The monastic community’s commitment to spiritual practice provides a model of the awakening life. For this reason, it’s natural that lay practitioners often feel reverence for them. Out of this admiration, however, can arise a misunderstanding—that only nuns and monks are capable of real progress on the path. But the Karmashataka Sutra, also known as The Hundred Deeds Sutra, paints a very different picture. It shows us that spiritual realization is not solely the province of monastics. In the stories of this sutra, monastics and lay practitioners advance toward awakening together.

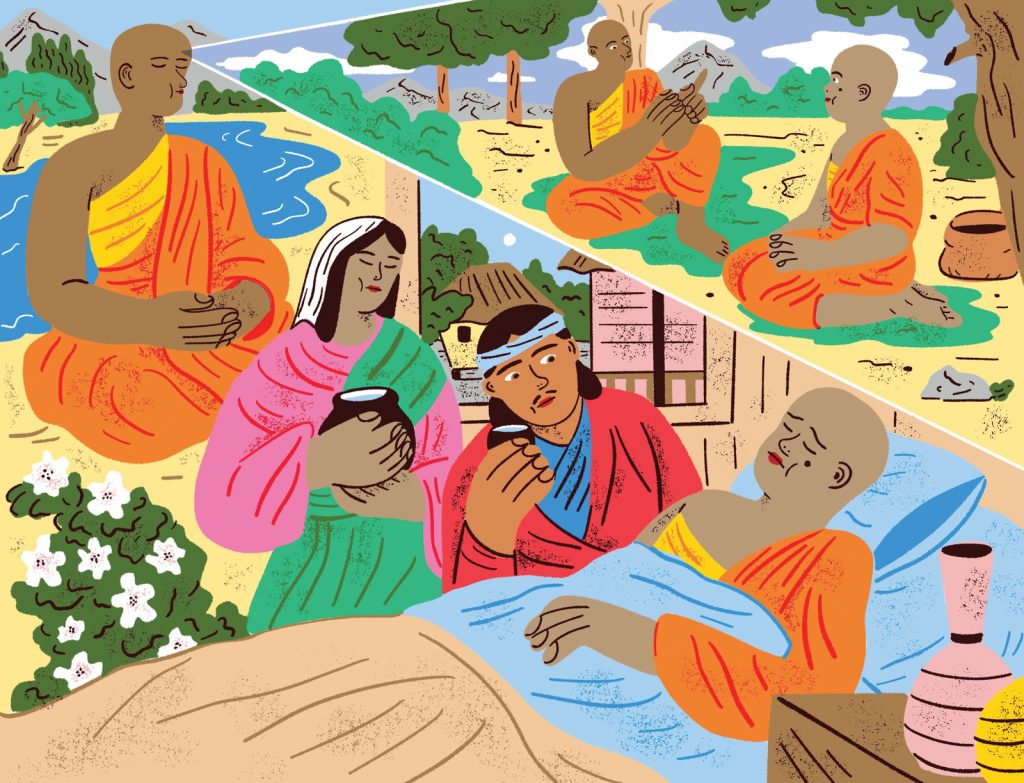

Many of these narratives, called avadanas, depict ordinary people welcoming the Buddha or his disciples to their homes for the midday meal. Afterward, the most senior sangha member offers a teaching. Hearing the dharma from an ordained person provides a great spiritual inspiration for the characters in the sutra, just as it can today.

One of the stories of the Karmashataka particularly demonstrates the deep connection between the monastic and lay communities. “The Story of Purana” tells of a young person who enters monastic life but whose realization, when it happens, takes place not in the monastery but back at home. Moreover, when he does awaken, every member of the household shares the benefits.

The story opens during the Buddha’s stay in the ancient Indian city of Shravasti. It features Venerable Aniruddha, one of the Buddha’s foremost disciples. Among his many students was a householder who was very receptive to the teachings.

