After completing You Want It Darker, his final studio album, Jikan Leonard Cohen recorded the vocal tracks for a handful of new songs. Four years later, in 2019, his son, Adam, released them with full instrumentation on Jikan’s posthumous album, Thanks for the Dance. I’d been waiting for this one. Though he had never spoken to me of these songs, I knew a few of the things that had been on his mind when he was working on at least one of them.

I think of Leonard Cohen’s career as having three stages. The raw, tears-of-blood troubadour of “Chelsea Hotel,” usurped by the knowing middle-aged cynic-prophet of “The Future,” who gave way to the wise old Yiddish Yoda of “Going Home.”

It’s stunning when you think about it. How many artists live long, mellow out, wise up, get over themselves, settle into their liver-spotted sheaths, and sing coded spiritual messages and love songs to God, whispered flirtations with the ineffable about loneliness, acedia, lust, hope, true love, and the first and fourth noble truths in Buddhism—that life is shot through with both suffering and the possibility of transcendence?

Three hours after its release, Thanks for the Dance was widely available on YouTube. (“Eighty percent of my music is consumed mostly for free on the internet,” Jikan once glumly remarked to me.) I put on my cracked and superglued Sony headphones. It was about noon. I was taking a break from a novel I was writing that incorporated Zen themes into a pretty bonkers dystopic setting.

I have to be careful when listening to Jikan. An avalanche of memories always trembles behind his bass-baritone voice, waiting to be triggered. It didn’t take long for him to whisper right into my ear from the grave. The first track on the album, “Happens to the Heart,” contained what could only be a passage about our mutual Zen teacher, Joshu Sasaki Roshi.

In 2012, a former monk wrote an article about Sasaki Roshi accusing him of a decades-long pattern of sexual misconduct. It was titled “Everybody Knows.” This was a reference, of course, to Jikan’s famous song about the political corruption and spiritual rot that we know but never name, which flourishes all around us “From the bloody cross on top of Calgary / to the beach of Malibu.”

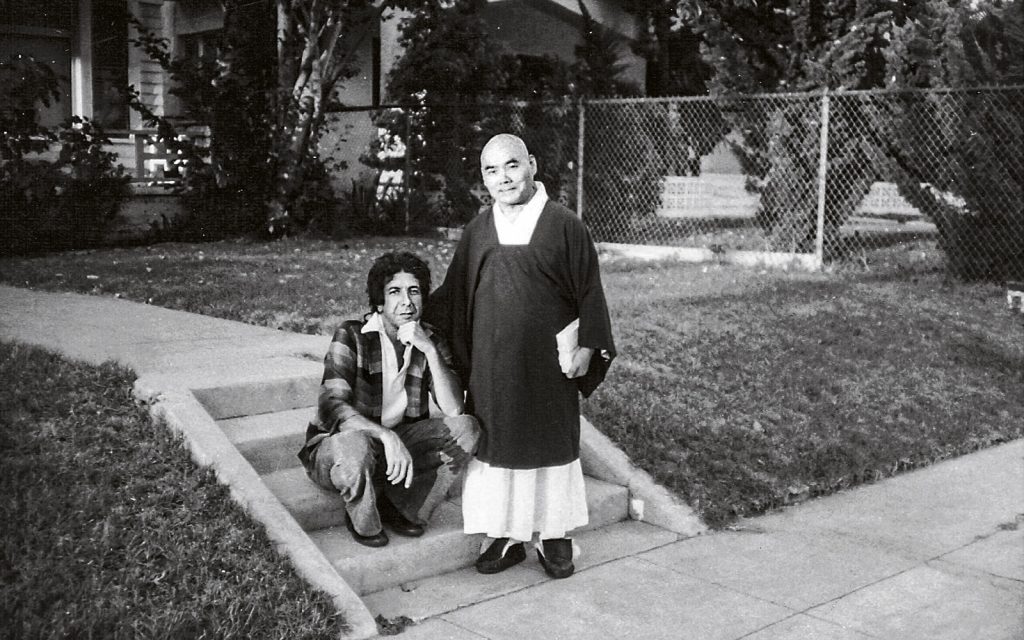

A week after that article appeared online, Jikan brought dinner from Greenblatt’s Deli to our Zen temple in LA. Eight months earlier, Roshi had suffered a near-fatal bout of aspiration pneumonia. He was 106 years old. He rarely left his second-story apartment overlooking the plum tree in the inner courtyard.

