In his book The Snow Leopard, Peter Matthiessen chronicled his journey to the Tibetan kingdom of Dolpo in northwest Nepal. At that time, he learned of the even more inaccessible Kingdom of Lo, which dates back to the Middle Ages and is better known to Westerners as Mustang. Last May, Matthiessen reached this remote Buddhist land by horseback, in company with photographer Thomas Laird, a resident of Kathmandu. In this extract from his journals, Matthiessen describes the Masked Lama Dances of the Tiji ceremony, an annual three-day reenactment of a myth reflecting this mountain desert’s dependence on scarce water as well as the Buddhist teachings on impermanence.

Lo is bordered on three sides by Tibet, from which its culture and language are mostly derived. Until this year, travel in Lo has been discouraged by Nepal—especially after 1959, when it became the base of operations for the Kham-ba guerrillas from Eastern Tibet who resisted the Chinese occupation. The kingdom was entirely closed to visitors from the early sixties to late 1991, when a new government took over in Kathmandu.

To the outside world, Lo is better known as Mustang, a corruption of the name of its main fort city, Lo Monthang, which in its great days in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries dominated trans-Himalayan trade. Soon thereafter Lo’s decline began, partly because of the exhaustion of the dry environment, but also because of the constant warfare between the feudal states of the Himalayas. In the seventeenth century, Lo was forced to pay levies to a new kingdom, Nepal, but did so without relinquishing its ancient feudal system of kings and serfs. And while serfdom was abolished in 1956, Lo continues to maintain a king, as well as a certain loose autonomy within Nepal.

Some years ago, the royal couple, King Jigme Palbar and his wife Rani Sahib, lost their only child, a boy of eight. The Queen has borne no other children, but the King will not take another wife to produce an heir. “I brought her so far from her home,” he once told Tom Laird, “and she would hurt so.” Eventually the crown will pass to his brother’s son, the Crown Prince Jigme Singbe Pal bar Bista, who lives in Kathmandu but has come here for Tiji, a festival of renewal held every spring.

With the Crown Prince are four Europeans, business associates, it appears. (The Crown Prince is said to have interests in the Tibetan rug industry—New Zealand wool, European capital, peasant weavers—that has replaced tourism as Nepal’s foremost industry and is rapidly despoiling the fragile ecology of the Kathmandu Valley, bringing not only overpopulation and child labor but ruination of the precious water by dyes and chemicals.) These four, along with three French photographers and a Japanese TV crew, all of whom arrived today, are the only foreigners in Lo Monthang besides myself and Laird, who believes we will be the first outsiders ever to witness the legendary Masked Lama Dances.

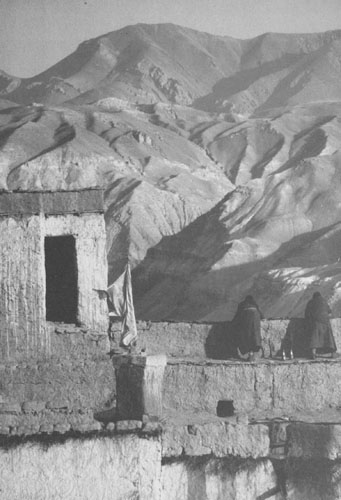

Prayer flags fly everywhere in Lo Monthang, and every roof is stacked with brushwood, used to kindle cooking fires in the mud stoves (the sole fuel at this altitude is dung); it has been interesting to note the change in the composition of this wood as we rode northward through the wild country east of the Kali Gandaki river. In Jomsom, which lies close to the fir forests, there are woodpiles of small logs, in Tange there are limbs, whereas here in this high desert it is meager thorn bush, scoured from the stony mountainsides above. Poplar and willow saplings are nursed in small stonewalled enclosures near the towns, but like the new limbs on the cropped cottonwoods, they are much too precious to be used as fuel and are saved for construction purposes, mostly ceilings and roof beams. The kingdom’s subsistence economy is based on trade in agricultural and animal products.

Barley and buckwheat, cultivated by methods at least a thousand years old, are the grains that fare best at these altitudes, where a short growing season and a dearth of water, arable land, and fertilizer severely limit growth. Like most of the towns above ten thousand feet, Lo Monthang is limited to one crop each year-the one favored here is mixed wheat and peas-with a little mustard greens as vegetable. Bread and farina, with hard cheese and endless cups of butter and tea, are the foundation of the Tibetan Buddhist diet, but meat and fat are eaten too, mostly in stews.

