MY DAUGHTER HAS BEEN LOST TO ME in a world I don’t understand. I have been lost to her in a world she came to scorn. In more than two years, I haven’t spoken with her. Now, woken up by the telephone’s beeping, I hear Veronica’s voice, sure, cool, coming through the receiver from a great distance.

“And don’t worry about your Hindi, Mummy. It’s easier than Spanish. I’ll meet you twenty days from now in New Delhi. At the airport.”

I watch the ceiling’s shifting ladders of reflected light cast from the night traffic moving south on Fifth Avenue, their verticals scored with flickering ribbons the color of ripe pomegranate juice and the bottled grenadine syrup Veronica liked to sip for its color suggestive both of myth and mercurochrome. My heart beats like a drum.

“Where are you?”

“I’m in a toasty hot telephone booth in Janpath. If I call collect, I don’t have to wait long. What time is it in New York?”

“Almost four in the morning. Tuesday.”

I hear the echo of my voice saying, “To you’s day.”

Her childlike laughter is an unexpected gift. “It’s afternoon here. A month from now I’ve arranged an audience for you in Dharamsala with His Holiness.”

“The Dalai Lama?”

“Yes. I thought you’d like to write about him. I gave him some of the flea medallions you sent for his Lhasa apso.”

“But what should I say? What should I ask him?” I reach for my notebook and blue felt-tipped pen.

“You can ask His Holiness anything. He’s very wise about everything, Mummy.”

“Well, I’m not.”

Coils of inadequacy spiral around me and squeeze all relevant intelligence from my mind. I remember, years ago, hugging Veronica when she had a garter snake hidden and snuggled beneath her T-shirt. The snake wriggled. I shrieked, jumped back. Veronica laughed and crowed, “Silly Mummy. Frightened Mummy. You’re such fun to scare!”

The mind’s time is faster than ordinary time. Now she says, “Sorry. I thought you’d be pleased if I fixed it all up for you.” From fourteen thousand miles away, I hear Veronica sigh. Impatience. Disappointment. Reproach.

“It isn’t important whether you believe His Holiness to be an embodiment of compassion, Mummy,” Veronica goes on. “At least you could appreciate the purity of his friendliness, his benevolence and tensionlessness. It could benefit your mind. The Indians call it ‘darshan.'”

“Darshan?”

“Yes, darshan. It’s what happens to you when you visit enlightened people and you receive from them a sort of psychic transmission that the English word ‘blessing’ doesn’t really convey, although it could, if you wanted it to.”

“Darshan,” I hear my overly eager need-to-please voice chirping, “Oh, yes, yes! You wrote me about that!”

For a moment, my daughter and I are silent. Then, dispensing with that part of me which ought to be up to her intelligence and isn’t, Veronica gentles her voice to the persuasive and assured sweetness of one asking for a favor certain to be granted. “Could you possibly bring a few things with you when you come? Sweaters, a dress, things like that? And those yummy dried soups and the very dark kind of Swiss chocolate? And some Mediterranean herbs? You don’t have to bring them in jars or tins. You can empty them into those plastic things. You know, Baggies.”

“Baggies. Yes.”

No darshan about plastic. In my mind I am haring about decanting thyme, basil, oregano, and tarragon into little sacks, firmly securing their fragrance with elastic bands. Staples might tear and make holes.

“There’s no way to make a bouquet garni around Dharamsala,” Veronica says silkily. “My thumb and index finger have taken on an almost permanently green tinge from pinching leaves and holding them to my nose. There’s wild basil in Manali but not in Dharamsala….And I need some of those fine accountant pens to draw with,” Veronica persists. “And cognac. Remy Martin? Even in Bombay and Delhi, you can’t get decent cognac.” I feel suddenly lifted with the sense of being needed.

“Of course, my darling Elsa Cloud. Is there anything else I can bring?”

