Mae Chee Kaew was a Thai villager who overcame enormous obstacles to leave home and follow the Buddha’s path, and went on to be recognized as one of the few known female arahants of the modern era. As Bhikkhu Silaratano recounts in Mae Chee Kaew: Her Journey to Spiritual Awakening and Enlightenment, before she died in 1991 at the age of 90, Mae Chee Kaew had the good fortune to meet Thailand’s most renowned 20th-century meditation masters. Here, in a brief biography adapted from his book, Bhikkhu Silaratano traces Mae Chee Kaew’s determination to ordain and to cultivate a mind of clear awareness.

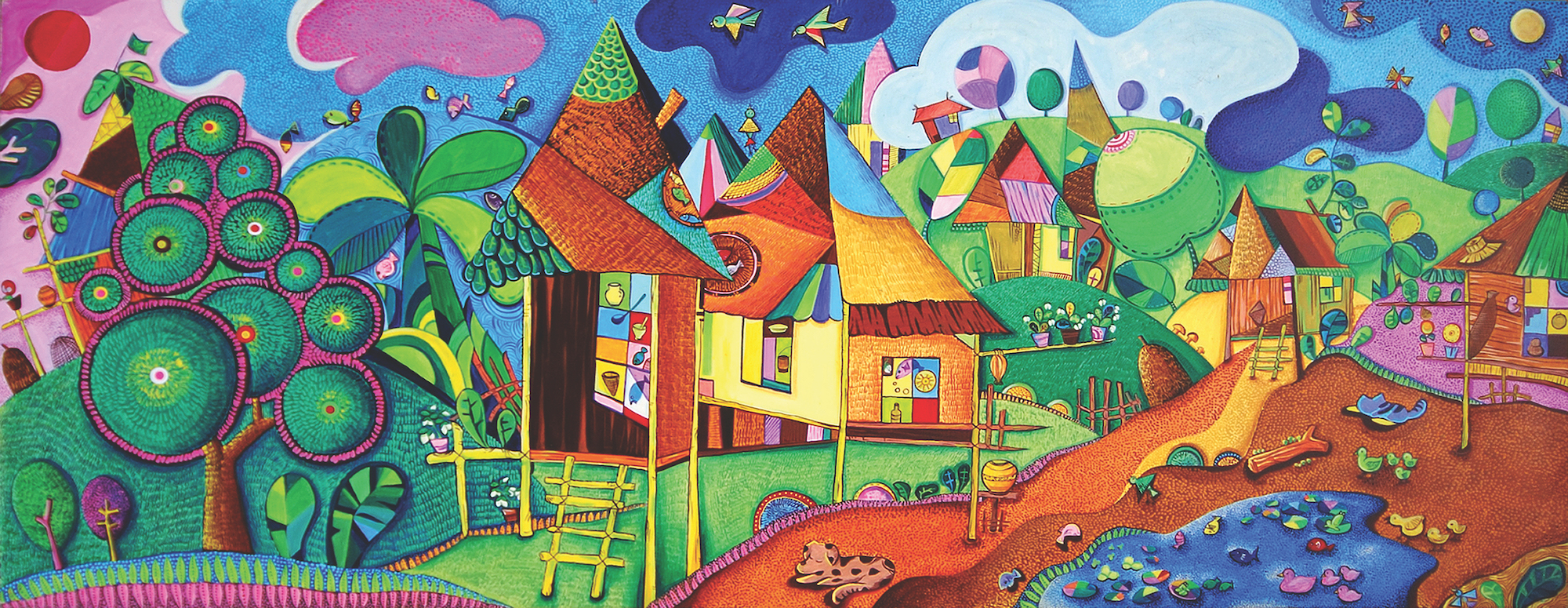

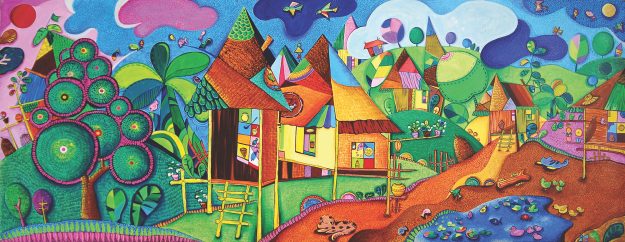

From time to time in the dry and hot seasons of the year, wandering forest monks passed through Mae Chee Kaew’s farming village, Baan Huay Sai, searching for places to camp and meditate in solitude. The mountains and forests surrounding the village were areas of vast wilderness, forbidding and inhospitable, where wild animals roamed freely and malevolent spirits were said to hold sway. Out of fear, the villagers stayed away, making it an ideal place for the monks to practice their ascetic way of life in seclusion.

In 1914, the arrival of Ajaan Sao Kantasilo—a renowned master in the Thai forest tradition—transformed the spiritual landscape of Baan Huay Sai forever. Crossing the Mekong River from Laos, Ajaan Sao led a small band of disciples through the tropical heat and arduous terrain, reaching the vicinity of Baan Huay Sai just as the annual rains were beginning. Following the Buddha’s instructions, forest monks cease wandering and reside in one location for three months of intensive meditation during the monsoon season.

Ajaan Sao entered Baan Huay Sai one humid, misty dawn, leading a column of monks in ochre-colored robes. Barefoot, with alms bowls slung across their shoulders, the monks made their way through the village to receive whatever generosity the inhabitants had to offer: rice, pickled fish, bananas, smiles, respectful bows. Stirred by the monks’ serene, dignified appearance, the residents of Baan Huay Sai scrambled to make offerings to them. By the time Ajaan Sao and his monks walked past Mae Chee Kaew’s childhood home, her whole family was standing expectantly on the dirt track out front, waiting to place morsels of food in the monks’ bowls in the hope of accumulating special merit.

