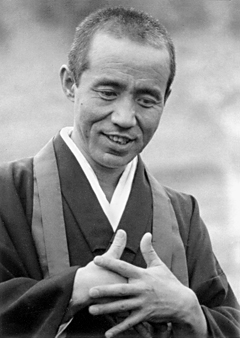

Kobun Chino Roshi (1938—2002)

Kobun Chino Otogawa Roshi, Zen teacher and holder of the World Wisdom Chair at Naropa University, died in a drowning accident in Switzerland on July 26 while he was attempting to rescue his five-year-old daughter, Maya, who also died. He was sixty-four years old.

The last of the original Soto Zen teachers who established practice centers on the West Coast in the 1950s and 60s, he was known for his clarity of presence, approachability and kindness, and his insistence that students rely on their own authority in spiritual practice. Kobun Chino Otogawa, better known as “Kobun Chino,” arrived in America from Eiheiji Monastery in 1967 to serve as resident priest at the San Francisco Zen Center’s “Haiku Zendo” in Los Altos, California. Suzuki Roshi moved him almost immediately to oversee practice at Tassajara Zen Mountain Center, the first Buddhist monastery founded in the West.

“I don’t think people realize how important he was in establishing Tassajara,” says Bob Watkins, who studied with Kobun Chino for thirty-five years. “There were only a handful of us there at the time, sitting on army blankets in the old building we used as a zendo. In the beginning Kobun taught us everything—how to put the zendo together, breathing, posture, how to do oryoki meals in navy surplus bowls.”

Born into a family of priests in Niigata Prefecture, Kobun Chino received a Master’s degree in Mahayana Buddhism from Kyoto University in 1965 and trained at Eiheiji Monastery. He was skilled in the Zen arts of calligraphy and archery, and was often asked to assist at other American centers because of his deep knowledge of Buddhist ceremony. “He gave himself completely,” remembers Watkins, “never asking for credit, and not accepting credit.”

Although Kobun Chino went on to found centers in California, New Mexico, and Austria, he always shunned the limelight, preferring to be called simply “Kobun,” and allowing his students to address him as “Roshi” only in recent years. His teaching style was informal, unpredictable, and sometimes elusive. The first time I arrived for sesshin at Hokoji Zendo in New Mexico, I inquired whether the teacher had arrived yet. “He may come and he may not come,” the monk who greeted me shrugged. “Anyway, it’s all about the sitting, isn’t it?”

“He was forever ungraspable,” recalls one longtime student. “He refused to let us give away our authority over our own practice. ‘Just sit,’ he’d tell us, ‘and everything else will come.’”

“He didn’t want to get into politics and hierarchy,” remembers another. “He wanted us to be free and independent. He wanted us to be American Buddhists.”

One of the last times I saw Kobun Chino I asked if he might do an interview for a book I was writing on American Zen. He was silent for a moment.

“Tell them we know nothing of Zen,” he said. “Tell them we only know just sitting.” He smiled. “Tell them that.”

Funeral services were held for Kobun Chino and Maya Otogawa on July 30 in Engelberg, Switzerland, at the home of his senior dharma heir, Vanja Palmers. He is survived by his wife, Katrin, and their son and daughter, Alyosha and Tatsuko, as well as two adult children, Taido and Yoshiko.

—SEAN MURPHY

The Gentlest Hands: Remembering Kobun Chino

My first taste of Zen—in 1972—came at Philip Kapleau’s center in Rochester, New York, when I was a college student. The combined effects of simplicity and polish in the zendo—along with the distinct Japanese love for wood and straw—made a deep impression. But I found the Rinzai-inflected Dharma Hall somewhat intimidating. I didn’t understand the shaved heads, or that strange figure who stalked the hall with a sinister wood staff for smacking the upper back of a drowsy student. The Roshi himself seemed an imposing figure, and zazen a grueling discipline.

After I’d relocated to Santa Cruz and a year or two had passed, I discovered the breezy little zendo in that coastal town. It was one of a tight group of clapboard houses on the bluff, next to the old Spanish mission’s armory. Ramshackle in a California way, the porch sloping and its paint scaling, the meditation hall still had a fresh, airy feel. The tatami mats smelled delicious. In those days, Kobun Chino would drive over the Coast range mountains Tuesday evenings from his Los Altos center to meet with the colorful Santa Cruz outfit. Kobun usually arrived during zazen, slipped in the door, and when meditation was over was seated in his robes on a little dais at one end of the room.

My first Tuesday in the zendo, as I faced the wall, struggling to watch my breath, hoping to “get” what this meditation thing was, I felt a cool influx of air. The door had opened. No sound of feet, only a brushing movement (the swish of black robes), and a moment later the gentlest hands I’d ever felt were on my spine and shoulder, carefully adjusting my posture. That was all. Unseen hands saying to the new student, Try it this way, it might work better.

“Dharma gates are numberless, I vow to enter them,” runs part of the zendo chant. Looking back, I realize that that touch, the fact of those hands, was the gateway into dharma for me. I’d read some sutras, but without that senseless display of kindness, who knows how much Zen would have stuck? A tiny moment, but indicative of Kobun’s instinctive map of the zendo and his instinct for tenderness. What better commentary could one imagine for all those baffling Zen cases? Direct transmission of mind outside the texts, indeed!

And so it is that this practitioner of small accomplishment must now give three bows to the dharma-gate hands of Kobun Chino Otogawa Roshi, who drowned on July 26 along with his daughter, Maya.

The night before Kobun’s death, a companion and I were walking the open space by Boulder Creek. Across a clearing, huge wings lowered into a cottonwood—she saw it—a barn owl. It gave a wild rasp—then another—and continued to screech until we’d gone out of earshot. Peterson’s describes the sound: “a shrill, rasping hiss or snore.” Sibley’s says, “a long, hissing shriek.”

I can’t remember which culture thinks the screech of an owl precedes the death of someone close. Probably it’s just superstition—that a nonhuman culture can presage an event—and Zen would shrug it off as it does “wild fox barking” in Japan. But then a barn owl has the most elaborately designed ears. There is a region in the owl’s brain with specialized cells that pick up the coordinates of every sound and constructs a minutely accurate map of auditory space. Did you know that’s how an owl hunts in the dark? The gateway between its mind and the dark meadow is completely open.

Why does this seem so much like the lore of Zen? Asking over and over: What’s inside, what’s out?

Waning ocher moon,

owl light & one bright screech

settle into

the creekside branches.

What does it mean, Roshi?

Whose dark wings are those in the West?

A few foolish students ask

But you have taken the owl tooth under your robe

Taken our questions

& gone among

peaks—

cloud after cloud after cloud. ▼

—ANDREW SCHELLING

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.