When Veronica was sixteen, she said, “I’d like to be the sea, the jungle, or else a cloud.” The last three words, transformed homonymically to Elsa Cloud, became my endearment for her. Darling Elsa Cloud. When I was twenty-five—the same age Veronica is now—I traveled to India to discover India for myself and, by writing about it, to make it my own. I saw Bombay and Delhi with Kipling’s Kim, an all-knowing interlocutor at my side. I went to Nagpur and ate its sweet oranges while I watched the dances of an aboriginal tribe that lives in its province. I saw Ellora and Ajanta, the Elephanta Caves and country villages in the company of Mulk Raj Anand, a distinguished Indian novelist and art scholar who always wore something red, which was for him the color of life. He described and regaled me with stories of the great blue, fluteplaying god Krishna and his bevy of amorous gopis (cowherd maidens). I saw India through what felt like a rape of all my senses in a tumultuous assault of sight and sound and smell and taste and resonating color.

Veronica is experiencing India with a Tibetan lama named Geshe-la, meditating, practicing Buddhism, studying Tibetan grammar in a lamas’ college in Dehra Dun, living “at the end of a goat path in the Himalayas” in a three-storied house she rents for an infinitesimal monthly sum. Cows are stabled on the ground floor. Corn and hay are stored on the top floor. Her bed is in arm’s reach of a cylindrical woodburning stove or tandoor, “warm and cozy,” which in her drawing of it has the look of a pure, clean sculpture, with two removable lids on top where she can put pots for cooking and for heating the water that she fetches in a bucket from a nearby stream. She writes that Buddha’s answer to life’s riddles is the Four Noble Truths. Suffering exists. Suffering is caused by desire. Suffering can be overcome by elimination of desire. Desire can be eliminated by following the Noble Eightfold Path of moderation and clear thought. She writes that the Buddhist doctrine teaches nonattachment, the sublimation of the ego, that even though there is chaos all around you, you can still maintain detachment and an all-calm inner self, not only freed from worldly attachments to people and things, but also in a state where you really know yourself and are in total contact with yourself. You can achieve this state best, she writes, by the mind-emptying process of meditation so that your mind can open outward to let in life the way a lotus opens to the sun. I don’t understand these commentaries about Buddhism.

My mind feels as scattered as the pieces of a jigsaw puzzle, odd little bits of memory and association waiting to be reassembled within the edges of sky and earth. Lately, I’ve had the recurring fantasy that I am Demeter and Veronica is Persephone. Demeter knew her daughter was lost, and she wandered over the earth searching for her. At first, she simply abandoned herself to her sorrow. Then she consciously entered into it, as though entering a temple, contained in her grief, not only for the loss of her daughter, but also for the loss of the young and carefree part of herself.

WE HAVE FOUND each other quickly, Veronica and I, as if we were the only ones in the airport, embraced each other, kissed, hugged.

Now we sit on the lid of one of my fiberboard cases playing backgammon while we wait for the customs official to finish his examination of my luggage. Veronica is wearing a clean but shabby loose-sleeved, ankle-length white cotton dress and pink plastic Punjabi slippers with toes curled up like handles. She looks transcendently beautiful. A high, straight forehead, glinting cheekbones, straight nose, and a grave, full mouth are a setting for her eyes, which are dark-lashed and forget-me-not blue. Her hair, parted in the center, falls smooth and honey-colored in a long fringed cape around her shoulders. Her fingernails, cut short as they had been when she was a child, have the shimmer of butterfly shells wet from the sea. She is calm, more serene than I remember her.

A few days later, in the morning, outside of Mercara, with the mist rising from the valley and the air chill and foggy, I walk for a while along the road beyond the inn where we are staying, listening to the brook’s rushing susurrus, the burbling of tree frogs giving way to the early morning chorus of birdsong, the fanfaronade of roosters for miles around, and the chime of church bells. I am at once myself in India, and an eight-year-old child walking in Scotland, wondering why the sheep are silent. After our breakfast tea, brought with a pitcher of hot milk topped with a wrinkled skin and a bowl of coarse-grained grayish sugar crystals with a wasp making the rounds of its rim, we set off again in the car, on our way now to Mysore.