Eager to discover the identity of the new arrivals, Mae Chee Kaew’s father and a few friends followed the monks to their temporary campsite in the nearby foothills. Although Ajaan Sao was venerated as a supreme master throughout the region, the villagers had never met him face to face. Surprise turned to joy and excitement when they discovered who he was. Mae Chee Kaew’s father resolved to make sure that Ajaan Sao settled in the area, if only for the duration of the monsoon season. He guided the venerable master through the local terrain of fast-flowing streams and winding rivers, overhanging caves and rocky outcrops, open savannah and dense jungle, proposing various retreat sites. He was overjoyed when Ajaan Sao chose an area of flat sandstone boulders near Banklang Cave, only about an hour’s walk from the village.

Once the monks were settled, Ajaan Sao gave teachings to the villagers. To instill faith, he encouraged them to replace the custom of sacrificial offerings to local spirits with the practice of taking refuge in the Buddha, Dhamma, and Sangha. To inspire virtue, he encouraged them to observe the five moral precepts for lay practitioners, refraining from killing, stealing, lying, committing adultery, and taking intoxicants. To help them overcome fear of the local deities, Ajaan Sao taught them the protective power of meditation. First, he guided them in paying homage to the Buddha by chanting the Blessed One’s virtues. Then, once their hearts were calm and clear, he taught them to repeat the mantra buddho, buddho, buddho.

As custom dictated, the villagers reserved part of each monthly lunar observance day for religious activities, visiting the monks to offer food, help with the chores, listen to teachings, and practice meditation. Mae Chee Kaew, then 13 years old and still known by her childhood name, Tapai, often accompanied her parents on early morning hikes to the Banklang Cave. Being a girl, she was not allowed to mingle with the monks. So, when Ajaan Sao spoke to his lay supporters, Tapai sat at the back of the assembly behind the older women, just within earshot of his soft, mellow voice. Peering over her stepmother’s shoulder, Tapai drank in the atmosphere and the teachings. Ajaan Sao’s down-to-earth manner, serene temperament, and dignified appearance inspired deep devotion in the young girl. Even though she did not make an effort to meditate as Ajaan Sao instructed, Tapai sensed in her heart that he had attained perfect peace. Without being fully aware of it, she was being pulled in a new direction by the force of his personality.