Roshi, his Inji/attendant Soshin, Jikan, Jikan’s assistant, Aysun, and I ate our chicken soup and beef tongue in silence. Then Aysun and Soshin went for a massage at a Koreatown spa, Jikan’s treat. Roshi fell asleep in his chair, and Jikan and I had some time alone to talk.

In 1996, Roshi ordained Leonard Cohen as a lay Zen monk. It didn’t stick. He bolted from the monastery and went to India to study with Ramesh Balsekar, a onetime translator for the legendary Advaita Vedanta master Sri Nisargadatta Maharaj. Then, one day, I looked up from my meditation cushion and there he was, old Jikan bowing and entering the zendo in his threadbare monk’s robes. He had tea with Roshi that evening.

Roshi didn’t have friends; he had students. Jikan, though, was somewhere in between a friend and a student. The morning we rushed Roshi to the hospital for aspiration pneumonia, Jikan was the first person Soshin phoned.

“Why Leonard?” I asked her in the ICU as Roshi coughed up day-old nori seaweed from his lungs.

“Leonard opens doors,” she said.

Indeed.

He secured for Roshi the private room at Cedars-Sinai usually reserved for senators and Oscar winners. When Roshi returned from the hospital to our LA temple, Jikan’s Beverly Hills doctor paid regular house visits. Jikan became a fixture in Roshi’s personal quarters, and, with his help, Roshi recovered just in time for the sex scandal to break.

Jikan and I cleaned up the leftover chicken soup as Roshi slumbered on his faux-leather chair. I unknotted Roshi’s bib, and Jikan hand-washed it in the bathroom sink. We sat on the carpet at Roshi’s feet. It was November, but Soshin kept the apartment hot enough to puddle the stick of butter in its dish on the kitchen counter. Jikan removed his double-breasted pinstripe suit jacket.

Over the previous eight months Jikan and I had shared many moments like this. Quiet afternoons where he sat cross-legged on Roshi’s couch, tweaking lyrics or searching for inspiration on his iPad (obscure blues songs or Federico García Lorca poems—sometimes a YouTube midrash by a hermetic rabbi he knew). We talked about the “new atheists” (he didn’t like them) over pickled plums and gyokuro tea, watched Grand Sumo matches on NHK World-Japan, and changed our teacher’s soiled incontinence pads.

“People think poetry is this exalted thing,” he told me one day. He shook his head. “You’re a plumber, on your knees, making sure the pipes fit so the shit flows smoothly.”

I think Jikan had come to a point in life where he’d realized that all work, be it poetry or plumbing, was more or less the same. The important thing was not what kind of work you did but whether your work was honest. If it was, it spoke for itself. Fittingly, Leonard’s ordination name, Jikan, means “noble silence.”

An artist can’t strive to make art any more than a monk can strive for enlightenment.

At the time, I thought of Jikan as a great writer and a mediocre monk. He seemed to have given up on the quest for enlightenment and was content to bask in Roshi’s presence like a bhakti yoga devotee. Yet his sincerity and good humor humbled me. I trusted him.

“What’s the news?” he said, as I massaged Roshi’s feet.

“Not good.”

More women were coming forward to share their stories. Two former Zen students had just published accounts online of how Roshi had made unwanted advances toward them in the late 1970s.

“It’s a reckoning,” Jikan said.

The humidifier and all six heaters were on full blast. The room was soggy and boiling like a butterfly house. I tiptoed to the windows overlooking the plum tree and let in some air. As I returned from the window, Jikan held out a glass of cognac.

“What are you writing these days?”

If he was trying to shift the conversation away from Roshi’s scandal, it didn’t work. “An apology letter,” I said.

His hands were folded in his lap, and his thin legs were crossed in full lotus. His head was slightly cocked, and he was looking into my eyes. Jikan’s face tended to match his music. You couldn’t tell what he was thinking, but you could feel it.

“Somebody ought to write a novel about this stuff,” he said, after a pause. I think he sensed that I was stuck.