Then two Buddhist monks appear, walking ahead of us.

“Tashidelek, tashidelek,” Veronica calls out excitedly, and tells our driver to stop the car.

The monks turn grave, incurious faces toward us. Veronica, with a clear and lilting voice, speaks to them in Tibetan which, as she speaks it, sounds in rhythm and intonation somewhat like Japanese. I hear the wordByllakuppe and Veronica turns to tell me that the monks are on their way there. She asks if we can give them a ride. Of course. Veronica goes on talking with them.

I recall Veronica saying that Tibetans can be too polite. That some kinds of politeness are definitely intended to keep a distance. That sometimes distance is friendly so that a more subtle and low-key communication can take place. That sometimes the distance is intended to alienate because of suspicion, or to start testing. That Tibetans aren’t obsessed by the necessity of keeping up a conversation. That speech should pass through the time-honored Buddhist requirements—is it true? Is it necessary? Will it not be the cause of harm? That being with Tibetans can be quite refreshing, not simply because they’re not hysterical, but because they’re not speedy. That being speedy is a form of aggression. Tibetans aren’t speedy. “That’s what I find anyway,” I hear her say in some past conversation with me, using the same tone she is now using with the monks.

They respond to her in low, resonating voices. Smiles, sweet as a child’s, light up their faces as they move slowly toward the car, wrapped in their voluminous maroon robes. On my mind’s screen, there flashes an image of monks in Bangkok. They are enfolded in robes of tangerine cotton. Frail, wispy creatures, their faces sere, scholarly. These Tibetan monks, like European monks, have a more substantial look. They are large men, so bulky in their robes that I wonder if there is enough room in the back seat of the car for them.

Veronica gets out of the car, opening first one rear door, and then moving to the other side of the car to open the other door so that the monks can each sit beside me if I edge forward on the seat to make room for them. As she presents me to the monks and introduces them to me in such a way as w make it sound as though she were giving them and me a delicious treat. I feel a surge of feeling, a precipitation toward her.

Oh, Elsa Cloud, my darling daughter, my dear, darling angel, Elsa Cloud!

I cross my legs, balancing my ankle on my knee. Veronica immediately hisses at me. “Don’t point your feet at them. Don’t show the soles of your sneakers. They won’t like it.” I quickly place my feet on either side of the drive-shaft ridge.

THE ABBOT of Sera in Byllakupe is interested in what Veronica tells him of her studies in Dharamsala. He would like, he says, to examine her concerning what she has learned about tolerance and compassion. Since they will carry on their dialogue in Tibetan, Veronica and the elderly abbot closet themselves in the reception room, while I wander off in the company of a group of monks of different ages.

Some of them, I am told, are no older than six or seven years of age. For a moment, their maroon robes, their shaved heads, and their solemn mien distort their reality, giving them the look of homunculi, of dwarfs. But no, the moment their teacher’s back is turned, they stare at me with mischievous dark eyes, smiling, giggling and free-spirited, irresistibly lovable because they appear so ready to love, to have fun, to play. One of them runs across the dusty path and up the steps to give me a hug strong enough to last a lifetime, and, embarrassed, runs away again.

A monk in his late twenties, identifying himself as Jhamchoe, tells me by way of explanation for this impulsive show of affection that the child, like himself, had lost both his mother and his sisters, that all of his family had been killed, and that, unlike the other baby monks born in Byllakupe, this was a child who had been chosen to be sent to Byllakupe rather than to one of the Tibetan children’s villages because he was considered to have a special inclination for the spiritual and scholarly life. Smiling a bodhisattva smile that shines impartially on me, he shows me a photograph of one of his uncles wearing the eponymous yellow hat of the Gelugpa order. He tells me that each of the thousand and eighteen woolen threads with which these priestly hats are woven represents a reincarnation of buddhas yet to be born. Some day, he says, he hopes he will pass all the examinations necessary for him to be able to wear such a hat, which symbolizes the full development of wisdom, compassion, and power and the attainment of buddhahood.