The Tiji Ceremony began on the twenty-ninth of May in the main square east of the palace, under snappeting prayer flags, white cracked walls, and blueframed windows. On the palace’s second-floor balcony, glowering down upon the celebrants, is a huge old mastiff, traditionally accoutred in red ruff (another mastiff, this one stuffed, hangs like a mobile from the ceiling on the second landing). Early in the afternoon, horns resounded through the town—first the short horn, or kagyling, which announces the two twelve-foot copper dunchens, with their elephantine blartings, and then the two double-reeded horns (the player is trained to blow two horns through one mouthpiece with a peculiar technique of double-breathing), all accompanied by drums and cymbals. The striking gold-green-redblue spiral painted in the center of the drum represents “the ceaseless becoming of Mind,” an ancient symbol that accounts in part for the regional fascination with the salegram, a black river stone containing a spiral fonn of a marine fossil.

Next, an ancient and enormous tanka (thangka, a scroll painting) three stories high is unrolled down the entire south wall of the square. The tanka portrays Padmasambhava (or “Guru Rinpoche”), who brought this ceremony to Tibet in the eighth century (it is said to have originated in Afghanistan) and founded the Nyingrna sect of Tibetan Buddhism. Following an incense purification, the healer-lama and religious painter Tashi Chusang, accompanied by Crown Prince Jigme in black fur hat, black leather boots, and tailored traditional dress, makes an offering of six brass bowls of grain; these are set on a wooden altar with the painted butter cakes made from farina that we had seen fashioned the day before by a group of monks in a chapel of the palace.

At midafternoon, in high wind and blowing dust, eleven lamas in maroon and gold, wearing high red hats, come from the palace and take their places along the wall beneath the tanka with the silver-haired high lama, Tashi Tenzing, on the elevated seat just in the center. At one end of the line, two monks commence a sonorous overture on the twelve-foot horns, which are supported at the farther end by a carved wooden stand. Horns and drums are accompanied by cymbals struck more or less casually by the line of lamas—except for Tashi Tenzing, who in his gentle, unobtrusive way appears to do everything with complete attention, and not only with attention but with quiet celebration of every moment of his life.

As the monks and lamas commence chanting, twelve more monks come from the palace in maroon and royal blue and glittering gold brocade, topped by cymbal-shaped hats decked with upright peacock plumes. Soon they withdraw and are replaced by the masked dancers who introduce the Tiji myth explained to us yesterday by Tashi Tenzing at the New Monastery.

The myth is a long one, taking three days to enact, but, briefly, it concerns a deity named Dorje Jono who is fated to save his people from the scourge of his own father, a terrible demon who has wreaked havoc on the land, bringing about a shortage of the precious water, causing their animals to miscarry, and creating all manner of disasters that threaten famine—or even an end to their society. (A dearth of water is the greatest ill that can possibly befall this culture and has already befallen it, in a centuries-old shift of the Kali Gandaki river that caused the abandonment of the original fort-castle of Kechar Dzong—now a stranded ruin on a desert hill above the town—and has never been forgotten to this day). Dorje Jono repels the demon through the power of his magical dancing—he dances fifty-two separate dances, one of them in ten different bodies, each with a different head-during the course of which he finds time to poke fun at the clownish figures of a Hindu yogin and a Chinese Ch’an (Zen) master. As the dances end, Dorje Jono kills the demon, after which his people are relieved of their plague of misfortunes, water becomes plentiful, and the balance and harmony of existence are restored. Thus, Tiji (from tenche—the hope of Buddha dharma prevailing in all worlds’—”not just Lo,” Lama Tashi says, “but Germany! Everywhere!”) is effectively a spring renewal festival, acting out the cultural myth that is based, like all else, on precious water, the source of which is now confined to a small and solitary glacier that may be seen high in the west.

King Jigme, who adjudicates his people’s problems, says that all they ever talk about is horses and water. Recently, a woman was fined five hundred rupees (about ten dollars, a very large sum by local standards) for carelessly misdirecting one of the small irrigation channels, which are controlled by small mud dams opened and closed by hand. The rupees were distributed to the people whose fields had been deprived.

Because Tiji days seem to start in the afternoon, we are free to make excursions in the morning. One day we visit the great red Champa LhaKang, a temple dedicated to the future Buddha, whose enormous clay figure behind the altar soars toward the ceiling and disappears downward into the darkness of a closed floor below.