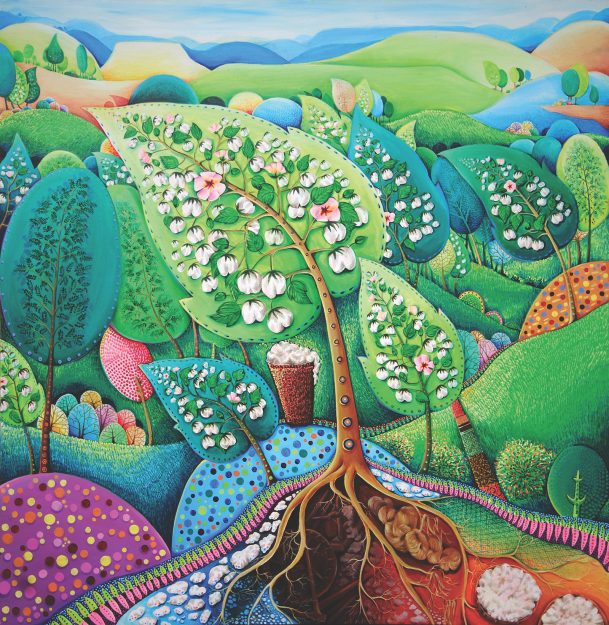

Tapai first felt this tug on one memorable occasion. Ajaan Sao was praising the local womenfolk for their generous support, assuring them that their daily offerings were not only beneficial to the monks but also a blessing for their own future well-being. Still, he added, the virtue of generosity was nothing compared to the virtue of renunciation practiced by white-robed nuns meditating in the forest, cultivating a fertile field of merit for all living beings. His remarks stirred Tapai at the core of her being, planting a seed in the young girl’s heart that would one day grow into a venerable bodhi tree.

Ajaan Sao spent three years living in the vicinity of Baan Huay Sai, first in one forest location, then in another. Tapai’s father was sad when Ajaan Sao eventually departed, but he was consoled by the knowledge that Buddhism was now firmly established in the hearts and minds of his Phu Tai neighbors. Little did he suspect, though, that Ajaan Sao’s departure would be succeeded by the arrival of the most revered Buddhist master of them all, Ajaan Mun Bhuridatto.

In 1917, as the annual monsoon season was fast approaching, Ajaan Mun and a group of sixty monks reached the wooded foothills overlooking Baan Huay Sai. They camped under trees, in caves, under overhanging cliffs, and in nearby charnel grounds. Following Ajaan Sao’s groundbreaking path into the community, Ajaan Mun’s arrival caused great excitement.

Mornings, as Tapai placed food in Ajaan Mun’s alms bowl, he frequently spoke to her, encouraging her to come and see him. Feeling shy, she dared to go only on special religious days when she was with her parents and other villagers. Ajaan Mun was always exceptionally kind to her. Knowing intuitively that she possessed uncommon spiritual potential and deep devotion, he began encouraging her to practice meditation. He explained the same basic technique that Ajaan Sao had taught: to silently repeat the word buddho until it became the sole object of her awareness.

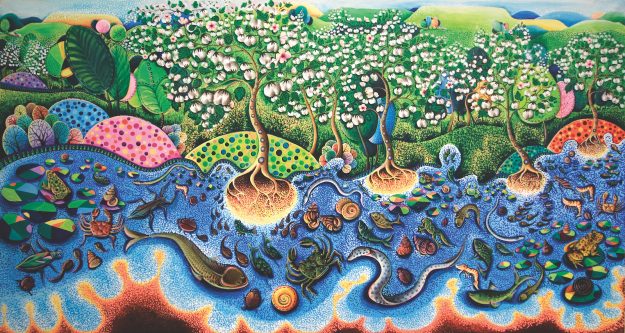

One evening, Tapai sat down and began reciting the buddho meditation, and after 15 minutes her mind reached a profound state of stillness. She suddenly saw a vision of her own body lying dead in front of her—an image so vivid that it convinced her she must have died. She watched as Ajaan Mun walked solemnly toward her corpse, then tapped it three times with his walking stick, declaring with each tap that the body is impermanent, that it does not last, but that the heart is never born and therefore does not die when the body dies.