Jhamchoe disappears and soon reappears with a basket filled with coarsely crumbled dried milk cheese. Dri (female yak) cheese, he tells me, some of the supply he has carried out with him from Tibet. What a gift to give me! I have no words to thank him. Trying to keep the tears from my eyes, I hug him, embracing him with the same sudden fervor with which the baby monk had hugged me.

Veronica appears at that very moment in the doorway and is suddenly at my side. “Please don’t hug the monks, Mummy,” she says in a fierce whisper. “They won’t like it.”

“It’s all right,” Jhamchoe says, taking my hand. “She is my sister. She is my mother.”

The Abbot of Sera Gompa at Byllakupe gives Veronica and me katas, ceremonial white scarves representing purity of mind and speech, as he and other monks gather on the veranda of the communal hall to see us on our way again. The baby monks, who have been shushed and told to behave by their teachers, and who momentarily stand suitably grave and impassive, twitch irrepressibly into smiles and then shouts oftashidelek, tashidelek, an all-purpose salutation of greeting and farewell that Veronica tells me is untranslatable in English.

I want to tell her not to look so superior, as she says this, but the kata in my hand reproaches me before the words form.

“You asked what a gompa means,” she says, as we drive away, showing off more of her knowledge as she consults a lexicon she has compiled of Tibetan words and phrases. I am being unfair. She really isn’t “showing off.” Resentment when your daughter knows more than you do precedes pride in her accomplishments, I tell myself. I find it hard to accept that there is so much my daughter can teach me, tell me about that I don’t know, and am interested in knowing.

“Gompa means a solitary place, wilderness, a waved leaf fig tree. Hence, a hermitage, so-called on account of its original situation in earlier times, in lonely places abounding in bodhi trees. Later on, these hermitages became converted into monasteries used for the support of monks. So a gompa means a school for reading, writing, debate, prayer, history, logic, philosophy, astronomy, medicine, and so on, as well as a residence for the monks.”

“I liked the monks,” I say. “That’s why I hugged them. That’s why they hugged me.”

Veronica reflects that it seems impossible, but is true, that the love one receives from others comes from one’s own heart, one’s own mind. “Yes,” I say, “there is an old proverb that love begets love.” Veronica is silent. Silence can also be a form of conversation.