Champa’s upper wall is supported by wood columns perhaps eighteen inches in diameter, or very much larger than any tree now to be found in the parched kingdom. The columns are constructed out of sections like big upright logs that one can imagine (one to a side) on the backs of yaks, toiling and blowing up the Kali Gandaki from the forests on the south side of the Himalaya. All around the altar room are magnificent frescoes, and the mandala on the rear wall to the left of the Great Buddha figure is, in the opinion of Tom Laird—a scholar of Buddhist art—a true masterpiece of line and detail, color and floral patterns. On this one he discovered a signed inscription: “I have come from Kathmandu to paint this picture,” and Laird believes that the other mandalas, which are fine indeed but not of this luminous quality, were done by disciples under this man’s supervision. The mandalas represent many years of painstaking work in what must have been near-darkness, and went largely unseen for many centuries until the scholar Giuseppe Tucci arrived here in the early fifties. Tucci predicted that these wonderful old temples, Champa and Thukche, would scarcely survive his own departure; and it is true that they cry out for repair before they perish, as did a third temple, Samdruling, a few hours distant, which was still standing as late as 1963.

At Thukche Lha-Kang, the altar room is 115 feet long by 65 feet wide and 30 feet high, or as large as those in all but a few Tibetan temples. Unlike Champa, it has an ancient aka floor—not mud as in the other buildings, but a kind of worked pebble cement. Its columns are square instead of round, and a row of sharptoothed wooden lions circles the central light-well. (These lions are also present in Jo-Khang temple in Lhasa, the greatest attraction in the Tibetan capital besides the Potala Palace of the Dalai Lamas.) Though the walls are of mud brick (five feet thick in places), the wooden doors and columns, as well as Champa’s giant Maitreya Buddha, convey the massiveness of the great wooden Buddhist temples that were built originally in India and may be seen to this day in Japan.

For the second day of Tiji, numbers of Loba (people of Lo) have arrived from the outlying hamlets, and the small square is thronged with wild, beautiful people, with all of the women and children, at least, in traditional dress. The crowd is cheerful and unnaturally clean, though plenty of dirty ones turn up to maintain the old standards, and a few, entirely drunk on chang (fermented barley beer), lie in wood doorways. On the south wall the great ancient tanka has been replaced by one no more than a century old, Laird thinks, a tapestry of fine embroidered silk brocade brought by the King’s father from Lhasa.

Again today, the ceremonies do not start until early afternoon, by which time the great wind out of India has catapulted a huge dust storm onto the plain. No doubt the tardiness accommodates the newcomers, some of whom have traveled a considerable distance. I spent the first part of the day far up the mountainside, tracing the braided irrigation channels all the way back up through the willow plots and stone-walled fields to the clear brook that comes down from the glacier, and by the time I descend the mountainside to Lo Monthang and join the madding crowd in the palace square, the dark winds and monsoon clouds I have fled for the last hour are upon us. However, the crowd is not dismayed by the dust whipped into its round faces, and joyfully laughs and whistles at the antics of the clowns, two diminutive masked monks less than ten years old.

With the bright masks and many colored costumes, the hard mountain light, the log-laddered earthen dwellings with their flat roofs crowded by strong brown, blackbraided Asiatic faces, the scene is strongly reminiscent of the kachina dances of the Hopi and Pueblo peoples of the American Southwest, where in recent years Hopi spiritual leaders and Tibetan lamas have been discussing all sorts of ancient correspondences between their peoples.

Eventually, the King appears in turquoise-green wool boots and a regal purple robe, and with him is Rani Sahib, also in purple, wearing a whole crown of tiny river pearls set off by dozens of large red coralline stones interspersed with matched ornaments of turquoise. The Crown Prince, too, wears purple, as well as a shirt of fire-gold over neat Western trousers and black leather boots. All are attended by royal relatives, the men in peaked hats of gold brocade, the women in imperial displays of turquoise and silver.

Trailing after the royal party are the camera-laden Gennan and Norwegian businessmen, decked out in parodies of local dress, gold hats perched high on their long Western heads (the embarrassed young woman in the party has had sense enough to refuse the funny hat). At one point, the King’s sister is moved out of her chair and the German moved into it so that he may appear on Japanese TV with the royal party. All of these odd figures, between masked dances, present themselves before Lama Tashi Tenzing, who drapes each craned neck with a white silk kata (a ceremonial scarf) or red ribbon. Even the TV crew whose camera and sound boom, wrapped in gleaming plastic against the dust, have been obtrusive in the ceremony ever since their three-thousand-dollar-per-hour helicopter shattered the sun- and mountain-silences on the first morning, are given katas by the lama, and are thoroughly photographed by one another in the process.