Then he gave me some material to work with. It was about the old days. All-night drunken dance parties in the zendo meditation hall after sesshin retreats; monks and nuns sleeping with each other, and each other’s boyfriends and wives; hippies going to formal interviews with Roshi high on acid. One such hippie allegedly charged Roshi with every intention of attacking him. The gesture was returned in kind. He wound up in Roshi’s lap with his robes pulled up, his underwear pulled down, and Roshi smacking his ass with a wooden hossu stick, the two of them laughing hysterically.

“Different times,” Jikan said, glancing up as Roshi softly breathed.

He told me the story of how Roshi’s eccentric wife had tried to sue one of his students, a writer who was also Jikan’s friend. Jikan wound up footing the legal bills for both parties, all the while hiding this fact from each of them.

Jikan didn’t mind sharing stories that cast him in a negative light, including one about when he was a young writer with an inflated ego. That afternoon he was holding court before a clutch of Zen students. “At one point I looked around the dining hall. I was searching for the right word.” His eyes stopped at the head of the table. Roshi was staring down a row of students, right at him, like a bull about to gore a matador.

“I could feel his total contempt for me. You arrogant son of a bitch. Who do you think you’re fooling?”

We were interrupted when my phone lit up with a text. I was in one of those hell realms unique to our age where you or someone you know is in the middle of being “canceled” and every ping of an arriving electronic communication stops your heart. The news media, I had concluded, are like a Mythical Creature—as much a product of our times as a record of them—that goes about slaying other people as you watch through your telescope from a healthy distance. Then, one unlucky day, you see the Creature sniff the air, turn its head, and lock eyes with you.

Worse than the daily tsunami of phone calls and emails from reporters who wanted to know, as a Los Angeles Times writer put it, why I was harboring a sexual criminal, were the emails, texts, and phone calls from enraged sangha members who wanted to know why, as one Zen student put it in an email dispatched from her deathbed, I wasn’t “protecting Roshi from this goddamn lynch mob.”

This time, though, it was just Soshin saying she and Aysun were going out for Turkish coffee. With a sigh of relief, I powered down my phone.

Battle lines were being drawn in our community. In the following weeks I would finish writing the apology letter to the women who had been harmed by our community. I believed in the letter, believed in it the way a Christian Scientist believes in prayer. I believed that the right words properly chosen could heal. And this letter spoke to the absolute worst of our behavior over the years—the denial, the neglect, the prevarication; it was, in an era of hollow apologies, a genuine one. The letter was then signed and made public by our Zen priests.

Soon after, that Mythical Creature, assuming that the wrongdoings that we had openly acknowledged were merely the tip of the iceberg, reared its head. It was open season, starting with a hit piece in the New York Times.

Those in our community who had not signed the apology letter, who were not priests and did not hold the same weight as priests, felt that we had misspoken for them and betrayed our teacher. They never forgave us. Meanwhile, the other half of our sangha felt that the apology letter did little to properly clean out the wounds gouged by Roshi’s sexual misconduct.

It was time to put Roshi to bed. Jikan took one arm, and I took the other. We led him past the shoji screen and lowered him onto the indentations waiting for him in his memory foam mattress. We rubbed Eucerin lotion on his skeletal calves and poured a cocktail of vitamins through the plastic G-tube in his side.

Then we sat on the couch in relative dark and total silence. I stared down at the moonlit pavers in the courtyard, anticipating Soshin and Aysun’s return.

Jikan had special status within our community. He was Roshi’s buddy, his most famous student, our dharma brother and poet laureate. He could back both sides in a legal argument with a writer friend and his teacher’s wife; he could express support for those calling for reform within our sangha as well as those circling the wagons around Roshi. He got a pass. He did not have to choose sides. I both resented and respected him for this.

Jikan looked up from the plum tree he had helped to plant in the courtyard decades ago. “Don’t ever repeat this,” he said.

He told me one final story for the night.

And I’m looking in his eyes. And I’m thinking, Leonard. I’m a writer. I’m a personal essayist, for God’s sake. You know I’m going to use this. And he’s looking back at me. And he knows what I’m thinking. But he goes right on telling me his story, in an almost ritualistic manner, as though he is giving it to me. Handing it over. Entrusting me with the goods.

“What is going on here?” I wonder. “What is this generosity about?”