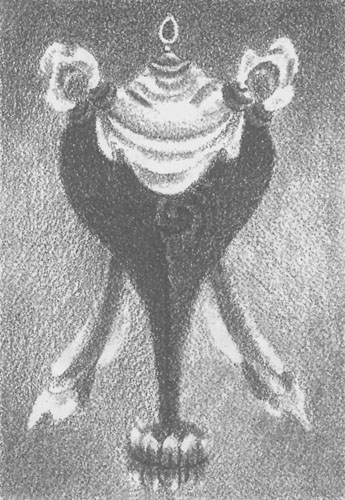

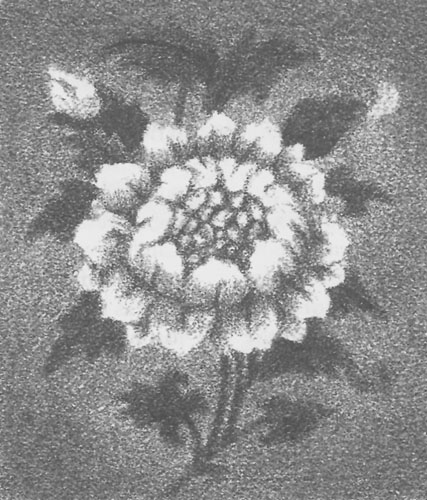

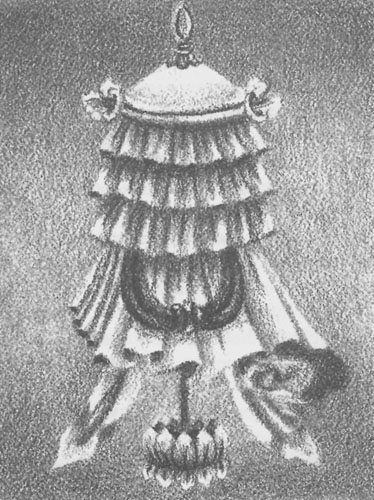

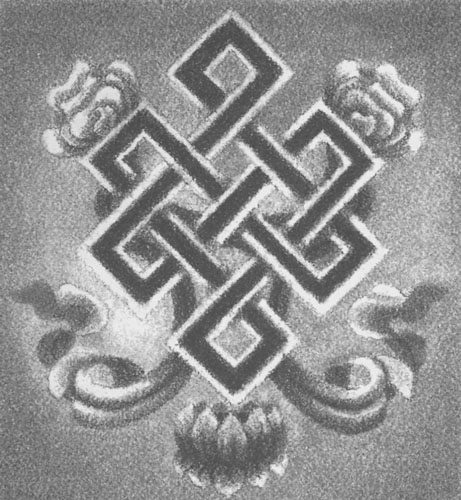

FOR A WHILE, we continue to drive through the estates of Byllakupe, seeing the tilled land, the sleek Swiss cows, prayer flags everywhere printed with script and images of the eight Buddhist symbols of happy augury.

“Here,” Veronica says with tender authority, “let me draw them for you in your notebook.”

Even though the road is not smooth, she draws small, neat, stylized pictures. The covered, lidded vase which holds the elixir of life and symbolizes fulfillment and immortality. The arabesque, or knot, which symbolizes longevity and eternity. The pair of fish, like the yin and yang, symbolizing duality, harmony, fertility. The lotus, blooming from the mud with its beauty, symbolizing purity and compassion. The umbrella of protection. The conch shell, which like a trumpet or a seashell held to the ear, symbolizes the propagation of the dharma. The octagonal wheel of the law, the original symbol of Buddhist teaching. The banner, symbolic of the victory of good over evil.

A few weeks later, linking her arm in mine, Veronica walks with me in Dharamsala up a dusty road with sentinel deodars to the place where the road narrows and becomes the path to the compound of the gompa, the temple, and the residence of the Dalai Lama. In front of the temple there is a platform where monks are seated, chanting to the accompaniment of prayer drums and bells and little horns called gyalings. Over their heads are canopies garlanded with the perpetual knot, the arabesque.

“I love the sound of the monks. They sound like bullfrogs.” Veronica says. Frogs, bringers of rain, bringers of life, worshiped by the Maya. But to me the monks’ chanting, this humming roar, sounds more like the wind, like rocks rumbling, like thunder, an avalanche, a volcano, fumaroles, geysers, waterfalls, like all, yet precisely like none of these, or like parts of all condensed, synthesized. The sound vibrates, pulses, contracts and expands in my mind as though I were part of the systole and diastole of the beginning of creation.

Walking up the stairs behind the canopied platform, we enter into the glow of the temple’s bronze and gilded images, the scented haze of incense and lampsmoke. I feel like a trespasser admitted to a clandestine ceremony, an Orphic, Eleusinian mystery, until I am standing in front of a tented shrine enclosing a mandala made of grains of sand. Looking at the mandala’s patterns of red, green, blue, gold, I feel as one who stands outside a lighted church at night in the lucency of the stained glass, aware of the worshipers within but not one of them. In a niche above the mandala is an image of Padmasambhava, the Indian siddha who came to Tibet.

Veronica greets Geshe-Ia, her teacher, who has appeared with the suddenness of a bird to stand beside us. No, Veronica says, Geshe-la was there all the time. He was standing in the entrance of the gompa and saw us come out of the temple. Veronica says that Geshe-Ia is going over to the residence of His Holiness and that she is going to walk with him to the gate. Would I like to come? And see where the Dalai Lama lives? Is she sure that wouldn’t be an intrusion, an invasion of his privacy? Veronica says Geshe-la wouldn’t suggest such a thing if it weren’t all right.