It would be easier to deplore the eager Westerners and bustling Japanese seeking to give pennanence to this ancient celebration of impermanence were we not among the miscreants ourselves. Fortunately we are few in all, and are mostly lost in the horde of undefended merry faces. The costumes and masks, the twelve-foot horns, the gold cups of wheat, the butter cakes, the snow peaks and wind and dust and sun, the snow leopard, snow pigeons, salegrams, the dying glacier and the desert ruins, the drunks and kings and foreigners and dogs and yaks—all Tantra!

This morning we returned to Champa for another look at the wonderful mandalas and, while we were there, measured the room and the fifty-foot-tall Maitreya figure, which until a few years ago was the largest Buddha figure in Nepal. I lit five butter lamps to the future Buddha, made my alien bows, and said goodbye.

From Champa we proceeded to the palace, where the King was holding informal court for visiting dignitaries and lamas. He was seated in front of the west window, silhouetted by the bright reflections from the snow peaks behind.

As in medieval courts, the assemblage was serenaded by a damyin, or Tibetan guitar, to which a rickety old man began to dance and sing, smiling as crazily as a court jester. Then a solemn young boy took over on thedamyin, and two men danced, seriously now, and the boy danced, too, even as he played. The old Tibetan song they sang honors the King: On the golden ridge we raise the golden flag. . .

Going out, the King invites Laird and me to the palace for the midday meal, which is presided over by Rani Sahib. We dine on an excellent rice-and-onion dish with pickled radishes, noodles with three different species of wild mushrooms, potatoes, and mustard greens.

Outside the room, the courtiers are preparing ancient Tibetan muskets—blunderbusses, really, since the muzzles are flared wide like horns—to be used to finish off the Demon in this afternoon’s grand finale to the Tiji ceremony. The muskets are rigged with two bayonetlike spikes that swing down from the muzzle to support the front end (the nomads use paired antelope horns), to increase the chances of striking the infernal target.

Toward the end of yesterday’s ceremonies, after the royal party had departed, the masked dancers, clad in animal masks—mastiff, raven, snow leopard, red deer, and other beasts less easily identified—joined forces to attack the Demon, who had been reduced mysteriously by his hard circumstances to a cloth doll perhaps two feet long. Into this figure was thrust, in an intenninable ceremony, a series of blue daggers, until, just at dark, the Demon’s pitiful remains were borne away into the palace, and the line of cold windswept lamas under the huge tanka became free to leave. Departing the courtyard, Lama Tashi Tenzing, still attentive and still smiling, touched the foreheads of the little children who ran forward to be blessed, even while the great tanka was pulled away from the wall so that all present would walk beneath and touch their heads to it and receive Guru Rinpoche’s universal blessing.

On the third day, Tiji ends with the ceremonial destruction of the evil remains, represented by some long black yak hair and red torma cakes (ceremonial images made from flour and water) minced to a dark red gurry. The remains are chanted over by a lama, as his assistants burn juniper and frankincense, and two lines of monks strike hand drums while those against the wall blow horns. Eventually, a procession forms, led by three victory banners, red and white, then the bearers of five braziers containing the Demon’s remains, then the horn blowers and monks, then lamas, then court musicians, then the King and the Crown Prince and their attendants. The procession pauses for chanting and ceremony at the chortens outside of the main gate, then repeats the ceremonials at the grain-threshing platforms east of the walls, arriving finally at the edge of the town fields.

It is near twilight, a wild mountain light, and on the wind, just beginning to diminish as the cold night falls, white clouds filled with western sun drift past the snow peaks, as snow pigeons wheel over the new green of the spring fields. In the cold light, on the sere sky, Kechar Dzong and its ruined terraces are as pale as Egypt.

The Demon’s red remnants are set out on an old tiger skin, whereupon they are attacked by bow and arrow, slings, and the old guns. One by one, the braziers filled with the poor devil’s remains are overturned upon the ground, each time to a wild cannonade from the old muzzle-loaders and a wave of cheers and smoke. Finally, the emptied braziers are removed and the sad remains flailed with the tiger skin, to satisfy the crowd that nothing has been overlooked in dispelling the forces of evil from the town.

Tiji is over, and tomorrow the people will go home to their own villages. We, too, shall depart, following the west mountain-wall of Lo south to the Himalaya. I circumambulate the town for the last time, in cold clear light.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.