With each tap of Ajaan Mun’s stick, Tapai’s body decomposed further, until only the bones remained. From the skeleton, Ajaan plucked what appeared to be a seed from her heart center and held it in his palm. Tapai spent the entire night seated in meditation, completely absorbed in the vision of her dead body. Only at the first light of dawn did her mind withdraw from deep samadhi.

For the next three months Tapai applied herself wholeheartedly to meditation. With Ajaan Mun’s wise counsel, her practice developed quickly. When she began telling him of her unusual experiences during meditation, the monks quickly gathered around to listen, eager to hear her stories about the nonphysical realms of existence, as well as Ajaan Mun’s instructions.

One day, shortly after the rains retreat ended, Ajaan Mun sent for Tapai. He explained that he and his monks would soon be leaving the district. He asked if she had a boyfriend, and when she said no, suggested that she ordain as a white-robed renunciant and follow him on his travels. Stunned at his suggestion, Tapai said that she wanted to accompany him but was afraid her father would never allow it. With a reassuring smile, Ajaan Mun sent her home to ask.

As Tapai had feared, her father refused to grant her permission to ordain. He was concerned that should she later disrobe and return to lay life, she would have difficulty finding a husband. He urged her to enjoy a normal life and be satisfied with her lay religious practice.

When Ajaan Mun heard that, he encouraged Tapai to be patient. When the time was right, he said, she would have another opportunity to develop her meditation skills. Another qualified teacher would come to guide her. Meanwhile, she must stop practicing meditation and be content to live a worldly life. Ajaan Mun saw that Tapai’s mind was extremely active and that she did not yet have sufficient mental focus to meditate safely on her own. Should something untoward arise during her meditation, she would have no one to help her in his absence.

Tapai did not understand Ajaan Mun’s reasons for forbidding her to meditate, but she had enormous faith in him. So she abruptly stopped practicing, even though she felt her heart would break.

After Ajaan Mun’s departure, Tapai became quiet and withdrawn. The joy and excitement that had pervaded her life disappeared when she stopped meditating. Shy by nature, Tapai was not motivated to socialize and instead threw herself into work. She planted cotton that she picked, combed, and spun into dense thread. She spent hours at her loom, weaving fabric that she cut and sewed into looped skirts and loose-fitting blouses. She cultivated indigo trees, extracting dark blue pigment to dye the fabric. She raised silkworms, spinning the raw silk into thread that she wove into coarse garments.

Tapai’s multiple talents and other prized traits—stamina, dependability, loyalty to family, respect for her elders—made her exceptionally desirable for marriage. Before long, suitors appeared. One in particular, a neighborhood boy named Bunmaa, made a proposal to her parents. Still deeply moved by Ajaan Mun’s teaching, Tapai showed no interest in romance or marriage. But when her parents consented to Bunmaa’s proposal, she obeyed their wishes. Marriage was part of the worldly life Ajaan Mun had said she must be content to live for the time being.

Once married, Tapai dutifully attended to the wifely chores expected of her, but she felt constricted: the small, tight corners of her marriage hemmed her in on all sides. Every year was a repetition of the same tedium, the same suffering. Only 17 years old when she married, before she knew it, she was 27. She began to think more and more about leaving the world behind and assuming the uncomplicated life of a Buddhist nun. Quietly, her determination grew. Finally, one evening, she knelt beside her husband and tried to make him understand how she felt, how she wanted to be relieved of her domestic duties so she could renounce the world and ordain. Her husband’s response was cold and uncompromising: he flatly refused to discuss the matter.