[Ven. Aniruddha] led the householder to remain steadfast in perfect faith, to take refuge, and to maintain the fundamental precepts. He inspired him to give gifts and to share what he had, and in no time at all his home became like an open well for those in need.

At the time, the householder and his wife were eagerly awaiting the birth of their son. The couple hoped that the child would eventually carry on the father’s work, provide care when the parents grew old, and make offerings after their death to help create the conditions for their favorable rebirth. The parents did not know that Ven. Aniruddha had clairvoyant vision: he knew that the baby had been a highly realized being in his previous life and was now taking final rebirth before attaining enlightenment.

Purana’s realization takes place not in the monastery but back at home. When he does awaken, every member of the household shares the benefits.

One day, the monk arrived at their home unattended by any other monastics. “Noble one,” the householder asked him, “why have you come here alone, without companions or attendants? Noble one, is there no one at all who could attend you?”

“Where shall we find attendants,” Ven. Aniruddha replied, “if one such as yourself does not grant them to us?” The householder resolved then and there that the child they awaited would be placed under Ven. Aniruddha’s care to be trained as a monk.

The child was born, and they named him Purana. In due time, Purana happily became Aniruddha’s attendant and achieved full ordination. At the monastery he practiced “earnestly, forgoing sleep from dusk till dawn.” But despite his efforts Purana was unable to achieve realization before he fell gravely ill and had to cut short his studies. Though he remained ordained, he returned home to be cared for by his parents.

Purana’s commitment to spiritual practice turned what could have been viewed as a cruel twist of fate into a kind of blessing. He used his illness as the basis for a spiritual breakthrough. Working with his painful disillusionment, Purana achieved true renunciation of samsara. He became an arhat, free from afflictive emotions.

Purana did not keep his understanding of the dharma to himself. He shared what he knew with his parents and the members of their household, tailoring the teaching to suit each of them perfectly. This led them to realizations of their own. What happened is described in a vivid passage that recurs throughout the Sanskrit canon—more than fifty times in the Karmashataka alone—whenever householders or others truly enter the process of awakening:

The householders and their retinue destroyed with the thunderbolt of wisdom the twenty high peaks of the mountain of views concerning the transitory collection and manifested the resultant state of stream entry right where they sat.

In other words, the force of their new understanding shattered their towering misconceptions of how life is supposed to be, and thus their son’s teaching launched them irrevocably toward awakening.

As it turned out, Purana’s teaching of the dharma was his parting gift, for the illness took his life. At his memorial service, the Karmashataka tells us, the Buddha gave “a discourse on impermanence to all the four retinues”—that is, to the monks, the nuns, and male and female lay practitioners. He did not single out a particular group among them but demonstrated equal concern for the entire community by offering a teaching appropriate to all. Together, they mourned the loss of the young monk and felt the Buddha’s words guide them along the path.

In the “Story of Purana” we see that lay support is essential to the continuation of the monastic tradition. The sangha depends on a robust community of householders for its very membership. They also depend on the generosity of lay students in the traditional forms of food, clothing, medicines, and other needs. While most of us are not likely to have the experience of offering up a child to be our dharma teacher’s personal attendant as Purana’s parents did, these material gifts may be within reach.

Of course, this support goes both ways. Householders in their pursuit of enlightenment depend on the monastic learning of their teachers. In pursuing merit, the laity also relies on the sanctity of those teachers’ vows, which makes them worthy of reverence.

In the end, the monastic and lay communities are not just mutually dependent but mutually sustaining.

This truth runs far deeper than the material level—a point that was made directly to one of the authors of this article. Kaia once remarked to their teacher, Gen Lozang Jamspal, that they appreciated his skill and value. The teacher did not hesitate to offer a correction.

With just four words, he cut to the heart of the matter.

“No student? No teacher.”

♦

This is the third installment in a four-part series on the Karmashataka (“The Hundred Deeds”) Sutra, a collection of ancient teaching stories on karma that has recently been translated from Tibetan into English. Read the first installation here and the second installation here.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.