We follow Geshe-Ia toward an archway with trees and lawns beyond. Through the trees there is a glimpse of a building with a peaked and gabled portico. Two monks are walking along a path leading from the building to the archway. Their saffron undergarments look bright in the sunlight. Their right arms are bare. They walk toward us with the slow, sure, steady pace all monks seem to have here in Dharamsala, a measured way of walking so certain, so smooth that they and we are facing each other through the gate before I realize that the taller of the two monks is looking directly at us, that Geshe-Ia and he are smiling, steepling their hands, bowing their heads in greeting. The taller one passes through the gate to meet us. He has a lovely face, a sweet smile and his eyes are twinkling behind his squarish glasses. Geshe-Ia turns to me and introduces me to His Holiness, the Dalai Lama. My eyes meet his.

Geshe-Ia translates: all religions can learn from each other; the ultimate goal of all religion is to produce better human beings. Better human beings would be more tolerant, more compassionate, less selfish. Love and compassion are the essence of all religions.

“Kindness,” His Holiness says, speaking now in English. “This is something useful in our daily life whether you believe in God or Buddha.” He rests his dark eyes on Veronica and me, and laughs with pleasure, like a child, a wonderful laugh like a billow, like a pillow, joyful, soft, enfolding. He presses his hands together and nods and smiles to Veronica. He holds out his right hand to me and I clasp it with my right hand. “Compassion and love are precious things in life,” he says. “Simple, but difficult to practice.” And then he is gone. I feel free and light, disencumbered. Worry, anxiety, depression have been stripped away to reveal another self—not an entirely new, fresh self, but one that is better, more comfortable. Veronica puts her arm around my shoulder and leans her head toward mine, her ear cupped to my own like a whispering shell.

I DID NOT IMAGINE the church I saw on the road to His Holiness’ residence in McLeod Ganj. Its name is St. John in the Wilderness, and it has been closed for “a long time.” A chaukidar (watchman) who lives across from it has the key. When we arrive at the church, I hoist the stirrup-shaped latch over and back from the gate post, shoulder open the iron gate. Its hinges plaintively mew resistance to trespassers. It is a Presbyterian church. Like the medieval traveler who made a complete circuit of the world without knowing it, I feel I have come back to the place I started from, I have come full-circle. “The wheel had come full-circle. I am here.”

“But how do you know it’s Presbyterian?” Veronica asks.

How could I not know? I grew up seeing small, country churches like these. I spent Sunday mornings in Scotland with my grandmother in a village kirk so much like this one before me that in the quietness, the solitude, my grandmother is here, breathing next to me. The sun dapples the churchyard through the branches of deodars, weaving patterns of sunlight on the grass. I want to embrace this church dedicated to St. John, have the sunlight amber it forever in my mind, this church with its blunt Gothic tower, its dark gray stone durable and grave as the Scottish hills and the Scottish character, which subscribes to illusions of permanence and a stony, exacting morality.

Stained glass in the windows has fallen away from its moldings, been broken, shattered, and only two windows on the lee side of the church remain. In one, two figures, one male, one female, identified with scrolls as Justice and Sacrifice. In the two panels of the other, Jesus and St. John, St. John and a kneeling figure. Their finely etched faces remind me of the paintings of Frederic Leighton, of his Persephone poised before Demeter, who stands in a cave with her arms outstretched. Yes, very Pre-Raphaelite, Veronica says, like Edward Burne-Jones.

The silence is broken by the arrival of the chaukidar and his agitated shrilling. This is a Scottish temple, a Scottish temple, a Scottish temple. We must not go inside unless we take our shoes off. We cannot go inside because he has the key. We cannot go inside because the key he has is broken and is being repaired. Oh woe. In all these years there have been no visitors and now that we are here the key to the door is broken. His wail rises to a high jagged pitch, then lowers slightly as I reach for my purse. An exceptionally large tip produces a pleasing tone, a smile to show that he has put in his false teeth for our benefit. They hurt him and fall out when he eats. Now that he has money, he can buy glue for them, and chappatis and vegetables he can chew. Mayall the gods and the Lord bless us! Ram, Ram!