Tapai knelt beside her husband and tried to make him understand how she wanted to be relieved of her domestic duties so she could renounce the world and ordain: he flatly refused to discuss the matter.

Tapai’s marriage had been childless, and her family began to worry about who would look after her when she grew old. So when one of her cousins, who had many children, became pregnant again, it was decided that the baby should be given to Tapai to bring up as her own. Tapai named the girl “Kaew,” her “little darling,” and when people noticed her devotion to the child, they began calling her “Mae Kaew,” or “Kaew’s mother.”

Raising a daughter was a joyous experience for Mae Kaew, distracting her from the tedium of her life. But she never abandoned her true aspiration. She often visualized herself joining the nuns at Wat Nong Nong, shaving her head, wearing plain white garments, living in silence, and meditating again. But with a daughter to raise, the possibility of ordaining seemed more remote than ever.

Still, Mae Kaew tried to convince her husband to allow her at least a short visit to the monastery, but he continually refused. Finally, an elderly uncle, respected and admired by all for his wisdom and fairness, was asked to mediate. He had known Mae Kaew since she was a young girl and sympathized with her aspiration. Speaking privately with Bunmaa, he extolled the virtues of religious practice and urged him to be fair to his wife. A compromise was reached: Bunmaa would allow Mae Kaew to ordain for the three-month rains retreat—but not a day longer.

Mae Kaew was delighted. Ajaan Mun’s 20-year-old prediction was finally coming true. She vowed to make the most of her time as a nun. After so many past disappointments, she would not disappoint herself.

On a cloudless day in July, at the age of 36, Mae Kaew knelt before the monks and nuns at Wat Nong Nong and left behind everything that embodied her former life, everything she considered herself to be, to become a mae chee, a rightfully ordained Buddhist nun. On the morning of her initiation, Mae Kaew arrived at the monastery early, joining the other nuns for an austere meal. Then, one by one, the distinguishing marks of her old identity were stripped away. Butterflies fluttered in her stomach as the head nun, Mae Chee Dang, chopped off her long black hair until only bristly stubble remained. Looking at the hair piled around her feet, Mae Kaew reflected on the illusory nature of the human body: Hair is merely a part of the natural physical universe. It is in no way essential to who I am.

After Mae Chee Dang shaved the dark stubble off Mae Kaew’s head, the other nuns dressed her in the traditional bleached-white robes of a mae chee: wraparound skirt; loose-fitting, long-sleeve blouse buttoned at the neck; and a length of cloth tucked under the right armpit and draped over the left shoulder in a characteristic Buddhist gesture of reverence.

After 20 years of an unsatisfying marriage, a door finally opened for Mae Chee Kaew, and she stepped through, entering a life of renunciation. Intending to honor her marriage commitment, she returned home at the end of the rains retreat, but in her absence, her husband had developed a drinking problem and had begun an affair. After three months in the supportive community of nuns, Mae Chee realized that she would never find happiness trying to repair her family. Making the hard decision to leave her eight-year-old daughter behind, she returned to the monastery.

Mae Chee Kaew’s career as a nun flourished. In 1945 she founded a monastic community for women in Baan Huay Sai. Ajaan Mun’s prophecy that a qualified teacher would come to guide her came true when she met Ajaan Maha Boowa in 1950. Striving diligently under his guidance, Mae Chee Kaew never wavered in her determination to attain enlightenment. She contemplated the body until all doubt was eliminated; then her focus shifted to investigating the mind. Living quietly in her forest retreat, Mae Chee Kaew strove night and day to penetrate the truth about the radiance of her mind until, in a single brilliant moment, the radiance dissolved and her pure essence merged into the boundless ocean of nibbana.

One of the few known female arahants—fully enlightened beings—of the modern era, Mae Chee Kaew was living testimony that the Buddha’s goal of supreme awakening is possible for everyone, regardless of gender, race, or class.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.