that had been handed down through generations of the family. Instead, he asked his wife to find boxes and some Japanese kimono cloth while he went outside and dug a hole behind their garage with a backhoe. After wrapping the Buddhist scriptures and the minutes of board meetings from the Madera Buddhist Temple in the kimono cloth, he placed them in tin rice-cracker boxes, carefully lowered them into the hole, and covered them with dirt. By burying them next to the garage, he hoped to be able to find and recover them at some later date.

Shortly thereafter, in April 1942, the Kimuras were ordered to report to the Fresno Assembly Center, which had been set up at the local county fairgrounds. They ended up having to sell their farm to their neighbors for less than one-twentieth of its market value, and, after depositing a single suitcase of their most valued remaining possessions at the Fresno Buddhist Temple for safekeeping, they arrived at the center, where they were quartered in a horse stable designated Barrack E-17-2. They were, however, more fortunate than the majority of Japanese Americans. Instead of being transferred to one of the more permanent WRA incarceration camps, the Kimuras were among the handful of families approved to join work programs east of the military zone, in Utah, where they worked as cheap farm labor for the duration of the war.

After the war ended, the Kimura family returned to Madera in the hopes that they would be able to buy their farm back. But the new owners demanded a sum ten times greater than what the Kimuras had accepted for the farm three years earlier. They had also torn down the garage, making it impossible for the Kimuras to find the precious belongings they had buried near it. Their single suitcase of valuables, which had been stored away for safekeeping, had been lost as well when vandals ransacked the Fresno Buddhist Temple during the war. Unable to raise the money to buy back the farm, the Kimuras went to live with relatives in Los Angeles.

This story, told to me in the gardens of my advisor’s widow in Cambridge, Massachusetts, has stayed with me over the years. Though just one among tens of thousands of stories of Japanese American Buddhist families during World War II, it encapsulates both the loss and the hope that made possible the birth of an American form of Buddhism. Though the Kimuras were willing to let go of their Japanese national identity by burning objects symbolically linked to Japan, the one thing they refused to erase was their Buddhist faith. Indeed, they ended up quite literally placing Buddhism into the soil of America for safekeeping. Like those of Senzaki and many others, their actions demonstrated their firm conviction that their adopted homeland would one day be a place where their faith could grow and flourish.

The Buddha taught that identity is neither permanent nor disconnected from the realities of other identities. From this vantage point, America is a nation that is always dynamically evolving—a nation of becoming, its composition and character constantly transformed by migrations from many corners of the world, its promise made manifest not by an assertion of a singular or supremacist racial and religious identity, but by the recognition of the interconnected realities of a complex of peoples, cultures, and religions that enrich everyone.

The long-ignored stories of Japanese American Buddhists attempting to build a free America—not a Christian nation, but one of religious freedom—do not contain final answers, but they do teach us something about the dynamics of becoming: what it means to become American—and Buddhist— as part of an interconnected and dynamically shifting world.

These stories, like Senzaki’s poem, constitute an American sutra.

Thus have I heard.

♦

Adapted from American Sutra: A Story of Faith and Freedom in the Second World War, by Duncan Ryuken Williams © 2019. Printed with permission of Harvard University Press.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.