I listen to his dentured lisp mourning the key, until I can bear it no longer. See? I say. If we just walk to the other side of the church where the windows have lost their glass—shaken loose and broken during earthquakes past—and we pile up these stones, and he is careful not to let them slip, and I am careful to hold tightly to the sill, I can see inside. We won’t need the chabhi, the kungii. All is well. And so it is. Sun through the stained glass panel ofJesus and St. John casts dancing pools of blue and red and gold on the stone floor. Light filtering through holes in the roof illuminates brass oil lamps fixed to stone walls and a bronze eagle gleaming on the lectern. The pews are gone, probably chopped up for firewood long ago, but the bare interior of the church is lovely as it is, with the oil lamps and the bronze eagle of the lectern and a baptismal font its only adornments. The font has an octagonal basin. “Do you remember the little octagonal metal bolt with a brass keyhole glued on top of it that you gave me when you were a little girl?” I ask Veronica. “I loved it so,” I say. When you looked through the keyhole, you could see a scrap of paper on which she had printed “I love you.”

Veronica smiles and nods, and smiling, the chaukidar performs a final mudra. I see him slipping his teeth into his pocket as he goes out the gate. In the back of the church, there is a memorial, and the graveyard to see. The memorial, of gray stone, is all little turreted towers and spires, fenced about with wrought iron and small turreted bollards, a fanciful mix of fortress, cathedral, and castle in miniature. I begin to read the inscription aloud and then stop, and start again, “James Bruce, Earl of Elgin and Kincardine, Viceroy and Governor General of India, Governor of Jamaica, Governor General of Canada, High Commissioner and Ambassador to China, Died at Dharamsala in the Discharge of His Duties on the twentieth of November, 1863. Aged 52 years, four months.”

I recall a drawing ofJames Bruce, eighth Earl of Elgin and the twelfth Earl of Kincardine, which my grandmother had shown me. (“Granny, how could he be two kinds of earls at the same time?” “Because he was, darling. Just look at this superb, almost saintly face.”) Educated at Eton and at Christ Church, Oxford, a contemporary of William Gladstone, he was an intellectual and, according to his biographer, a man of great physical bravery who sat calmly on the deck of a sinking ship during a terrible storm in order to prevent panic among the passengers and crew. “A very brave man, my precious,” Granny said. Granny told me that his mind and faith were ecclesiology, that he was a true Christian, a true man of God, that he had even thought once of entering a monastery. Removing it from a felt bag, unwrapping it from tissue paper, she showed me a silver-backed mirror that had belonged to Veronica, the Countess of Kincardine, his and Boswell’s grandmother. From Boswell, it had passed to his granddaughter who married my great-grandfather who willed it to her. (“Not a mirror, precious, Lady Kincardine’s looking-glass.”)

I reached out my hand to clasp Veronica’s, and with my other hand I touch the name of Elgin on the memorial, my eye’s delight in reading what it knows coupling with the pleasure of a name and the singularity of a life that would endure, as when the name of a place you know is suddenly found on a map or in a book where you would least expect to find it.

Veronica and I walk among dozens of gravestones, some standing, some fallen and moss-covered. “A father deeply and universally regretted,” “a beautiful and beloved child,” “a gentle and beloved wife.” As we rest, standing together in the shadow of the church, Veronica speaks. “Without Buddhism, my life would have no meaning,” she says in a voice as soft and radiant as the gentians and blue poppies growing along the gray stones of the back wall of the church. Then she quotes the Dalai Lama: “Whether one believes in a religion or not, and whether one believes in rebirth or not, there isn’t anyone who doesn’t appreciate compassion, mercy. . . .” Gentle, generous Buddhism. I look at Veronica’s dark-lashed eyes. I look at the glistening Dhauladar above. I look at the Elgin Memorial and the graveyard beyond it. Veronica and I walk together to the edge of the spur. Far below, fields stretch toward the mountains of the horizon. There is the road like a winding lane leading up to Dharamsala and its patchwork of rust-red roofs, roofs the color of plums, the flesh of pomegranates. Dharamsala, a resting place.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.