Looking back now on all the stories Jikan shared with me that evening, I can see a pattern of dark and light, of enlightenment and abuse, in our teacher, our community, our tradition. I was waiting for Jikan to make a statement about that pattern. But perhaps the pattern itself was the statement, the way he wove it together. “Somebody ought to write a novel about this stuff,” he had said. But maybe he wasn’t telling me what to write about but how to write, and how to think and live as a writer and an artist—and maybe even as a monk. Be careful when trying to make things right with words, he might have said. Perhaps that is not their job.

You arrogant son of a bitch. Who do you think you’re fooling?

Just fit the pipes together and let the shit flow.

Seven years after that evening with Jikan, I sat down to listen to “Happens to the Heart.” Midway through, he sings:

Then I studied with this beggar

He was filthy, he was scarred

By the claws of many women

He had failed to disregard

No fable here, no lesson

No singing meadowlark

Just a filthy beggar guessing

What happens to the heart.

Fucking Jikan.

I couldn’t listen to the rest of the album. I couldn’t finish working on my dystopic Zen-infused novel either. I just sat in my apartment and thought of the final story Jikan had told me that night, and how he had reshaped that story, I felt, and all of the stories he had told me that night, in his poignant stanza in “Happens to the Heart.” Eight lines, forty-one words. In them, echoes of every argument I’d ever heard for or against our teacher and so many others like him in American Buddhism.

This is how you do it, I thought at my desk.

Great writing suggests, it doesn’t decide. It opens up the problem, it doesn’t solve it. Great writing speaks for itself while the author maintains noble silence.

Jikan’s face tended to match his music. You couldn’t tell what he was thinking, but you could feel it.

A week after our evening together, Jikan returned to Roshi’s apartment with more Jewish food. We unpacked the bags in the kitchen. When Soshin left to grab soy sauce from downstairs, he turned to me.

“What are you working on?”

“Just another grab bag of Zen pieces,” I mumbled. He had written the foreword for my first collection of essays, Zen Confidential: Confessions of a Wayward Monk.

He paused. His expression shifted. I could feel what he was thinking. In that moment I had the courage to wonder if there wasn’t a different path available to me as a monk and a writer than the one I was on.

I don’t remember exactly what he said next. It was something like, “I could feel a certain yearning or striving for artistry in your first book. Certain moments where you hit the mark too.”

What did he mean? That I’d hit the mark in a few spots but failed overall? That I had promise? That my overall project did not permit for true artistry, what with its author being tethered to the propagandistic role of “Zen” writer?

It was a ten-second conversation in the midst of a busy day where I had monastic responsibilities that included trying to navigate the scandal-punctured sinking ship of our head temple. You would think that that moment would have been lost in time. . . .

Yet there I sat at my desk seven years later, replaying it in my head along with all that had happened since. For one thing, I was no longer a full-time monk. After Roshi died, I wrote about the events around his sexual misconduct in my second book. This infuriated those in my sangha who had a different interpretation of the Buddhist precept of right speech than I did. I realized I could not write and say what I wished to and remain at the head of our organization. I resigned my role as the administrative abbot at the home temple, became what I’ve come to think of as a “spiritual free agent,” and began work on a novel. Not the novel Jikan had suggested, but not not that novel, either.

Hands folded on my desk, his voice rumbling through my headphones, I remembered that special period in my life when I had undertaken, unbeknownst to me at the time, a kind of soft apprenticeship under this extraordinary artist. Great writer, but a mediocre monk, I had once concluded about Jikan. Now, I wondered. Maybe one didn’t have to choose between these two paths. Maybe they complemented each other. To be an artist or a monk, or both, requires a sacrifice of ego; an aversion to bullshit; an enhanced resilience to discomfort, penury, and loneliness; the courage to practice right speech; and the wisdom to know when and where and how to maintain noble silence.

Most of all, though, an artist can’t strive to make art any more than a monk can strive for enlightenment. The important thing is to do honest work and leave the rest to fate, the muse, the dharma. You can’t control the outcome. You can’t make things right. Whether you’re a poet, a priest, or a plumber all you can do is give yourself completely to the work.

Let it speak for itself.

In “Going Home,” one of his best late-career songs, God (I assume) gives this Leonard Cohen character some writing advice.

I want him to be certain

That he doesn’t have a burden

That he doesn’t need a vision

That he only has permission

To do my instant bidding

Which is to say what I have told him to repeat.

Amen.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.